The art class room at L.G. Pinkston High School in Dallas on April 4, 2018. Photo: Lara Solt

The art class room at L.G. Pinkston High School in Dallas on April 4, 2018. Photo: Lara Solt

When Texas Schools Don’t Make The Grade

Every year, Texas schools are given a grade by the Texas Education Agency. A school starts facing consequences as soon as its first year with a failing rating. And the stakes get higher the longer the school stays on the state’s failing list. A 2015 law allows the state to shut down schools that for five straight years get the “Improvement Required” rating. The state could also take over a school district with a failing school.

In this series, “The Race To Save Failing Schools,” KERA is focusing on five North Texas schools — four that have been failing for at least three years and one that was taken off the state’s list after turning things around. Over the next few weeks, we’ll be exploring the effort required to bring a school up to standard and the consequences for failing from the perspectives of students, parents and educators. Stories on each school will be published in weekly installments through the end of May.

Note: This series uses data and accountability information through 2016-17, the most recent school year for which complete state information is available.

How schools are graded

Every year, the Texas Education Agency assigns accountability ratings to schools, indicating whether they meet or fail to meet state standards. The ratings and their criteria have changed over the years, making year-to-year comparisons inexact.

In this series, we’re looking at the pass-fail accountability system used from 2012-13 until last school year (2016-17). In this system, schools earn either a “Met Standard” or “Improvement Required” rating.

Under this system, schools are measured by four performance indexes:

- Student achievement measures district and campus performance based on student achievement (test scores) across all subjects for students.

- Student progress measures progress in English and math by demographic and academic categories, including race and ethnicity, English language proficiency and special education.

- Closing performance gaps measures academic achievement (test scores) of economically disadvantaged students and the two lowest-performing racial/ethnic student groups, which are determined by the previous year’s assessment. The goal is to raise those groups to levels closer to higher-performing peers.

- Postsecondary readiness measures the role of elementary and middle schools in preparing students for high school — and the role of high schools in preparing students for college and work.

To receive a “Met Standard” rating, districts and campuses must meet targets (which vary by type of campus: elementary, middle, charter, etc.) set in three of the four indexes: Index 1 or Index 2 and both Index 3 and 4.

For more details on the state’s accountability system, download Chapters 2 and 3 from the TEA manual. Note: Ratings under the new A-F system will be issued in the fall — read more about that from The Texas Tribune.

Previous accountability system

Many schools featured in this series and across Texas took a turn for the worse in the 2012-13 school year. That was the first year both the new STAAR standardized tests and the four performance indexes were incorporated into the accountability system. Though the tests were actually introduced the previous school year, TEA decided not to assign accountability ratings that year with so many changes.

From 2003 to 2011, the state used a different accountability system with different criteria. Schools and districts were evaluated on students’ performance on the TAKS, attendance rates, high school completion rates, annual dropout rates for grades 7-12 and college readiness. Possible ratings from best to worst were: “Exemplary,” “Recognized,” “Academically Acceptable” and “Academically Unacceptable.”

The consequences of Improvement Required

There are consequences if a school earns the failing grade year after year. House Bill 1842, which passed during the 2015 Texas legislative session, allows the state to strip districts of their authority if they cannot improve their struggling schools.

The law created a new reform process, outlining steps for school districts to take. The action required of the district becomes more intensive each year a campus remains on the state’s failing list.

“It says that when you make five years [“Improvement Required”], the [TEA] commissioner has to either close you or put a board of managers in over the district,” the TEA’s DeEtta Culbertson told KERA.

Graphic: Justin Bowers

However, some schools have stayed on the list longer than five years. This can happen for a variety of reasons, including a reprieve due to a change in TEA’s accountability criteria.

“When this legislation came out, we kind of had to phase it in, so that’s why you’re seeing some of the schools with six and seven years of [Improvement Required] status,” Culbertson said.

Failing Schools In North Texas

This map shows all North Texas schools that have been on the TEA’s failing list for at least three years. We’re focusing on four: John T. White and Mitchell Boulevard elementaries in Fort Worth, Edison Middle Learning Center in Dallas and Wimbish Elementary in Arlington. We’re also looking at Dallas’ Pinkston High School, which is no longer on the list.

Click on the markers to see information about the schools. Colors represent how long a school has been on the list. Note: Student population and accountability (years on the Improvement Required list) reflect the 2016-17 school year.

Map credit: Justin Bowers

Schools In The Series

Leadership Academy At John T. White Elementary, Fort Worth

John T. White Elementary School in Fort Worth on April 20, 2018. Photo: Lara Solt

Note: Most recent data available on schools are from 2016-17, which was the last school year the state’s pass-fail accountability system was used. Ratings under the new A-F system will be issued in the fall.

Opened in 2011 to relieve crowding at other nearby schools, John T. White in northeast Fort Worth has always been on the state’s failing list. The district declined to let KERA report from inside the school, saying administrators were focused on improvements at the school.

With the hopes of improving its rating, Fort Worth ISD this school year designated John T. White as one of its leadership academies. Among other changes, the program brings in highly rated educators, extends the school day and serves kids three meals a day.

The school stands out for having the highest mobility rate (40.2 percent in 2015-16) among the five schools in this series. That means nearly 300 students weren’t there for six weeks or more in the school year. And since the school opened, many are considered economically disadvantaged .

Like the other schools featured in this series, White has a high percentage of at-risk students. That population jumped from 26 percent in 2012-13 to 74 percent last school year. That’s the largest increase in that time period among the five schools.

Nearly three-quarters of students are black and more than 20 percent are Hispanic. However, the percentage of black teachers has sharply declined in recent years — from nearly 64 percent in 2012-13 to just under 30 percent last school year. The percentages of white and Hispanic teachers have both doubled in that same time. Nearly half of the faculty is white. Most teachers have no more than five years of classroom experience.

White has exceptionally low STAAR test passing rates. Last year, less than half of fifth-graders passed the math assessment, and 55 percent passed reading. For comparison, 87 percent of fifth-graders across the state passed math last year, and 82 percent passed reading. Those low test scores contributed to White’s failing rating last year.

Graphic: Molly Evans

More about John T. White

- John T. White by the numbers

- Explore the Northeast Fort Worth neighborhood

- KERA’s conversation on John T. White

- Full 2016-17 TAPR report for John T. White

- 2016-17 accountability summary for John T. White

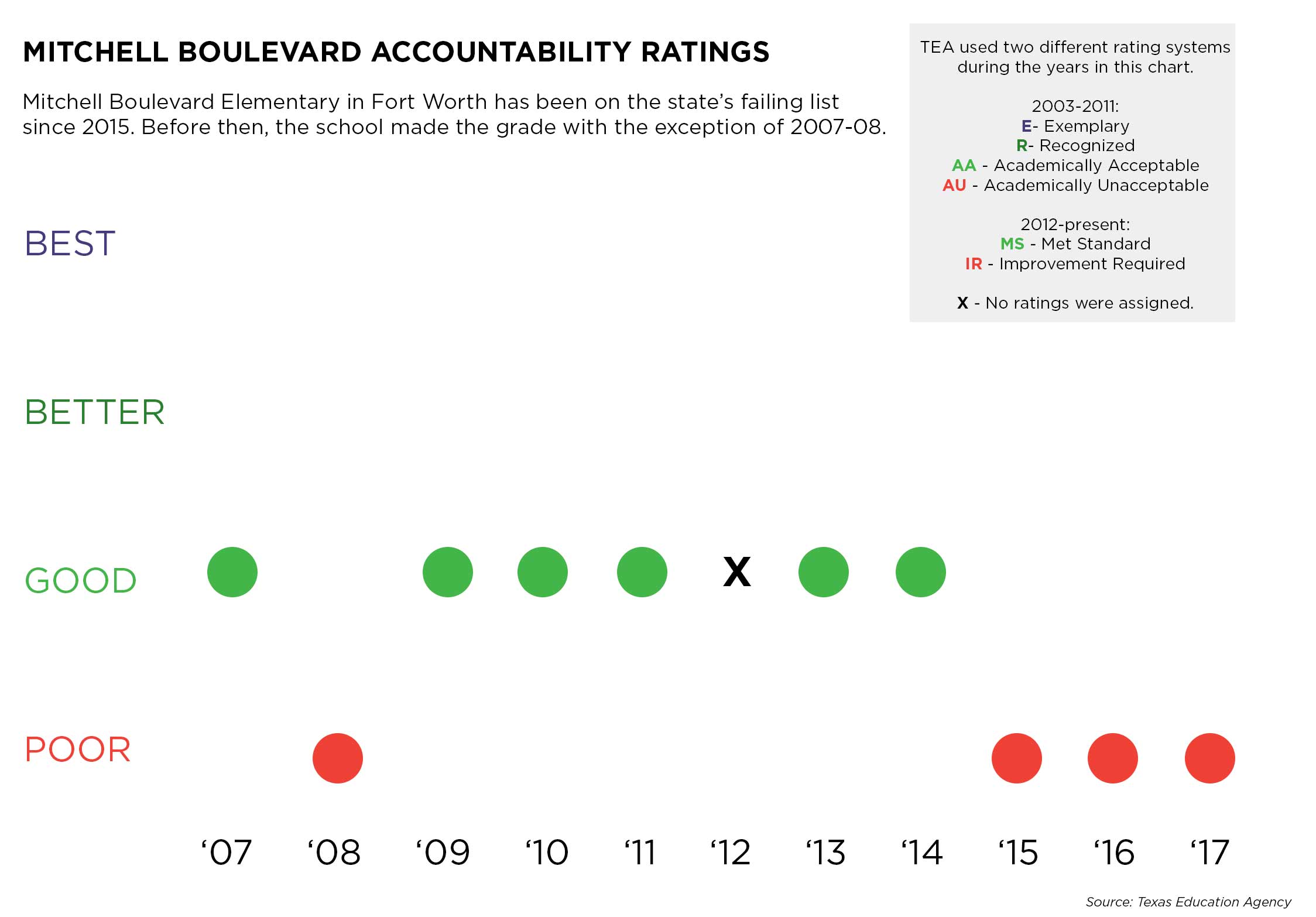

Leadership Academy At Mitchell Boulevard Elementary, Fort Worth

Mitchell Boulevard Elementary School in Fort Worth on April 3, 2018. Photo: Lara Solt

Note: Most recent data available on schools are from 2016-17, which was the last school year the state’s pass-fail accountability system was used. Ratings under the new A-F system will be issued in the fall.

Like John T. White, Mitchell Boulevard is one of five struggling schools in the Fort Worth school district that’s been turned into a leadership academy this school year. Despite being rated “Improvement Required” for three years in a row, school leaders and teachers are energized, focused on overcoming challenges and earning a passing grade.

Principal Aileen Martina says one of the challenges the school faces is the number of students who move around. The school serves many children in nearby apartments, and that contributes to its high mobility rate. In 2015-16, the mobility rate at Mitchell Boulevard was 33 percent, meaning nearly 130 kids weren’t there for six weeks or more out of the school year.

“Every day we enroll and we withdraw one or two students — it’s every day. So that’s a big challenge,” Martina told KERA.

Mitchell Boulevard has seen a big increase in at-risk students, jumping from almost 33 percent percent of students in 2012-13 to 72 percent the last school year.

The majority of teachers and students are black at the Southeast Fort Worth school, but both have decreased in recent years. Meanwhile, the percentages of Hispanic students and teachers have increased. The percentage of white teachers has dropped from 34 percent to 17 percent over the past 10 years.

Teachers with no more than five years of experience made up 72 percent of the school last school year. The average experience of teachers dropped from 10 years to four in a decade.

Mitchell Boulevard has seen a large jump in the passing rate for fifth-graders on the annual math test: 85 percent passed last school year versus 56 percent in 2012-13. Reading passing rates, however, have suffered: 63 percent passed last year, down from 73 percent in 2012-13. Test performance contributed to the school’s failing rating last year.

Graphic: Molly Evans

More about Mitchell Boulevard

- Mitchell Boulevard by the numbers

- Explore the southeast Fort Worth neighborhood

- KERA’s feature story on Mitchell Boulevard

- Full 2016-17 TAPR report for Mitchell Boulevard

- 2016-17 accountability summary for Mitchell Boulevard

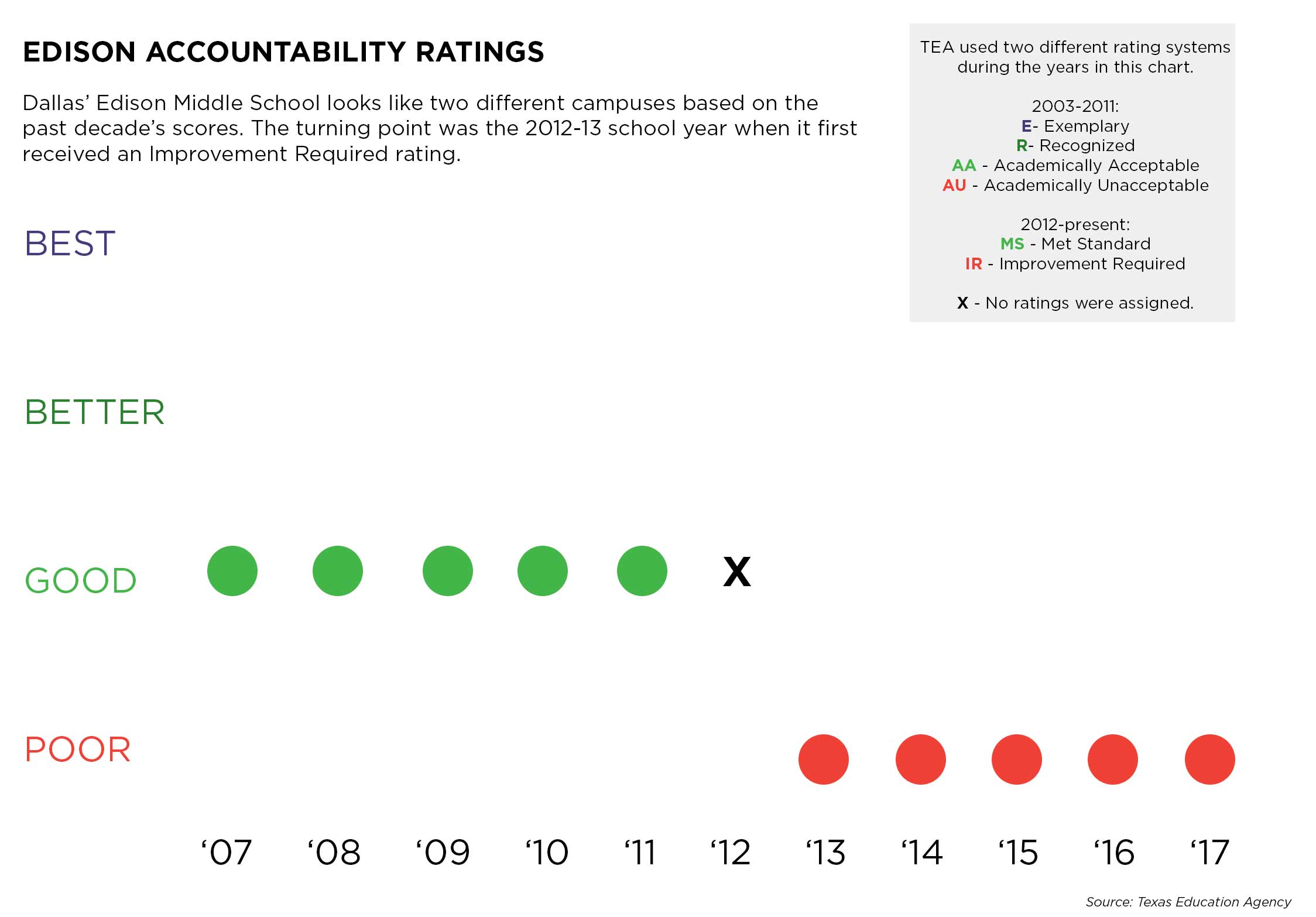

Thomas A. Edison Middle Learning Center, Dallas

Thomas A. Edison Middle Learning Center in Dallas on March 28, 2018. Photo: Lara Solt

Note: Most recent data available on schools are from 2016-17, which was the last school year the state’s pass-fail accountability system was used. Ratings under the new A-F system will be issued in the fall.

In January, the Dallas school board voted to close Edison Middle Learning Center and consolidate it with nearby Pinkston High School in West Dallas. Winding down a school is no easy prospect, and parents and students will have to brace for change come next fall.

The district poured resources into Edison by converting it into one of seven initial ACE schools in 2015. Six of those struggling schools have since earned a “Met Standard” rating. Edison, however, has not left its spot on the “Improvement Required” list for five consecutive years.

Having new leadership in the first year of the ACE program is one reason Edison didn’t progress along with the other schools, according to the district.

Principal Earl Gilmore, who’s now been at Edison two years, told KERA he spent more time on establishing structure and discipline when he first arrived at the school.

“Those things were not here,” he said.

He said if he could go back to his first year, he would have spent more time on teaching students what they needed to pass the state standardized tests. Gilmore has since shifted the focus from discipline to instruction and he said significant progress has been made.

Edison has one of the highest percentages (91 percent in 2016-17) of economically disadvantaged students — second only to Pinkston — and the highest percentage (85.2 percent in 2016-17) of at-risk students among the five schools in this series. But it’s been worse. In 2013-14, 100 percent of students were considered economically disadvantaged.

Edison’s student body is majority Hispanic (57 percent as of last year). The percentage of Hispanic teachers is growing, but still stood at only about 8 percent last year. The Hispanic student population has dropped in recent years, while the percentage of black students has increased to make up nearly 40 percent of the school in 2016-17. The percentage of black teachers has decreased over the past 10 years, but still makes up the majority of the faculty. White teachers make up one-third.

Many of Edison’s teachers are early into their careers; nearly 68 percent of teachers last school year had between zero and five years of experience.

Last year, 76 percent of eighth-graders passed the math assessment, up from 51 percent in 2012-13, when STAAR was first included in the accountability ratings. In that same time period, reading performance slipped from 67 percent of eighth-graders passing to 61 percent last year. The latest passing rates contributed to Edison’s “Improvement Required” rating last year.

Graphic: Molly Evans

More about Edison

- Edison by the numbers

- Explore the West Dallas neighborhood

- KERA’s feature on Edison

- Full 2016-17 TAPR report for Edison

- 2016-17 accountability summary for Edison

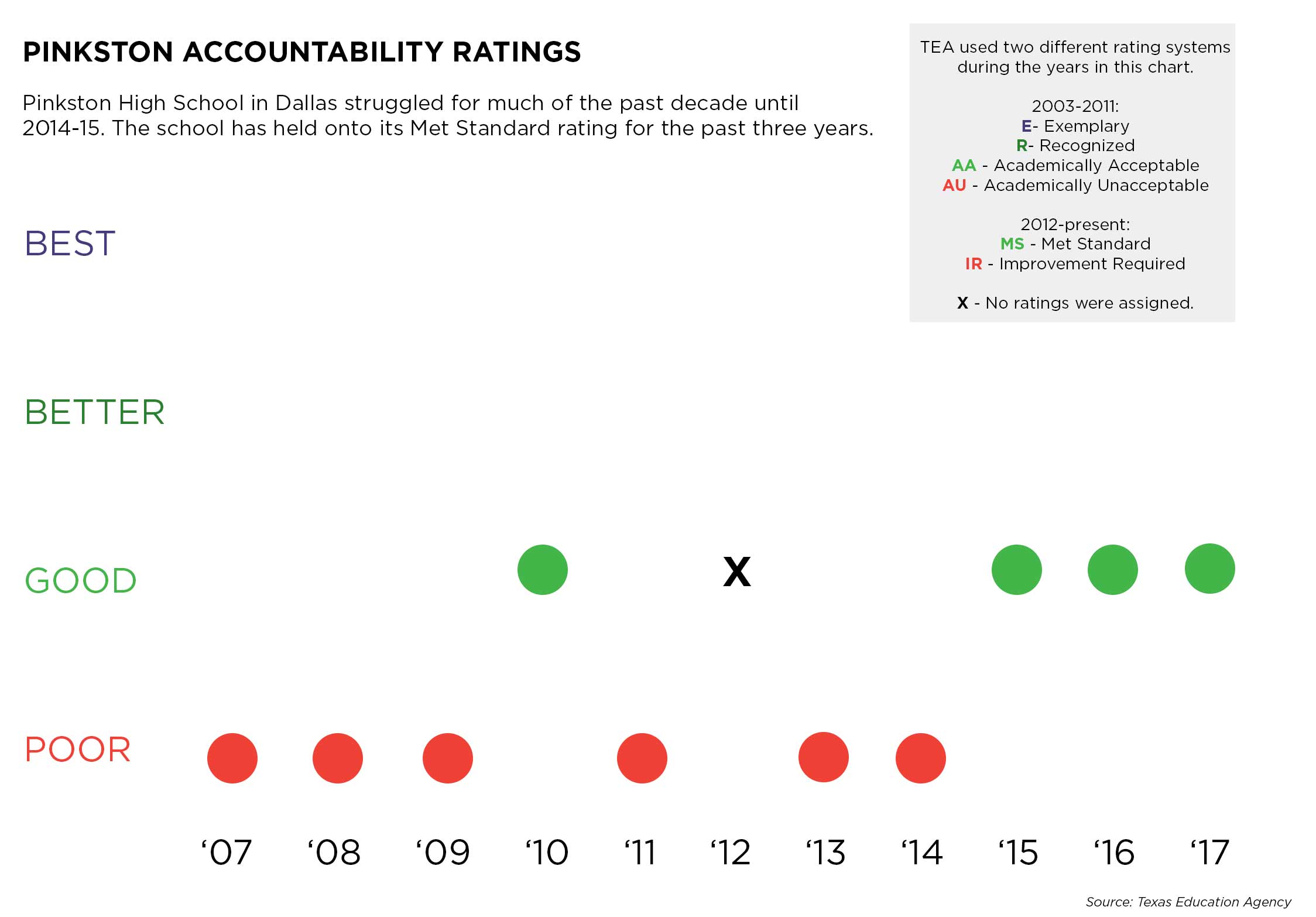

L.G. Pinkston High School, Dallas

L.G. Pinkston High School in Dallas on April 4, 2018. Photo: Lara Solt

Note: Most recent data available on schools are from 2016-17, which was the last school year the state’s pass-fail accountability system was used. Ratings under the new A-F system will be issued in the fall.

Once on the state’s list of failing schools, Pinkston has managed to turn things around. It’s been off the failing list three straight years. Now, with the nearby Edison Middle Learning Center closing, Pinkston is expecting hundreds of new kids and adding seventh and eighth grades. Parents worry that absorbing a failing school could put Pinkston back on the list. And some Edison families question sending middle-schoolers to a campus with older students.

The number of poor students at Pinkston has grown in recent years. The percentage of economically disadvantaged students has jumped from 76 percent in the 2006-07 school year to 92 percent last school year, which largest percentage among the five schools featured in this series.

While the Hispanic student population has grown, the percentage of black students has decreased in recent years. The percentage of Hispanic teachers has risen and the percentage of black teachers and white teachers has dropped. Just over half of the faculty has five years of classroom experience or less.

Between 2012-13 and last school year, the overall passing rate for the Algebra I test jumped 31 percentage points; 76 percent of students passed last year, which is just a few points shy from the state average. English I passing rates, however, didn’t follow suit. Last school year, just 51 percent of Pinkston students passed that test. Statewide, it was 64 percent.

Graphic: Molly Evans

More about Pinkston

- Pinkston by the numbers

- Explore the West Dallas neighborhood

- KERA’s feature on Pinkston

- Full 2016-17 TAPR report for Pinkston

- 2016-17 accountability summary for Pinkston

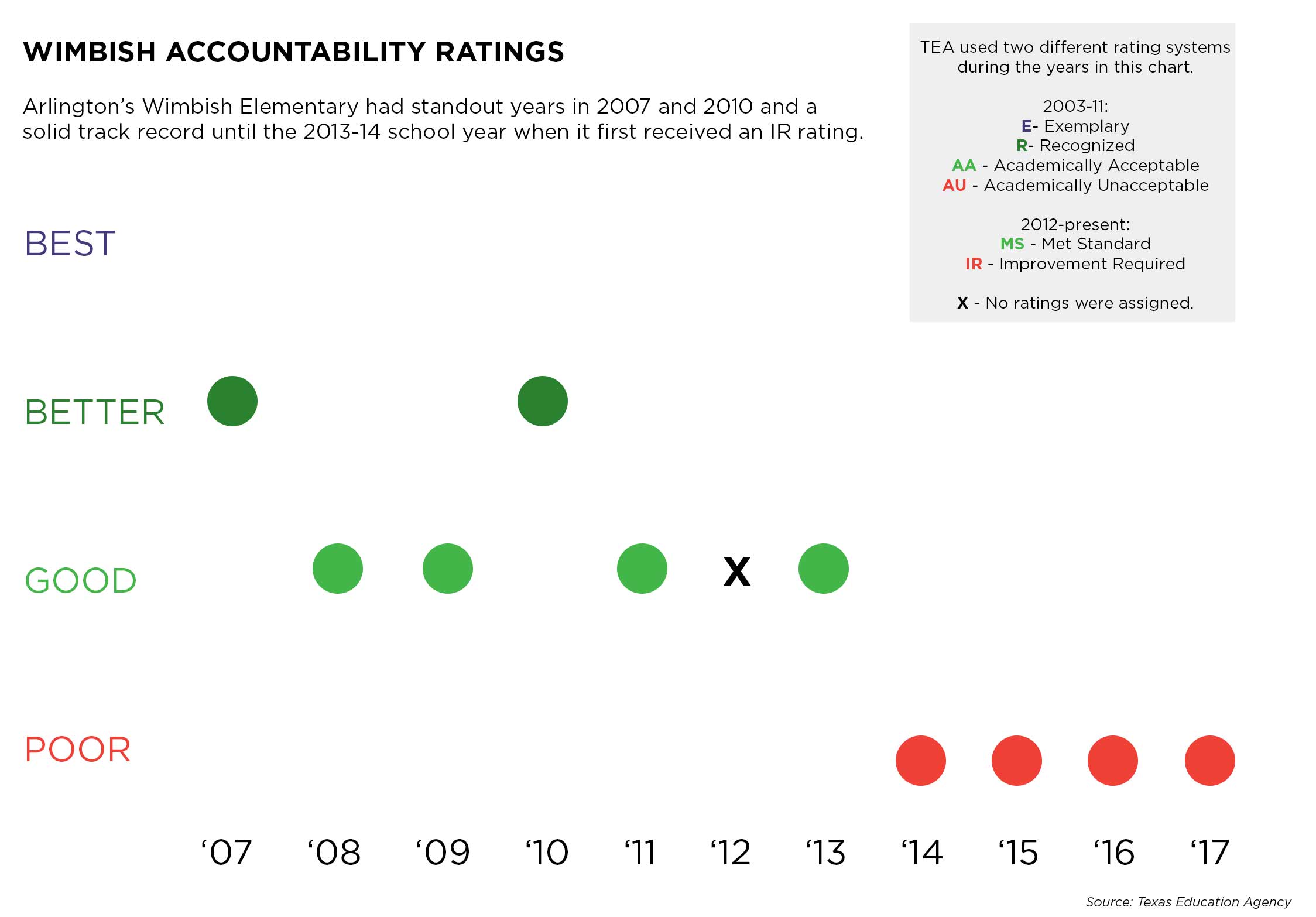

Wimbish Elementary, Arlington

Wimbish Elementary School in Arlington on April 20, 2018. Photo: Lara Solt

Note: Most recent data available on schools are from 2016-17, which was the last school year the state’s pass-fail accountability system was used. Ratings under the new A-F system will be issued in the fall.

Amid prosperous suburban neighborhoods and gleaming sports stadiums, Arlington has schools that face issues more typical in urban districts. Wimbish was labeled a “Recognized” school as recently as 2010. It’s now been on the state’s failing list for four years in a row.

As of the last school year, black students, the largest and fastest-growing racial demographic at the school, made up 47 percent of the Wimbish student body. There were no black teachers 10 years ago; now, they make up 20 percent of faculty. Hispanic students make up a third of the school, but less than 10 percent of teachers are Hispanic.

Just over 45 percent of the faculty has between zero and five years of classroom experience. The next largest group (almost 30 percent) has between 11 and 20 years. More beginning teachers have come to the school over the past decade.

The at-risk student population has jumped from just over half of the school to 71 percent over the past 10 years. Wimbish has the lowest percentage of economically disadvantaged students in the series — they account for 84 percent of the school.

The school didn’t meet its own goals last year in student achievement or closing performance gaps, earning it an “Improvement Required” rating. Seventy-two percent of fifth-graders passed the math test; 62 percent passed the reading assessment.

Graphic: Molly Evans

More about Wimbish

- Wimbish by the numbers

- Explore the north Arlington neighborhood

- KERA’s feature story on Wimbish

- Full 2016-17 TAPR report for Wimbish

- 2016-17 accountability summary for Wimbish

Research conducted by Kit Lively. Information gathered from Texas Education Agency data.

This post was updated May 11 to reflect that Pinkston will only absorb seventh and eighth-graders from Edison, not sixth grade.