For several weeks last fall, North Texans were on edge because of Ebola. Fear traveled faster, and wider, than the virus. Here are eight lessons that Ebola taught North Texas.

Prior to Sept. 30, 2014, North Texans were more worried about the flu season than the Ebola virus. Then, in a Dallas emergency room, Thomas Eric Duncan was diagnosed with Ebola. A week later, he died. Two nurses who treated him, Nina Pham and Amber Vinson, became infected, but recovered.

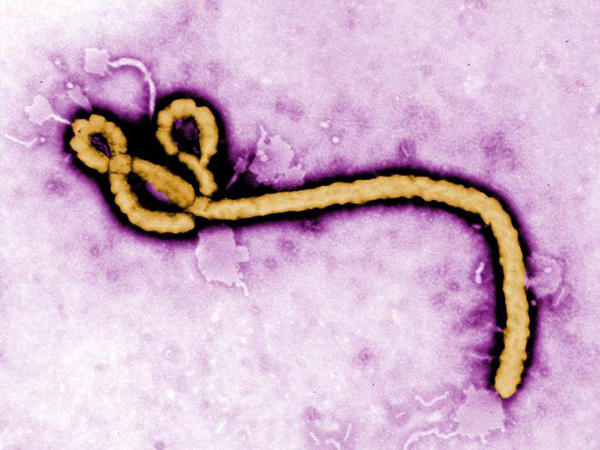

1. Ebola does not spread easily.

Americans didn’t know much about Ebola prior to Thomas Eric Duncan’s diagnosis, other than it had become an epidemic in West Africa.

Though Ebola can be deadly, it’s less contagious than other diseases. But the virus can be spread through direct contact with an Ebola patient’s blood or bodily fluids.

“Ebola is not spread through the air, by water, or in general, by food,” the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention says. “However, in Africa, Ebola may be spread as a result of handling bushmeat (wild animals hunted for food) and contact with infected bats. There is no evidence that mosquitoes or other insects can transmit Ebola virus. Only a few species of mammals (e.g., humans, bats, monkeys, and apes) have shown the ability to become infected with and spread Ebola virus.”

In Dallas, only three people became infected with Ebola. About 175 people were monitored for 21 days for symptoms. They were in contact with Duncan, Pham or Vinson or handled specimens or medical waste. The last people were cleared and declared symptom-free on Nov. 7.

A microscopic view of the Ebola virus. Credit/CDC

2. In the United States, most hospitals weren’t ready to treat Ebola.

The Ebola outbreak in West Africa became an epidemic partly because people infected with Ebola weren’t aware that they were sick until it was too late. The disease starts with a fever, and quickly escalates. Dwindling medical supplies, insufficient protective gear and burial practices also caused the virus to spread quickly.

When Duncan was diagnosed with the Ebola virus, doctors were confident that a similar outbreak wouldn’t occur in the United States.

“The difference between a rural hospital in West Africa and a 21st century U.S. hospital is so massive,” Baylor infectious disease expert Dr. Cedric Spak said last fall. “We have excellent hospitals here. If there’s an individual in Dallas who’s unfortunate to have Ebola, his best chances of surviving are to be at a hospital in Dallas.”

In late September of 2014, when Duncan first showed up in the emergency room at Texas Health Presbyterian Hospital, no one had connected the dots between his travel history in Africa and his symptoms. He was sent home with antibiotics. When he was admitted a second time, there was confusion among hospital workers over which infection control protocols to follow.

Before Duncan’s diagnosis, only four U.S. hospitals were specially equipped to handle the virus. Two of those facilities ended up treating Nina Pham and Amber Vinson, the nurses who contracted Ebola while caring for Duncan. After Duncan died, more specialized Ebola units were established across the country, including two in Texas.

Texas Health Presbyterian Hospital in Dallas on Oct. 1, 2014. (Jim Tuttle/The Dallas Morning News)

3. In Texas, there wasn’t a clear chain of command at first.

Soon after Duncan’s diagnosis was announced, Texas Governor Rick Perry, Dallas Mayor Mike Rawlings, Dallas County Judge Clay Jenkins, Dallas County Health & Human Services Director Zachary Thompson and other public officials presented a united front at a press conference. Behind the scenes, however, the chain of command was unclear.

Jenkins thought the CDC would assume control; instead, the federal agency offered guidance. Jenkins joined David Lakey, the Texas health commissioner, to create a so-called incident command structure to make sense out of the chaos.

Once the command structure was sorted out, there were still bureaucratic hurdles to jump over. One significant example: It took days for cleaning crews to come out and remove the waste inside the apartment where Duncan stayed because appropriate permits weren’t in place. (Learn more from Jenkins about last year’s events.)

4. The CDC can get things wrong.

Local and state officials turned to the CDC for guidance. The agency sent disease detectives to Dallas to find people who had contact with Duncan and monitor them for symptoms.

The CDC also had recommendations in place for protecting and controlling the virus. But there was confusion over those guidelines, in particular the use of personal protective equipment and how to manage waste.

Pham, like other Texas Health Presbyterian Hospital workers caring for Duncan, wore full protective gear, which included a gown, gloves, mask and shield. When she reported a low-grade fever and was placed in isolation, a federal health official said her Ebola diagnosis was the result of a breach of safety protocol.

In late October, the CDC announced it was tightening guidance for health care workers “to ensure there is no ambiguity.”

A year later, a report found nurses improvised their personal protective equipment and had learned conflicting methods of donning and removing protective suits. Unclear CDC guidance over waste management may have also exposed workers to the virus.

The CDC would also face scrutiny for no enforcing or recommending travel bans for the people who were being monitored for Ebola symptoms. A CDC official gave Vinson clearance to board a plane from Cleveland to Dallas Oct. 13 when she reported a temperature below 100.4 degrees. The next day, she had a fever. On Oct. 15, Vinson was diagnosed with Ebola.

Ebola responders. Photo: Samaritan’s Purse

5. Fear trumped reason.

Epidemiologists repeatedly said Ebola couldn’t be spread unless a person who was in contact with someone who had the virus started showing symptoms. That didn’t stop people from panicking, though. In the middle of flu season, people canceled medical appointments. Many patients stayed away from Presbyterian hospital. Schools in Texas and Ohio were closed so they could be cleaned. A community college in Corsicana refused to admit students from Ebola-afflicted countries. When a Dallas County deputy went to a CareNow clinic in Frisco because he wasn’t feeling well, the clinic shut down once it was known that he had entered the apartment of Louise Troh, Duncan’s fiancée.

Some media outlets sometimes fanned the flames of panic – panic that was ridiculed by TV host Jon Stewart.

Get More: Comedy Central,Funny Videos,Funny TV Shows

6. Community leaders worked to calm fears.

Despite fears over the potential spread of the Ebola virus, North Texas community leaders pitched in to offer support to Duncan’s fiancée and her sons. Louise Troh’s pastor, George Mason of Wilshire Baptist Church, visited her every day even when it was unclear if she might contract Ebola.

When the Troh family was moved to another home, Dallas County Judge Clay Jenkins insisted on driving them there. Dallas Mayor Mike Rawlings initially offered his son’s home for the family to stay, but the Catholic Diocese of Dallas provided a home instead at a conference center.

Mark Romney leads a small group prayer during a vigil in memory of those who have lost their lives to Ebola and the ones caring

for those infected, Thursday, October 23, 2014 at the chapel of Thanks-Giving Square.(Tom Fox/The Dallas Morning News)

7. We’re not isolated from the world.

As the Ebola crisis was raging in West Africa, it was mostly seen as “their” problem, even when American doctors and volunteers like Dr. Kent Brantly and Nancy Writebol contracted the disease and were flown back to the U.S. for treatment. With international travel, though, experts said Ebola in America was bound to happen. And it did.

There were still Ebola diagnoses in the United States after Duncan, Pham and Vinson contracted the virus. In October 2014, Dr. Craig Allen Spencer was diagnosed with Ebola in New York City; he had been working with Doctors Without Borders in West Africa. Spencer survived. In November 2014, Dr. Martin Salia, a surgeon diagnosed with Ebola in Sierra Leone, was flown to Nebraska for treatment. Days later, Salia died.

These cases prompted calls from lawmakers to enforce travel bans to and from West Africa, and some airports conducted extra screenings for travelers.

8. People will take advantage of a sensitive situation.

There is no known cure for Ebola, but that didn’t stop some companies from marketing products claiming to kill the virus. Pham and Vinson were able to beat Ebola thanks to experimental drugs, plasma from other Ebola survivors and catching and treating the disease early.

The panic over Ebola didn’t stop others from using it as Halloween inspiration.

Retailer BrandsOnSale sold Ebola costumes for men and women. There was a “sexy version” of the Ebola containment suit, and the retailer marketed the frocks as “the most viral costume of the year.”

In North Texas, James Faulk decorated his University Park house with Ebola-themed decorations, such as barrels labeled as biohazards and caution tape draped around his yard. After police were called to his house, he put up a Halloween sign. Though some neighbors thought the decorations were funny, others thought it was too soon to make jokes about Ebola. Faulk tried to remedy the situation by offering to donate money to Doctors Without Borders, but the nonprofit refused his donation.

Selected photos courtesy of The Dallas Morning News.