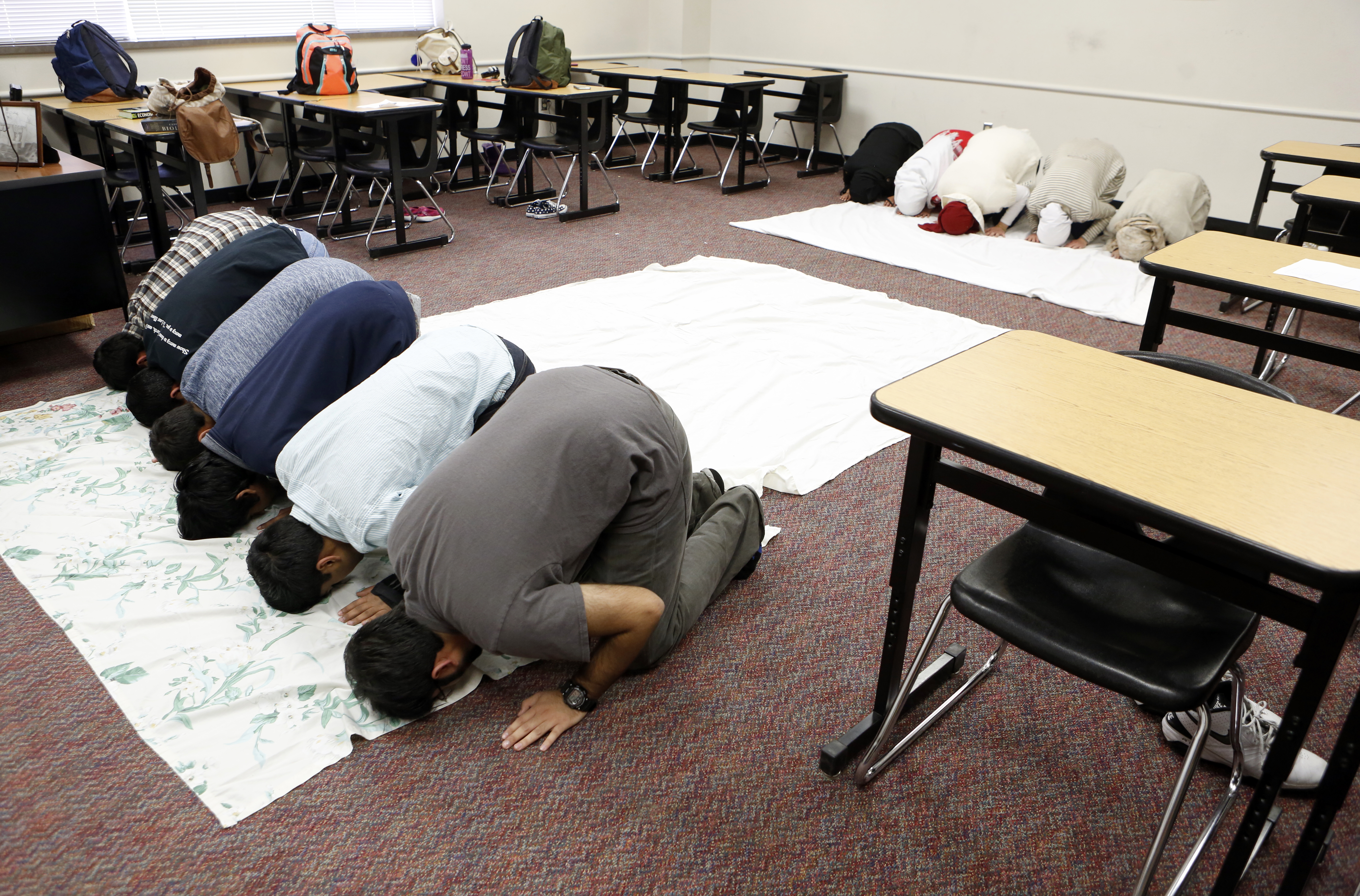

Amna Salman (foreground) and other Muslim students gather to pray inside a classroom at Liberty High in Frisco. Photo/Lara Solt

Amna Salman (foreground) and other Muslim students gather to pray inside a classroom at Liberty High in Frisco. Photo/Lara Solt

From Its Prayer Room To Podcasts, Liberty High Shatters Stereotypes

The city of Frisco has transformed over the last quarter century – from a country town to a booming suburb that’s home to high-end shops and the Dallas Cowboys. Its schools have been transformed, too. Here’s a look at how one school — Liberty High — is changing.

It’s a Friday afternoon, a little after 2, at Liberty High School. Student Zaki Sayyid recites the Islamic call to prayer. He and 10 other Muslim students are inside a classroom, on their knees facing east.

Girls wear hijabs. Everyone’s taken off their shoes. They spend the next 15 minutes in prayer.

This isn’t a common scene at most schools. But at Liberty, it happens every Friday.

Frisco, once a small, railroad town, is now one of the fastest-growing cities in the country. Two decades ago, three out of every four people living in Frisco were white. Today, it’s a fusion of races and ethnicities.

And the schools are a microcosm of the city. At Liberty, less than half of the students are white, while 30 percent are Asian.

Students crowd the hallway after the last bell rings at Liberty High School in Frisco. Photo/Lara Solt

Embracing Tradition, Exploring Cultures

Divya Murali is a junior at Liberty. She was born in Mesquite. Her parents are from the Southern Indian state of Tamil Nadu, known for its majestic Hindu temples.

Even though she was born in North Texas, Murali embraces her Indian roots. She celebrates Diwali and goes to the Hindu version of Sunday school.

But when it comes to Tamil, the language spoken in southern India, it was hard for her to adopt.

“When I was younger, like in elementary school, my parents took me to like a Tamil school that they had running here, and I hated it,” she said. “I can understand Tamil, but my American accent is so strong, you can’t really understand my Tamil.”

Journalism student Divya Murali talks to teacher Brian Higgins about her weekly podcast. Photo/Lara Solt

She’s also learned some Hindi. This cultural curiosity is what fuels her — and the weekly podcast she produces.

“Hey there, Redhawks, I’m Divya Murali and this is the 19th episode of the United Colors of Liberty, and today I’m here with senior Lizzie …”

Every week, Murali has an in-depth conversation with a different Liberty student. There’s an Indian student who’s Christian, a kid who’s a lesbian with interracial parents and a black student who doesn’t celebrate Kwanzaa.

Sometimes current headlines spark an idea. Like when she interviewed a Russian-born classmate.

“How do you feel about there may potentially be more of an intense hostility between the countries?”

“I don’t think it would get to the same point it was at the Cold War…”

Lately, Murali’s been thinking about the shooting of two Indian men in suburban Kansas in February. One was killed. The accused shooter is white. Before he was arrested, he said he thought they were Middle Eastern.

“What happened in Kansas was truly a tragedy, especially since the Indian man and his friend that were killed, that could have easily been one of my relatives — my dad, someone close to me,” she said.

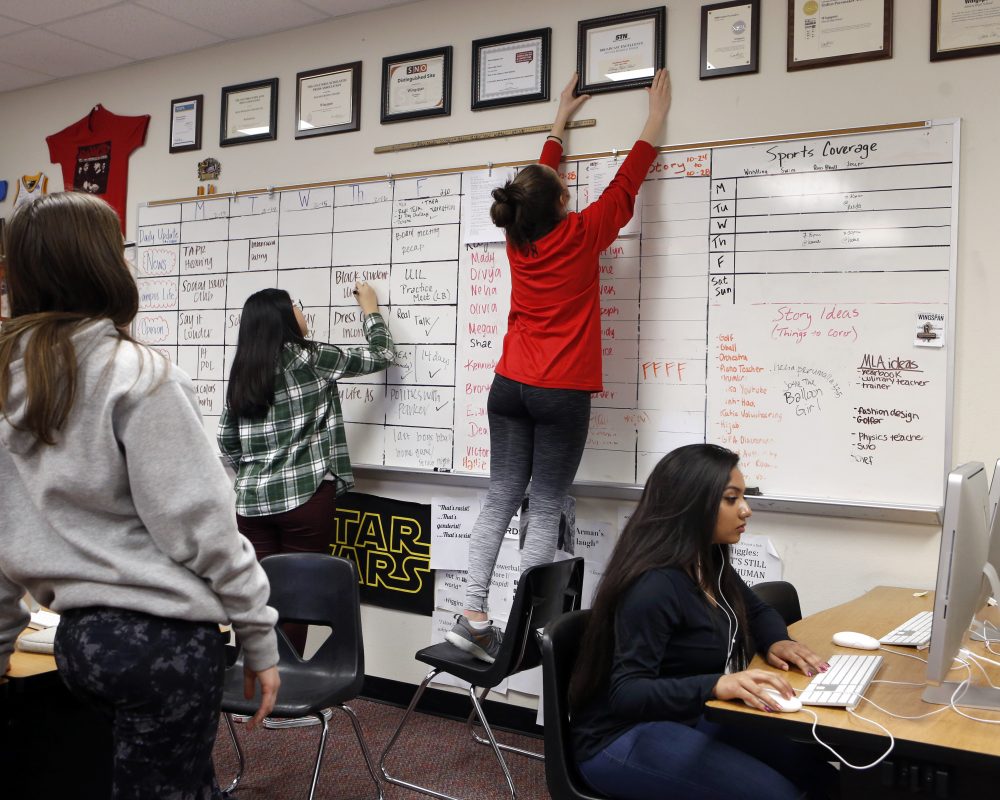

Megan Lin updates the storyboard for the student news site, Wingspan. Photo/Lara Solt

Accommodating A Changing Student Body

Brian Higgins teaches journalism to Murali and her classmates.

“Hopefully, they’re hearing something that they maybe never thought of before,” he said. “And if we can get one student to think differently or to perhaps better understand the diversity and the different people and their backgrounds on this campus, then I think we’ve done a good job.”

Higgins came from a different school — Lovejoy — that’s affluent and about 85 percent white. He says being in a more diverse school gives kids the chance to explore a more challenging range of issues.

Take Megan Lin. She’s Chinese, a sophomore and just wrote a column about Asian stereotypes. She says it bugs her when people assume all Asian students are over-achievers.

“Some people think it’s a good stereotype to be stereotyped as a smart person,” Lin said. “But for those people when they’re expected to be smart and they feel inadequate, they feel like they’re a shame to their culture and I don’t think that’s right.”

Sometimes, changes in a student body forces a school to change, too.

Before 2009, there was no prayer room at Liberty.

Prinicipal Scott Warstler noticed back then that Muslim students at Liberty were leaving school on Fridays for prayer.

Liberty High School Principal Scott Warstler. Photo/Stella M. Chávez

“Parents would come pick them up,” he said. “What we found was they were missing about two hours of class because of the commute.”

At one point, 30 students were leaving campus to pray at a Plano mosque. Eventually, Liberty let them use an empty classroom as a prayer room.

So far, Warstler says, they haven’t gotten any pushback.

“They’re not out proselytizing,” he said. “They’re not out in the lunch periods trying to gain, you know. They take care of themselves in their group and they accept those that are a part of their group. And honestly, if others wanted to go in and learn and see and experience that, they’re OK with that.”

More: Read Liberty High’s story on the prayer room in Wingspan, a student publication.

Muslim students gather to pray inside a classroom at Liberty High. Photo/Lara Solt

Earning Respect By Showing Respect

Learning more about each other was the point last year when then-senior Jay Schlaegel organized a forum on religious diversity at Liberty.

He’s now a freshman at Texas A&M. At the time, Schlaegel was president of Liberty’s Bible study group. And that night, he shared the stage with presidents of the Muslims and Hindu student associations.

Jay Schlaegal is graduate of Liberty High. Photo/Stella M. Chávez

He organized the event after hearing comments about Muslims and Hindus that bothered him.

“With Islamic radicalism around the globe, you have people in Frisco, Texas, that are being talked about in ways that…it’s an unrelated thing,” Schlaegel said. “And I can’t agree with that. I think that that’s complete lack of understanding, like an ignorance of people that you’ve been neighbors with for years.”

At the forum, Schlaegel and the other students explained what their religions are about – and took questions from the audience. He says fostering these kind of conversations are crucial.

“As a believer in Christ, I want my faith respected,” he said. “If I want that respect, if we want respect as people, then we need to show respect.”

And on that Friday afternoon at Liberty, Shoaib Farooqui leads other Muslim students in prayer.

“Brothers and sisters of Islam, I’m sure we all have at one point been told to count our blessings. We live in suburban houses. We have eaten…”

The 16-year-old says he feels a sense of responsibility to explain what Islam is and what it’s not.

“And then hopefully, people from quote ‘the Western World’ will be able to say, ‘Hey, you guys aren’t exactly like ISIS,” Farooqui says. “You guys aren’t exactly like terror groups. You aren’t exactly supporting an oppressive nation. And hopefully, that can sort of alter the perception we see today.”

Update: Prayer Room Raises Concerns

The classroom used as a prayer room got the attention of the Texas attorney general’s office. The office sent a letter to the Frisco school district raising constitutional concerns about the room. The Frisco superintendent called the letter a “publicity stunt” and said the prayer room has been in use for several years without complaints.

Tim Boyer was so unhappy about the prayer room at Liberty High that he went to a recent Frisco school board meeting and spoke his mind.

“Liberty High School is not a mosque. It’s not a synagogue. It’s not a tabernacle. It’s not a temple. It’s not a church,” Boyer said. “It is a school. It is a public school supported by taxpayers for the purpose of educating our children.”

The Frisco Independent School District has said it didn’t violate any state or federal laws by having a prayer room and that the room is open to students of all faiths.

Marc Rylander, director of communications for the attorney general’s office, issued a statement, saying the office had been in contact with school district attorneys.

“They assured us … that students of all faith, or no faith, may now use this meeting room during non-instructional time on a first-come, first-served basis for student-led activities,” the statement said. “Religious liberty is a cornerstone of our society and we are glad that students at Frisco ISD may practice their faith in accordance with their beliefs.”

It’s not clear how many public schools in Texas have prayer rooms or designated areas where students can pray, but they are in some schools across the state and country.

“You may hear it said sometimes that prayer’s been kicked out of public schools,” said Joy Baskin, director of legal services with the Texas Association of School Boards. “In fact, what has been determined by the courts is that schools can’t compel prayer.”

Baskin said prayer rooms in schools are acceptable and legal under the First Amendment. Schools can also give students time to pray, whether it’s during free time or a lunch period. They can give students passes to leave class to pray or leave campus for religious education.

Student Voices On Race

Students talked to KERA about their experiences with race in and out of school. We start with Rida Iqbal who wears a hijab and is president of the Muslim Student Association.