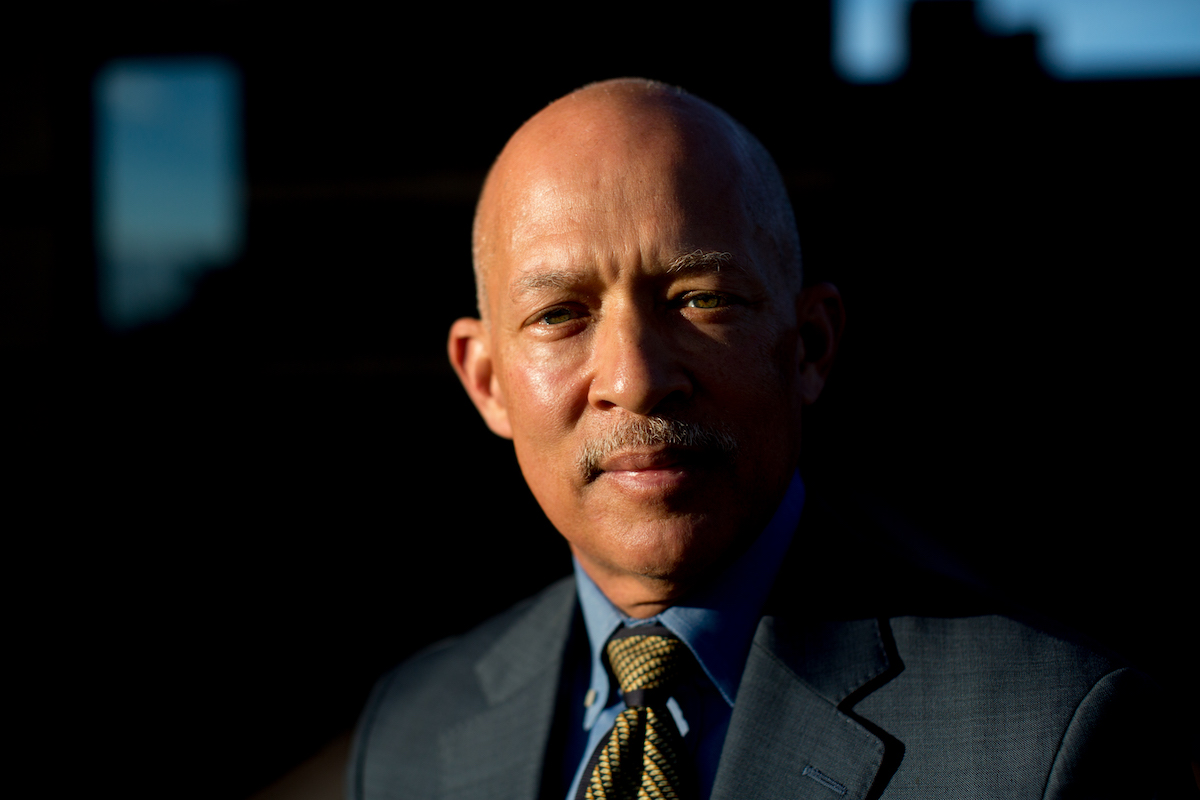

John Creuzot in his private law office. In January, he'll relocate to the district attorney’s offices in the Frank Crowley Courts Building. (Photo: Allison V. Smith)

John Creuzot in his private law office. In January, he'll relocate to the district attorney’s offices in the Frank Crowley Courts Building. (Photo: Allison V. Smith)

How John Creuzot Plans to Reform Criminal Justice In Dallas County

When John Creuzot takes office in January as Dallas County district attorney, he promises to usher in a new era of prosecution.

“It’s time for real criminal justice reform in Dallas County and we’re going to deliver,” he proclaimed to an enthusiastic crowd of Democrats gathered on election night. Creuzot won 60 percent of the vote, beating out Republican incumbent Faith Johnson.

Standing on the stage at the Hilton Regency ballroom, Creuzot laid out an expansive agenda, pledging to decline prosecution for first-time marijuana possession, to pursue drug treatment for drug offenders instead of sending them to prison, to refuse to revoke probation for technical violations, to bulk up a conviction integrity unit to make sure wrongfully convicted people don’t stay in prison, and to fight for bail reform.

“How about an end to the excuses?” he bellowed to cheering supporters. “How about making sure that if you’re poor you don’t get ripped off by the criminal justice system?”

Homeless people are “generally the ones who are taken to jail, but they’re also the ones who are in greater need of services,” Creuzot says. (Photo: Allison V. Smith)

This kind of speechifying doesn’t always seem to come naturally to Creuzot, a criminal justice wonk who says his policy reforms will be based in rigorous data gathering and a careful study of best practices.

More typically, Creuzot delivers withering analyses of the criminal justice system’s flaws and excesses in a straightforward way. It takes a moment to sink in that, this time, he sounds more like an activist than someone who’ll be the top law enforcement officer of Texas’ second-largest county.

“Well, I mean, historically, if you’re poor you’re more likely to go to the penitentiary,” he says simply, adding that little has changed.

Poor people and people of color are more likely to be arrested, to get charged more severely, get offered less-lenient plea deals and get longer jail and prison sentences; just look at the data, he says.

Tackling drug sentences

Creuzot, a one-time prosecutor and current-day defense attorney, made a name for himself as a judge by launching Dallas County’s first drug court back in 1998, offering drug abusers addiction treatment in lieu of incarceration. It was effective, he’ll tell you: a 68 percent reduction in re-arrests and $9.43 in criminal justice cost savings for every dollar spent on the drug court.

Today, resources in the district attorney’s office are too-often spent on small-time and non-violent offenses tied to larger issues like poverty, addiction and mental illness — resources, he says, that should be freed up to focus on prosecuting violent, hardened criminals.

Drugs and incarceration

Sentencing policies during the War on Drugs era led to a steep growth in imprisonment for drug offenses. The number of Americans incarcerated for drugs has increased from 40,900 in 1980 to 450,345 in 2016. Also, sentencing laws like mandatory minimums keep many people convicted of drug offenses in prison for longer periods.

In 2017, the district attorney’s office filed more than 7,000 misdemeanor pot possession charges — 4 ounces of marijuana or less. Creuzot says that exacerbates racial disparities because people of color are more likely to be charged with small-time drug crimes than whites, despite equal drug usage.

That same year, the DA’s office charged more than 600 homeless people with criminal trespass, which Creuzot says amounts to charging chronically homeless people for being homeless.

“They’re generally the ones who are taken to jail, but they’re also the ones who are in greater need of services,” Creuzot says. “They’re not going to get those services in the Dallas County jail or other county jails, so it begs the question, why are we putting them in jail?”

For Creuzot, the office needs more than a change in policy. He wants a complete reorientation of prosecutorial philosophy. It’s the rallying cry of a growing cadre of reform-minded prosecutors nationwide.

» who gets charged with a crime

» what charges get dropped

» whether to pursue a death sentence

» whether to charge a youth as an adult

» whether a person can enter a diversion or treatment program

» plea deals that set a person’s punishment

“What we see John Creuzot doing, what we see others doing in other parts of the country, is really taking to heart a different starting point for prosecutors,” says Miriam Krinsky, the executive director of Fair and Just Prosecution.

Krinsky, a former federal prosecutor, works with about 30 local prosecutors who want to rein in long-standing punitive policies that they say have marginalized communities, quintupled the nation’s prison population and, ultimately, proven largely ineffective at increasing public safety.

“When we look around the country, we do see that communities that reduce their rates of incarceration have also seen that crime rates have fallen at the same time,” Krinsky says.

Fair and Just Prosecution released a blueprint for prosecutorial reform earlier this month, laying out 21 steps to make the justice system more transparent, more equal and more effective. Prosecutors have a powerful position as decision-makers in the criminal justice system, the group argues, so they have an important role to play in ending mass incarceration.

“We really should be using incarceration as an exception to the rule,” Krinsky says. “Incarceration should really be used for those few cases where there really is no alternative but to remove that individual from the community. And, unfortunately, that hasn’t been the starting point in the past.”

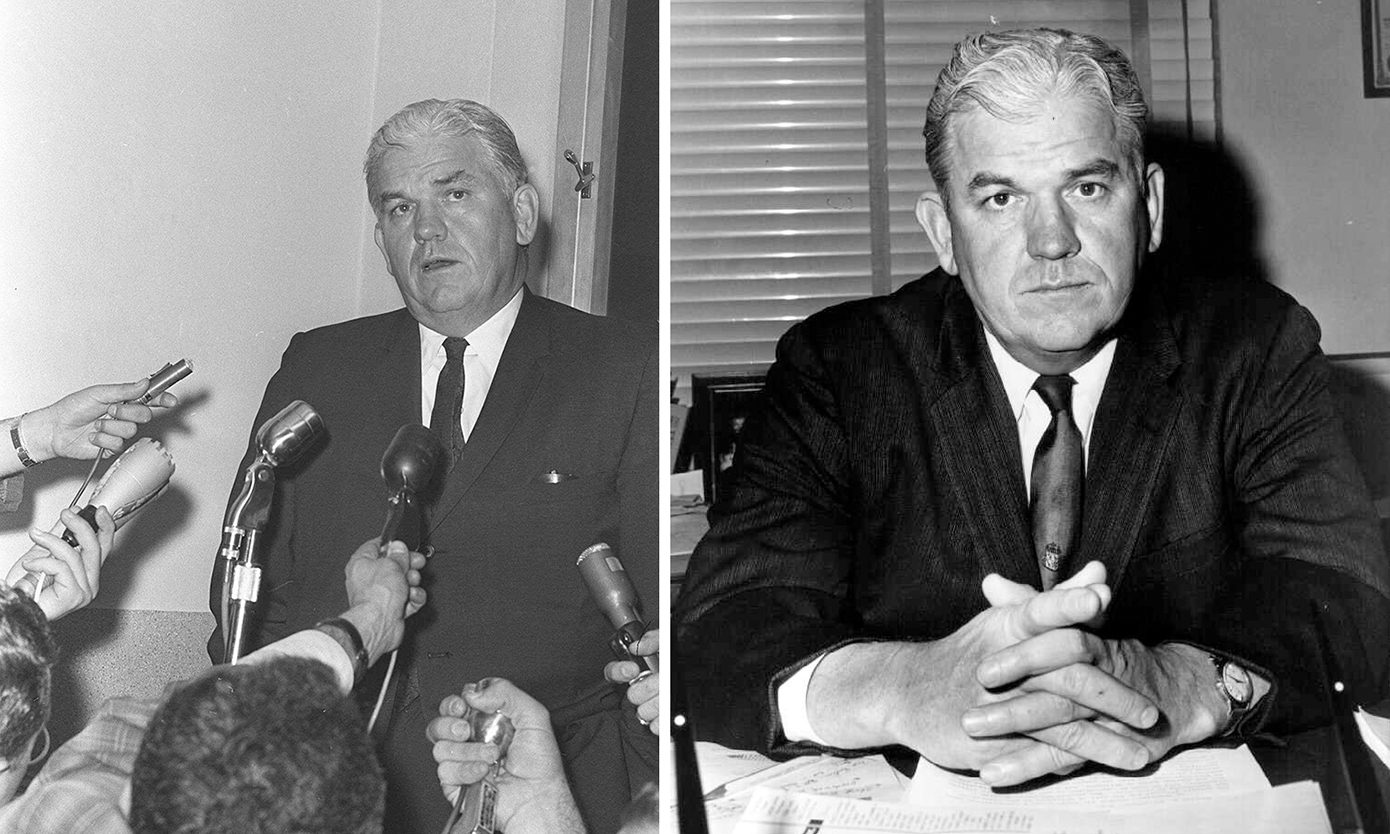

Wade: ‘A reputation for strong prosecution’

For decades, district attorneys across the country were judged for how tough they were on crime. And no one was tougher than Henry Wade, the legendary Dallas County DA from 1951 to 1987. The cigar-chomping embodiment of Texas justice was the Wade in Roe v. Wade. He prosecuted Jack Ruby for killing the man who assassinated President John Kennedy.

For 36 years, Wade oversaw an office that piled up conviction after conviction on high-profile cases and against low-level offenders.

“I hope I have a reputation for strong prosecution,” Wade told KERA in 1986. “I’m trying to build one.”

In the years since, that reputation for strong prosecution came to be seen as a win-at-all-costs approach that prized conviction over justice.

In 2007, Craig Watkins drew national attention as the first black DA in Texas, and for setting up a conviction integrity unit in Dallas that exonerated innocent people who’d been wrongfully convicted, many by Henry Wade’s prosecution machine.

“We threw this whole idea of dispensing justice out the window. We didn’t care if a person was innocent or a person was guilty,” Watkins said in a 2008 speech. “We just cared that we could wave that banner to the person who was voting and say that we got a conviction, and our conviction rate was high.”

These days, criminal justice reform has become a cause that spans the political spectrum.

States have embraced it as prison populations have ballooned despite historically low crime rates. Texas has led the way on a host of reforms, many of which are replicated in a federal reform bill that President Donald Trump has praised and U.S. Sen. John Cornyn of Texas co-sponsored.

In the Dallas DA’s office, Watkins was followed in the office by Susan Hawk, a Republican who launched a program to divert people with mental illness and young, first-time offenders away from prison.

Faith Johnson was appointed to the office when Hawk stepped down in 2016, and Johnson held events to help people expunge old arrest records and won acclaim for successfully prosecuting the white Balch Springs police officer who shot and killed a black teenager, Jordan Edwards.

Complicated criminal justice ecosystem

Dallas County’s chief public defender, Lynn Richardson, says talk of reform from prosecutors hasn’t, for a lot of reasons, amounted to the kind of fundamental change the system needs and that Creuzot has promised.

“I’ve seen it before, where you’ve had district attorneys who’ve gotten up there and said, ‘I’m going to do X, Y and Z,’ and they didn’t do it,” Richardson says.

Lawyers from Richardson’s office will be on the opposite side of cases from Creuzot’s prosecutors, and she says she’s warned her team to be ready for tough, smart prosecution of violent, repeat offenders.

Nonetheless, she says she is excited by Creuzot’s election, and thinks he has the kind of technocratic approach that could affect the kind of sweeping change he’s promised. As evidence, she says, just look at the drug court he set up 20 years ago.

“He was the one that took that issue, [and said] instead of sending people to prison, we’re going to send people to treatment, we’re going to get them the treatment they need, the resources they need so they don’t keep coming back in the system over and over again,” Richardson said. “When he started that, there weren’t a lot of people on board like there are now.”

Creuzot stands outside the Frank Crowley Courts Building in Dallas. (Photo: Allison V. Smith)

Richardson says reform often doesn’t happen because it’s hard, and a DA, though powerful, is just one player in a complicated criminal justice ecosystem: Judges decide whether to waive court costs for poor defendants. Police decide who gets arrested and who doesn’t.

Creuzot will need buy-in from state lawmakers and county commissioners. Plus, he has to build and maintain support for his agenda, both among the public and within the office he’ll take over in January.

“Not everyone in a prosecutor’s office is going to embrace or subscribe to the new thinking that the DA brings,” says Krinsky with Fair and Just Prosecution. “And breaking down the culture and trying to give a new vision to the prosecutors, some of whom have been there for decades, is always a challenge.”

Creuzot, for his part, says he’s up to the challenge, and says that his agenda is in line with the direction of the state. He’ll be one of five reform-minded DAs in Texas. And he points to a decade of criminal justice reforms in Texas that have begun to shrink the biggest prison population in the country.

“We’ve actually closed eight prisons, but we will probably be closing more,” Creuzot says. “We think that the policies that we implement will help us get there. Harris County will do so. We think Bexar County will do so. So that’s billions and billions of dollars in taxpayer savings.”

That’s the other price of prison to consider: It costs taxpayers a lot of money to pursue tough-on-crime policies, Creuzot says, especially if they don’t make us any safer. And Dallas County, he says, should lead the way.