Principal Earl Gilmore welcomes Edison students on the first

Principal Earl Gilmore welcomes Edison students on the first day of STAAR testing on April 10, 2018. Photo: Lara Solt

Dallas School To Close Even Though District Tried To Save It

For five straight years, Thomas Edison Middle Learning Center has failed to meet the state’s minimum education standards. The West Dallas school named for America’s great inventor couldn’t find a way to earn to a passing grade. One more failing round of tests and the state would shut it down or even take over the district. So instead of waiting on the verdict, Edison will close its doors.

On a brisk, bright Tuesday morning, a handful of community volunteers, along with Principal Earl Gilmore, hold signs and cheer on students walking into Edison Middle Learning Center. They’re encouraging these kids to pass the annual STAAR tests. This is not the scene you might expect on the first day of statewide testing at a perennially failing school.

Students Jakori Daniels and Flor Morales say they’re embarrassed — sort of.

“It really does make me happy to see them out there, standing out there,” Daniels said. “I think they really do believe in us, and you know…give you a grin on your face.”

Morales chimed in: “I feel supported and feel like I can do it, and like, it’s helpful.”

For the last five years, test scores here have needed all kinds of help. The state’s lowest possible rating given to a school each year is “Improvement Required.” If a school fails five years or more, the Texas Education Agency can shut it down. (For more on accountability, read the introduction to this series.)

Stress at home

Meiosha Fuller has taught social studies at Edison for four years. She remembers what the school was like when she started: chaos.

“When I walked in, I’m looking for the theme song, ‘Welcome to the Jungle,’ literally,” Fuller said. “They were having a good time. If you corrected them or anything that they did, the teacher was the enemy at the time.”

Teachers were heroes, not enemies, to Fuller. She grew up poor, in a dysfunctional family, in East Texas. With many of her students in West Dallas, it was like looking at a mirror. Maybe school for them could be what it was for her – a life preserver.

“That was my way of getting out of the hood,” she said. “I was smart. I did my work, but I was one of those kids that was quiet. I didn’t want any light to be shining on me just in case someone would know what I’m going through at home.”

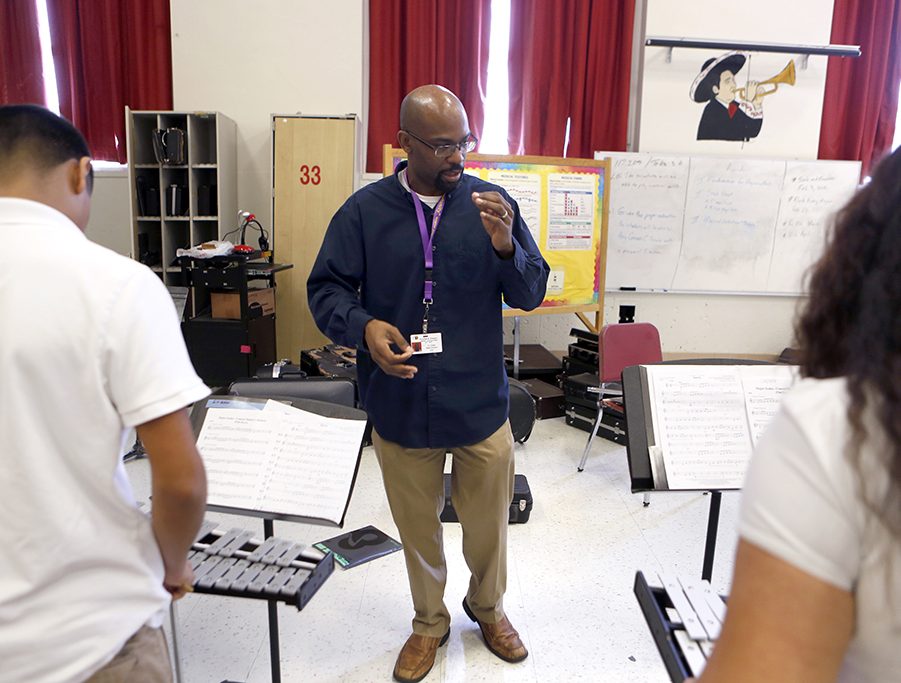

Thomas Edison Middle Learning Center band students (from left) Alexis Viviana Razo, Jose Carmen Yanez Dela Cruz and Alyssa Navarro talk about their experiences at Edison on March 28, 2018. Photo: Lara Solt

Many of these kids, including eighth-grader Alexis Razo, have stuff going on at home.

“My stepdad would constantly abuse my mom. I tried getting [Child Protective Services]. And my mom just said, ‘No,’ and she said, ‘What happens at home stays at home,’” Razo recalled. “So I eventually just got tired of it [and] said, ‘You know what? I’m not going to tell you how to live your life. I just don’t want to be in an environment like that.'”

She left to live with her dad.

Razo says home can mess with school.

“The stress is a lot,” she said. “Sometimes I just get frustrated. My frustration — I get it out in school sometimes. And at times I’ve just walked out.”

Switching focus

There’s a lot of frustration here.

Part of the roof collapsed this year. Kids see rats on the ground and mold on the walls. The building’s less than half full. Nine out of every 10 students are economically disadvantaged. The majority of West Dallas residents speak Spanish at home — another hurdle for schools.

So the district made a bold play: Edison became one of the first seven ACE schools in Texas. It stands for Accelerating Campus Excellence.

After the first year of the program, six of those struggling schools turned things around earning a “Met Standard” rating and nine distinctions among them.

Jolee Healey oversees the ACE program, which imports all new top-rated, highly paid faculty and staff. The school day is longer. The district also adds more resources and programs. Healey said in the second year of ACE, the same six schools earned 13 distinctions.

The only exception was Edison.

The ACE program has now been adopted by other North Texas school districts, including Richardson and Garland.

In the case of Edison Middle Learning Center, Healey says her team underestimated some challenges from the start. Then the principal changed – and it’s the leader who sets the tone. Just ask Earl Gilmore, Edison’s last-chance principal.

“When I came in, I wanted to make sure that I focused on discipline, structure, procedures, routines. Those things were not here,” Gilmore said. “Kids will not learn no matter how good the teacher or administrator may be. I have to have adequate structure in the building.”

After Gilmore’s first year, Edison failed again, getting its fifth consecutive failing rating.

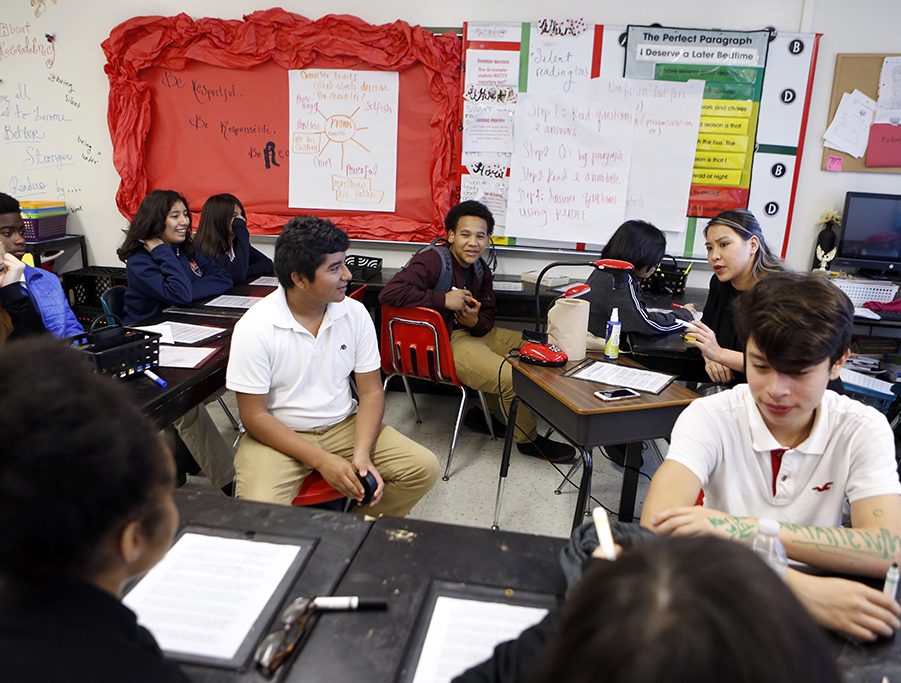

Principal Earl Gilmore greets sixth-grader Kuntelleon Spikes in between classes at Edison Middle Learning Center on March 28, 2018. Photo: Lara Solt

“If I had to go back and do it all over again, I would have provided the structure, but then we know that instruction is the most vital piece of meeting standards,” Gilmore said. “And I would have actually put more emphasis on the instruction piece.”

That’s what Gilmore focused on this year. He says internal assessments in Edison’s weakest areas have shown double-digit gains.

However, Gilmore won’t be here next year. He’s moving to a school where the ACE turnaround worked: Dade Middle School. It’s in another tough neighborhood, just southeast of downtown.

As for the kids of Edison, they’re moving, too. This fall, they’ll go less than a mile away to Pinkston High School — to a new kind of school within a school.

Next week, we’ll go inside Pinkston High School, as it prepares to absorb another school.