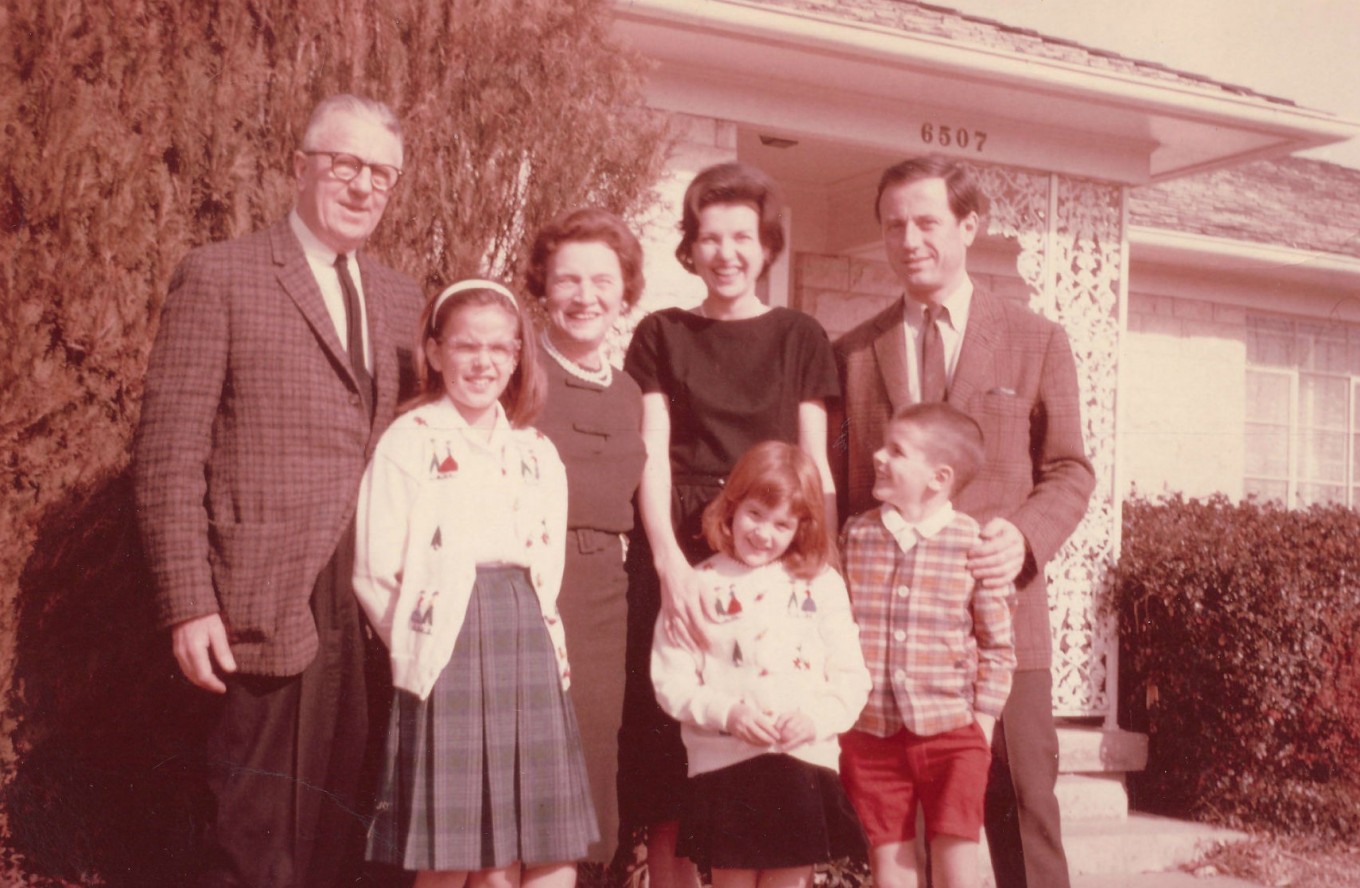

Courtney Sands, center, and her family stand in front of her Dallas home in the 1960s. Courtesy Heather Stephens

Courtney Sands, center, and her family stand in front of her Dallas home in the 1960s. Courtesy Heather Stephens

There’s No Place Like Home

Home design and technology have changed dramatically over the last two decades. Someone who’s fractured a hip might once have been forced into a nursing home. Now it’s possible to “age in place.” Design breakthroughs make that possible.

For Courtney Sands, last year was a nightmare.

“Let’s just erase 2013 from our memory book,” she said. “Several surgeries and just one difficult time after another.”

In December, at age 81, Sands landed in a hospital after slipping and breaking her wrist and hip. But she was determined to get back to her beloved home. Her daughter, Heather Stephens, a nurse who lives in California, wasn’t so sure.

“To be honest with you, I was hoping she would not want to return home,” Stephens said.

Home is a one-story North Dallas ranch house where Sands has lived since 1963. Not much inside had changed since.

“She really wasn’t safe,” Stephens said. “She would walk around the house hanging onto furniture or gripping door jams.”

Stephens faced a challenge: “Make the house as safe as possible for her to be there.”

Ninety percent of people over the age of 65 say they want to stay in their home as long as they possibly can, according to the AARP.

Sands is no exception. Sitting next to her living room piano, she said she loves everything about her house. There’s an old gas stove in the kitchen, vintage woven cane chairs, white iron chairs, original sky blue tile and floral wallpaper.

“[It’s a] good neighborhood, pleasant surroundings,” Sands said. “It’s home.”

On a hunt for trip hazards

Instead of leaving, Sands and her daughter hired Adam Mandel, a certified aging-in-place specialist with a company called Independent Living Design.

Courtney Sands’ 80th birthday in 2012. Last year, she slipped at home, fracturing her wrist and hip. Courtesy Heather Stephens

One of the first things he does when he visits a home? Look for trip hazards.

That can be as simple as tossing throw rugs or rearranging furniture. One slip can lead to a cascade of problems, from surgery to physical therapy to assisted living.

Narrow doors are an issue. Mandel’s clients often leave their walkers outside the bathroom since they can’t get through the door.

“That’s when the fall happens,” he said. “They’re grabbing onto counters or sinks. Something happens. They fall.”

Mandel recently walked through Sands’ home, showing the improvements he made. He expanded the 24-inch door frames to 32 inches – and kept the sky blue tiles and pink wallpaper almost undisturbed.

This leaves Sands with no excuse not to use her walker. Now she can be “married to her walker,” her daughter said.

Mandel pointed out the bathroom shower.

“All these falls, a majority of them take place in the bathtub or shower because it’s a wet area and it gets really slippery,” he said. “I want to put in really good grab bars.”

Several silver bars are anchored to the wall for Sands to grab. Nearby is a bench she sits on when she bathes. The tub is also outfitted with an adjustable sliding shower head.

Sands admits she didn’t like the idea of grab bars. At first, she thought they looked like prison bars. But now she likes them.

“They are my good friends now,” she said.

No Evel Knievel ramps here

Her best friend, though, is a 16-foot-long wooden ramp that makes it easy for her to get in and out of her house – but not one that dominates the front porch.

“If you want a basic ramp, I like it in the garage because it’s not detracting from the curb appeal of the house,” Mandel said. “It’s tucked away here and nobody needs to know there’s a ramp.”

The ramp is designed with a gradual slope that’s easy for someone in a walker or wheelchair to maneuver.

Mandel often walks into garages where well-meaning neighbors or church friends have installed a ramp – but it’s usually way too steep.

“It’s sort of like an Evel Knievel ramp,” he joked. “If she wanted to ride a wheelchair and jump over 20 busses, this is an appropriate ramp. But for safely getting in and out of the house in a wheelchair or walker, we definitely need to have this slope.”

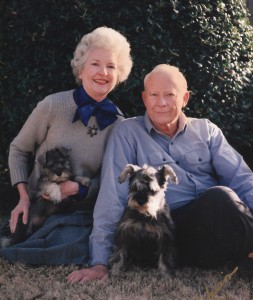

Courtney Sands with her late husband, Bill, in 1991. Courtesy Heather Stephens

A Cornell University study showed more than half of so-called low-needs nursing home residents could be living at home if they had adequate support, such as a house with ramps, wide doorways and good lighting.

Making homes accessible to all without sacrificing style is the mantra behind the growing aging-in-place and “universal design” movement.

“As our population is aging, this business is just going to get bigger and bigger and there’s going to be more demand,” Mandel said.

But it can be expensive to renovate an old home, especially if it’s two or three stories. An elevator costs anywhere from $20,000 to $100,000. A chair lift can cost $5,000. That’s why Mandel tells people who are building a home to plan ahead.

More modest upgrades, like those in Sands’ house, cost less than $8,000. She says it was well worth it.

“My fan club was all saying ‘Oh, you can stay at your house; it’s wonderful; it’s going to be beautiful; it’s going to be just fine,’” Sands said. “And it is.”

The improvements

Here are some of the things that Adam Mandel, an aging-in-place specialist with Independent Living Design, did to improve Courtney Sands’ home and make it safer:

- Built a ramp in the garage.

- Widened doorways in bathrooms.

- Added small ramps at entrances into the home.

- Installed grab bars in the shower.

- Installed railings on the front porch and on the steps of a walkway.

The vast majority of hip fractures are the result of a fall, and more than half of all falls happen at home.  Many of these falls could be prevented by making simple changes to the lighting and arrangement of furniture. How can you make your bedroom fall-proof?

Many of these falls could be prevented by making simple changes to the lighting and arrangement of furniture. How can you make your bedroom fall-proof?