Every year, 300,000 Americans who are 65 and older break a hip. Nearly all of those fractures are treated with surgery.

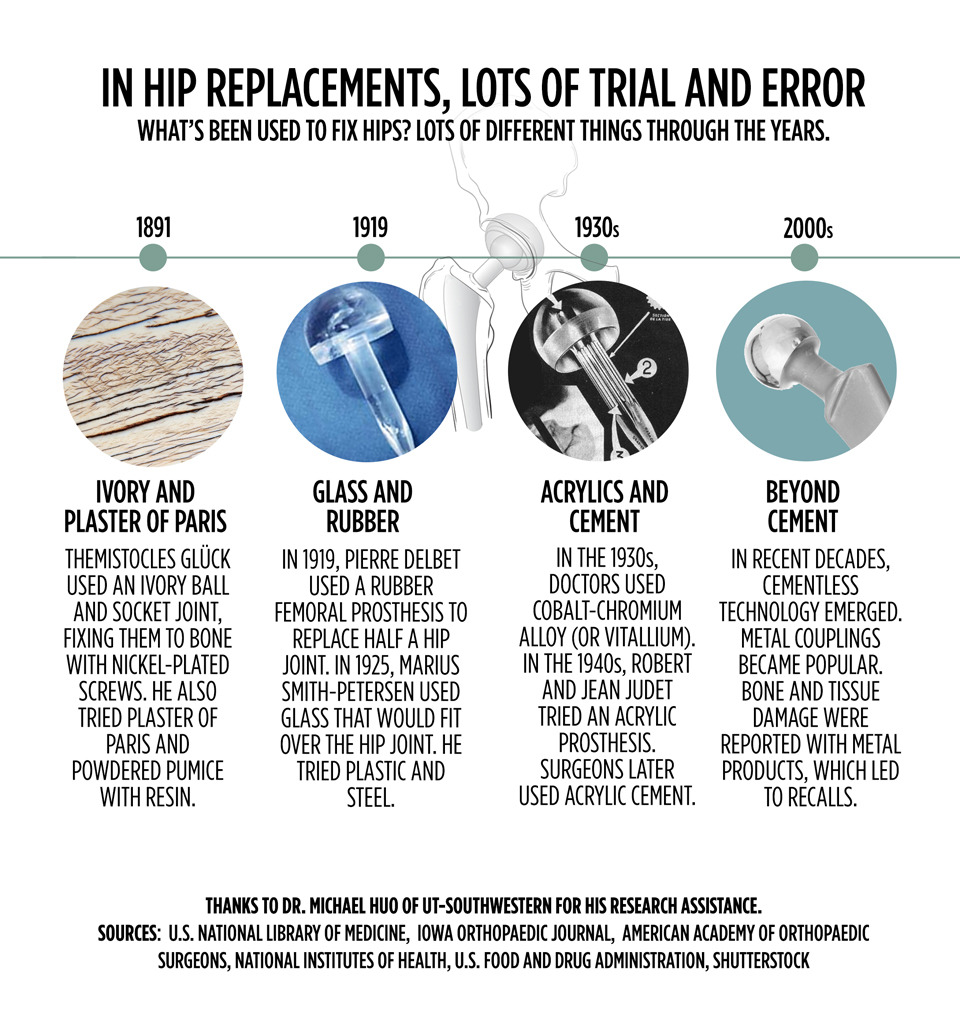

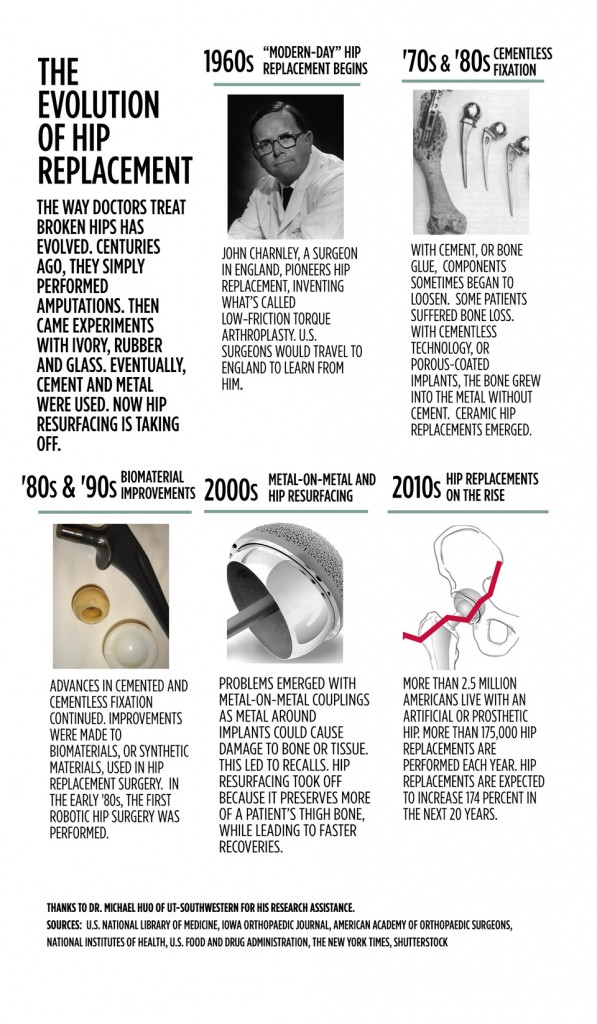

Repairing a broken hip has come a long way in the last century — from ivory and rubber to precision titanium implants. Technology will change how surgeons fix fractures in the future.

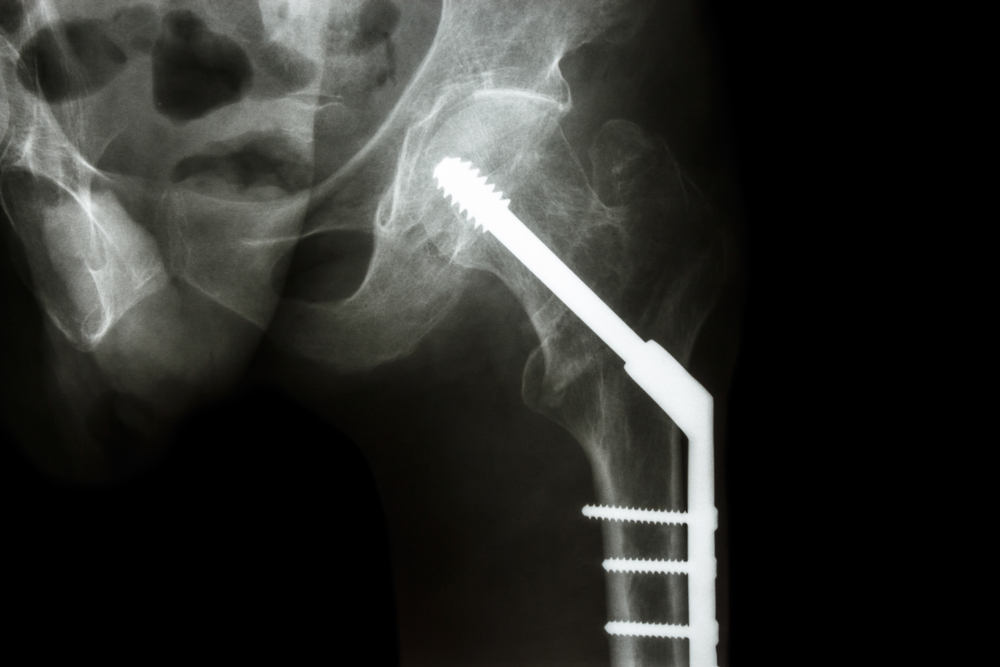

Plates and pins, screws and rods – you could call them hip-fracture hardware.

The era of modern hip replacements started in the 1960s – and surgery techniques and biomaterial designs have evolved. Today, about 2.5 million Americans live with an artificial hip.

Dr. Michael Huo, an orthopedic surgeon at UT-Southwestern, has repaired and replaced hips for decades. Many fractures can be repaired with screws and metal plates, but full replacements are becoming more popular.

Dr. Michael Huo is an orthopedic surgeon and joint replacement specialist at UT-Southwestern in Dallas. Credit: UT-Southwestern

Graphic by Ryan Tainter

A century ago, surgeons used ivory and even rubber for hip replacements. Today, most are titanium, other metals or plastic. Huo says doctors often use a combination for the ball portion of the hip, and the stem, which inserts into the femur.

To attach these parts, surgeons traditionally used something called bone cement. But it poses some risks for elderly patients, Huo says. Today, doctors use implants with a porous coating, which promotes natural bone growth to secure the new hip.

“Since the 1990s, the technology and the surgical technique have evolved to the point that many of these operations are done without the use of bone cement,” Huo says.

‘GPS for the body’

Regardless of what materials are used, the implant has to be positioned just right. New technology is helping with that, too.

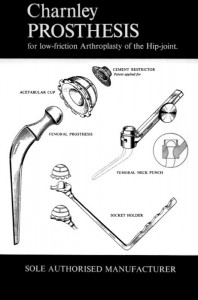

John Charnley is considered the father of modern hip replacement. He introduced low-friction anthroplasty in the 1960s. Credit: American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons.

“One key that keeps evolving is image-guided surgery, basically a GPS for the body,” says James Laskaris, a clinical analyst at MD Buyline in Dallas, which helps hospitals choose medical products.

He says image-guided surgery is booming.

“Clinical studies show that it improves the accuracy so much more by using image-guided surgery,” Laskaris says. “Years ago … a surgeon would just say: ‘Well, here’s where it should go.’ Now they have the opportunity to be able to align it perfectly because the computer is telling them, ‘Yes, this is where it should be.’”

But in image-guided surgery, doctors are relying on a historic image – usually an X-ray taken days or weeks earlier. What if a surgeon wants to see in real-time whether there are any other fractures or changes in the hip while making repairs? They can turn to 3-D fluoroscopy. It’s essentially a live X-ray.

“The key is it has the ability to send the image to the image-guided surgery device, so now everything is married together in real time,” Laskaris says. “It’s no longer: ‘OK, we’re going to bring the X-ray tech in [and] develop it.’”

Graphic by Ryan Tainter

The future: tiny sensors

While image-guided surgery and 3-D fluoroscopy help save time and increase accuracy in the operating room, there’s also a push to improve recovery after hip surgery.

James Laskaris is a clinical analyst at MD Buyline in Dallas. Credit: MD Buyline

One day, tiny implantable devices could be placed in the body and make it easier to monitor hip replacements after patients leave the hospital, Laskaris says. The hope is that nanotechnology and new materials will change the hip implants of the future – making them last longer and more reliable.

“Pacemakers do it already,” Laskaris says. “They tell you if there’s something wrong with you or something wrong with the pacemaker. … It’s a pre-warning sign that can determine: ‘Is there too much stress on the implant they put in?’ Maybe there’s an infection that we can’t detect yet. The sky’s the limit.”

The vast majority of hip fractures are the result of a fall, and more than half of all falls happen at home. Many of these falls could be prevented by making simple changes to the lighting and arrangement of furniture.

How can you make your bedroom fall-proof?

Selected cover images from Shutterstock and American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons