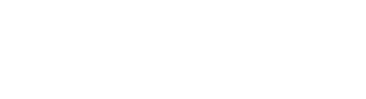

Texas Health Presbyterian Hospital in Dallas on the evening of Wednesday, Oct. 1, 2014. (Jim Tuttle/The Dallas Morning News)

Texas Health Presbyterian Hospital in Dallas on the evening of Wednesday, Oct. 1, 2014. (Jim Tuttle/The Dallas Morning News)

Learning From Ebola Mistakes, North Texas Hospitals Make Changes

A year after Ebola arrived in Dallas, it might seem like hospitals and clinics are back to normal – except for the leftover hand sanitizer pumps and the occasional sign warning about international travel. But, underneath the surface, there are larger shifts in health care in how nurses and doctors work together, and how hospitals are preparing for whatever is the next Ebola.

Let’s start where Ebola began in the U.S. — the room at Texas Health Presbyterian’s emergency department where Thomas Eric Duncan lay sick with Ebola.

Even though it’s been one year since Duncan was in this room, the stigma is so strong the hospital doesn’t want to reveal the room number.

Once again, in the tug of war between fear and science, emotion pulls harder.

Dr. Daniel Varga, chief clinical officer at Texas Health Resources, said even though staff was aware of Ebola in 2014, no one thought it would happen in Dallas.

“We believe we were very well attuned to the potential risk of Ebola, and that we had communicated that fairly aggressively,” Varga said. “What we didn’t do is train and simulate for that.”

Dr. Daniel Varga is chief clinical officer at Texas Health Resources. Photo/Lauren Silverman

Now the hospital is emphasizing training to prevent confusion. For example, when the state of Texas issued new guidelines on how to put on and take off personal protective gear, administrators didn’t just hand out an instruction sheet for nurses to read in their free time.

“We’re actually training people in donning and doffing the garment,” Varga said. “That’s a major change for us in terms of how things were set up a year ago.”

That sounds small. But remember that the tiniest mistake while removing those protective suits can mean coming down with Ebola.

That’s the theory behind what happened to Presbyterian nurses Nina Pham and Amber Vinson.

What happened at Presbyterian

Communication on policies and procedures, as well as among staff, was one of the critical flaws cited by an independent panel that reviewed what went wrong at Texas Health Presbyterian Hospital.

In response, nurses, doctors and scribes who take notes now work in “pods” or teams. All wear a small black device with a grey button around their neck.

Nurse Misty Cogburn uses it to find a colleague. Doctors who used to see 55 patients at a time are now treating a dozen, she said.

Misty Cogburn is an emergency department nurse manager at Texas Health Presbyterian Hospital in Dallas. Photo/Lauren Silverman

“The physician, the nurse and the scribe will come together and do the discharge together so they can ask any additional questions,” Cogburn says. “The whole team is involved.”

That’s to help prevent mistakes like the one with Thomas Eric Duncan. He was sent home after his first ER visit. Although Duncan, who had a fever above 100 degrees, did tell a nurse he had recently traveled from Africa, that information wasn’t verbally communicated to the doctor.

Here’s the thing: Even if the physician didn’t know Duncan’s travel history, there was another red flag that should have kept the doctor from sending him home. It’s called a SIRS, or sepsis score, and it essentially measures when a patient is likely to develop a life-threatening complication from an infection.

“When the SIRS score for Mr. Duncan got to 3 or higher and was highlighted in red, the reassessment that we would hoped would have happened, to go back and find out why has Mr. Duncan’s SIRS score gone to 3 or 4, and what should we do before we send him home, didn’t happen,” said Dr. Jeffrey Canose, chief operating officer at Texas Health Resources.

Today, if a patient hits a high score, it triggers multiple alerts and staffers know to respond, Canose says.

An employee at the emergency department at Parkland Hospital. The hospital remains on alert for Ebola, an official says. Photo/Lauren Silverman

After Ebola, many lessons learned

So far, all the lessons learned are meant to help identify people with Ebola, not treat them.

That’s because — in perhaps the biggest change from last year — Presbyterian, or any other hospital in North Texas, won’t be treating Ebola patients.

“While I think the care of an Ebola patient is well within the scope, there’s such an overwhelming impact to the rest of operations and the safety of patients and caregivers that cohorting them makes the most sense,” Varga said.

The federal government has identified 55 hospitals to transfer people with emerging infectious diseases like Ebola — including two in Texas. Right now, those places are the University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston and Texas Children’s Hospital in Houston.

There could be another Ebola treatment center established in North Texas. A location hasn’t been chosen, but the new $1.3 billion Parkland Hospital has been tossed around as an idea.

Parkland Hospital in Dallas. Photo Credit/Parkland

Dr. Alexander Eastman is chief of the trauma center at Dallas County’s public hospital. He’s responsible for disaster preparedness. He says Parkland is still on high alert, asking every new patient about travel history to screen for infectious diseases.

“Whether it be Ebola or now we’re working on looking at some of the others that are out there to date, we’ve screened almost 1.5 million people,” Eastman said. “I know it’s enough to keep people from slipping through the cracks. It’s about whether the screening tool is used effectively and of course it requires the patient to be honest and to disclose that they have potentially been somewhere, which is an important factor.”

And out of the million-plus people Parkland has screened, some have come up positive, but none turned out to have Ebola. Getting results for a blood test though is much faster and easier than it was last year. Today, samples are examined in Dallas instead of having to be sent to Austin.

And minutes matter when it comes to infectious diseases like Ebola. To cut down on treatment time, John Peter Smith Hospital in Fort Worth has supply carts ready to roll if a patient screens positive for an infectious disease.

“We can pull a room together in a moment’s notice should we have a patient show up in our ED,” said Wanda Peebles, chief nursing officer at JPS.

Dr. Kent Brantly was the first patient with Ebola to be treated at a hospital in the United States. Photo/ Samaritan’s Purse

JPS has a unique tie to Ebola. Dr. Kent Brantly, the first patient with the deadly virus to be treated at a hospital in the United States, did his medical residency at the Fort Worth hospital.

When he got sick in Liberia, “it gave you a sense this can happen to anyone,” Peebles said. “When it is one of your own, it really brings it closer to home.”

‘We’re in a better place’

The three people with Ebola in Texas served as a valuable reminder.

“This time it was Ebola, it could be something else, another disease that pops up that we’re not aware of at this point,” Peebles said. “This training has prepared us for whatever may come through our door that’s an infectious disease.”

Would nurses like Nina Pham and Amber Vinson have gotten sick today?

Last year, tens of thousands of nurses across the country protested for better safeguards against Ebola.

More than 7,000 nurses are members of the Texas Nurses Association. Executive Director Cindy Zolnierek said training has improved.

“I think hospitals have responded, many with a core team that is specially trained and has drilled in the preparation, particularly in the removal of protective equipment,” Zolnierek said. “I would like to think it wouldn’t happen to another caregiver, but there are no guarantees. But I think we’re in a better place than we were.”

Selected photos courtesy of The Dallas Morning News.