Cleaning Guys Environmental workers prepare to cover the apartment with plastic material in The Ivy Apartment complex

Cleaning Guys Environmental workers prepare to cover the apartment with plastic material in The Ivy Apartment complex where Ebola victim Thomas Duncan was staying in Dallas, Oct. 3, 2014 in Dallas. (Nathan Hunsinger/The Dallas Morning News)

After Ebola, Some Businesses Suffered, While Others Profited

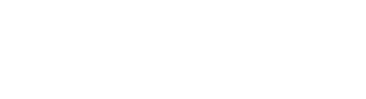

Even though Ebola never took root in the U.S., the virus seemed to spread throughout the economy. The most obvious financial cost was in Texas, at Texas Health Presbyterian Hospital in Dallas. But doctors and store owners in Vickery Meadow, the community near the hospital, also paid a price. And some people made money.

As news of Thomas Eric Duncan’s stay at Presbyterian hit the airwaves last fall, emergency room visits at Presbyterian plummeted. Thousands of patients went elsewhere.

This didn’t look good to investors. As bondholders speculated about Presbyterian’s ability to stay afloat, Moody’s revised its outlook on the hospital’s debt from “positive” to “developing.”

For the month of October 2014, revenue at Presbyterian declined more than $12 million. In November, revenue was down $8 million.

People didn’t want to go near the “Ebola” hospital.

Texas Health Presbyterian Hospital in Dallas on Oct. 1, 2014. (Jim Tuttle/The Dallas Morning News)

One practice ‘came to a screeching halt’

Dr. Alexandra Dresel is a surgeon with a private practice at the Presbyterian complex. Even though her office, a warm sixth floor suite, isn’t inside the actual hospital, Dresel found herself trying to calm patients down, trying to talk them off the ledge. They still canceled.

“The practice basically came to a screeching halt,” Dresel said.

Ebola’s arrival in Dallas affected all physicians affiliated with the hospital, she said.

“I’ve been in practice for 12 years and this was definitely my lowest collection for a fourth quarter of my entire career,” she said.

Some days, Dresel watched from her window as the media descended on Presbyterian. Duncan was getting worse. People were afraid of the situation getting out of hand.

Texas Governor Rick Perry held a press conference on Oct. 1, 2014.

“This case is serious,” Perry said. “Rest assured that our system is working as it should. … Professionals on every level of the chain of command know what to do to minimize this potential risk to the people of Texas and of this country for that matter. This is all hands on deck.”

Former Governor Rick Perry speaking at Texas Health Presbyterian Hospital on Oct. 1, 2014. Photo/Doualy Xaykaothao

What would happen with Duncan — and what would happen with the hospital?

Last fall, during the crisis, KERA asked Dr. Albert Wu, a professor of health policy at Johns Hopkins. He made a sound prediction.

“I expect this is just a blip,” Wu said. “I’m not sure they’re going to make their reputation on ‘we do the best job curing Ebola cases, send them to us,’ but they are getting their name mentioned. In the end, that might not be a terrible thing.”

Wu was right.

The hospital’s rebound was quick. Patients started coming through the doors at near-normal levels by early December, and Presbyterian’s financial report for 2014 showed it ended the year with an operating margin just a half a percentage point lower than the year before.

And that debt rating from Moody’s? That was upgraded, too.

There is still a lawsuit pending. In March, nurse Nina Pham sued Texas Health Resources for unspecified damages from her fight with Ebola.

Texas Health did reach a settlement with Duncan’s family to create a scholarship in his name. In May, chief operating officer Jeff Canose announced the hospital’s donation of $125,000.

“We are gathered … to announce fulfillment to a commitment that Texas Health Resources made to the family of Thomas Eric Duncan,” Canose said earlier this year. “To honor his memory by establishing a fund to help improve the health and medical care of people in Liberia, Mr. Duncan’s home country.”

Dallas attorney Charla Aldous represents nurse Nina Pham. “She’s been to hell and back,” Aldous said. Photo/Doualy Xaykaothao

The Cleaning Guys: ‘We’re proud of what we did’

The cleaning, the supplies, the overtime: How much did it cost Dallas-area taxpayers for all this?

Around $825,000, according to The Dallas Morning News.

A good chunk of that change went to three guys: Andrew Klein, Jon Schultz and Brad Smith of The Cleaning Guys.

They didn’t know it, but one phone call on Oct. 2 last year was about to change their lives.

On the other end of the line? The U.S. Department of Homeland Security.

The officials wanted to know if they’d be willing to clean ground zero of Ebola in the U.S. — the apartment in Vickery Meadow where Thomas Eric Duncan became sick. When they said yes, there was no manual. These guys would be the first cleanup crew in the country to walk into a home contaminated with the Ebola virus.

A worker with CG Environmental-Cleaning Guys sprays disinfectant outside the Marquita Street apartment building in Dallas

where a nurse infected with Ebola lives on Oct. 12, 2014. (Jim Tuttle/The Dallas Morning News)

“We were approaching it as if it were the worst chemical you could walk into and the worst bio cleanup you could take care of,” Smith said.

Outfitted in chemical suits, full-face respirators, gloves and boots, more than a dozen men went in to the Ivy apartment building. And the worst part? Not the scene inside, Smith said, but outside: the public’s reaction.

“Not only business but personal lives were a little up in arms, due to young children that a lot of employees have, including myself,” Smith said. “Dealing with the schools, baseball teams not wanting to necessarily be around our kids.”

Thomas Eric Duncan visited the Ivy apartments in Vickery Meadow before being transported to Texas Health Presbyterian Hospital in Dallas. Photo/Doualy Xaykaothao

Business was the same way. Smith said some customers they’d been working with for more than a decade asked them not to come on their property for 30 days.

“It was sometimes hard to swallow due to the fact that it’s the financial burden on the company,” Smith said. “When you think you’re doing the right thing and others don’t understand it quite the way you do.”

Just like with Presbyterian Hospital, business got back to normal. In fact, better than normal. The rugged-looking Cleaning Guys even ended up striking a pose for Vanity Fair magazine.

“We’re proud of what we did and we may have even gained more trust from our customers knowing that ‘Hey, these guys are able to handle that type of situation, surely they can handle ours,'” Smith said.

“I try to look at the bright side of everything. So far, it’s worked out well for us.”

Ebola the toy and Ebola the website

It also worked out well for a toy company. Giant Microbes started selling out of its stuffed Ebola virus toy. It looks like a plush, brown worm — with eyes.

Andrew Klein is the president of Giant Microbes in Stamford, Connecticut.

“We take some liberties with the products,” he said. “Our giant microbes actually have eyes on them to make them more fun and playful even though these are serious microbes that can cause harm.”

The furry Ebola, which goes for $10 retail, had been an average seller, Klein said. Then, last fall, there was a huge spike in demand. Educators, museums, science nerds — they all wanted one.

Then, just like with the Beanie Babies, the Ebola craze ended.

The Ebola Virus plush toy from Giant Microbes. Photo/ giantmicrobes.com

“Our sale of the Ebola giant microbe remains above what it was earlier, but it’s gone back towards an average seller,” Klein said.

Selling a few thousand extra toys is nothing compared to what Jon Schultz made from the Ebola scare in the U.S.

“We got $50,000 in cash and $150,000 in stock,” Schultz said.

All for a website domain: Ebola.com.

Schultz, with Las Vegas-based Blue String Ventures, buys domains, like Ebola.com, when they’re dirt cheap, and sells them when interest soars. He doesn’t consider anything wrong with that.

“I certainly wasn’t happy about the outbreak,” Schultz said. “I don’t feel guilty because we didn’t do anything wrong. We didn’t lie to anyone, cheat anyone, we didn’t sell any snake oil products at the website, and we in fact provided a link to Doctors Without Borders that thousands of people saw, and I don’t know how many people made donations.”

Fear dies down: ‘Time heals everything’

Of course, there were snake oil salesmen, peddling everything from Vitamin C and herbs to Nano Silver and snake venom. KERA reported last year that there aren’t any Ebola treatments approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration.

Dr. Alexandra Dresel is a surgeon with a private practice at the Texas Health Presbyterian complex. Photo/Lauren Silverman

“It’s like storm chasing roofers, who go and try to defraud people after a big storm,” SMU law professor Nathan Cortez says. “Some of them may be making an honest mistake. Other companies are trying to rip people off.”

Then, as the fear begins to decline, so do sales of hand sanitizer, hazmat suits, and stuffed animals modeled after the Ebola virus.

Dresel says people just start to forget.

“Time heals everything, people have short-term memories,” Dresel said. “Something else finally replaced the Ebola hype in the news. I can’t remember what it was. We were all like ‘we need something, a natural disaster. to come around and get us out of the limelight!’ And then people forget and they go back to their normal ways.”

Selected photos courtesy of The Dallas Morning News.