A knight, given to the school by the first graduating class, stands in the lobby at Kimball High in Dallas. Photo/Lara Solt

A knight, given to the school by the first graduating class, stands in the lobby at Kimball High in Dallas. Photo/Lara Solt

Over 50 Years, Kimball Transforms Again And Again

Kimball High School in Dallas has endured a demographic shift over the past 50 years. First came integration, then busing and white flight, followed by waves of immigration, economic troubles and competition from charter and private schools. Again and again, the educational landscape has been reshaped — and so has the Oak Cliff neighborhood of southern Dallas.

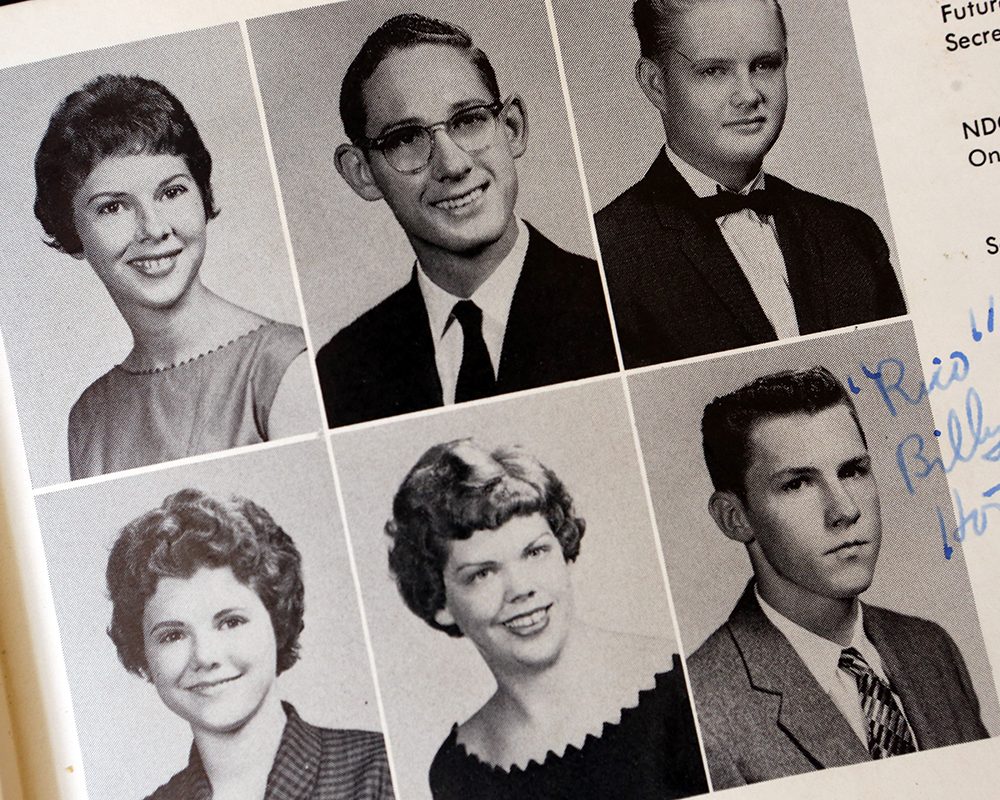

The Early Days Of Kimball High

It was 1961, just three years since Kimball High School in Dallas opened. Margie Horton was among the first students to walk Kimball’s halls. She was Margie Holman at the time — and part of the school’s second graduating class.

“It was wonderful, it was exciting. It was brand new,” she recalls. “We got to choose the mascot, the name of the drill team. So we had lots of activities going on.”

When Horton graduated, Kimball had 1,400 students, about the same number as today. Back then, Kimball included seventh and eighth grades because the middle school wasn’t built yet.

Nearly every student was white. Horton’s classmates called themselves the Knights.

“Because it was Justin F. Kimball and so we thought J.F.K. and “K” would be the Knights.”

Even in those early years, race rippled through this Oak Cliff Camelot, recalls Steve Bartlett, class of ‘66. Bartlett, who would become a Congressman and the mayor of Dallas, was prepping for a debate tournament.

“We got the word from the school district that the Jesuit team from North Dallas had been disinvited because the team had an African-American debater,” Bartlett said. “I made probably the most passionate speech of my high school career on the debate squad to convince the Kimball debate squad to boycott the tournament.”

Bartlett, offended by the racism, says the district didn’t go for his boycott, and only he stayed behind.

“So those were the kind of times we were in,” he recalled. “There was this constant struggle. The adults knew that they needed to integrate and didn’t know how … [they] were trying to avoid it.”

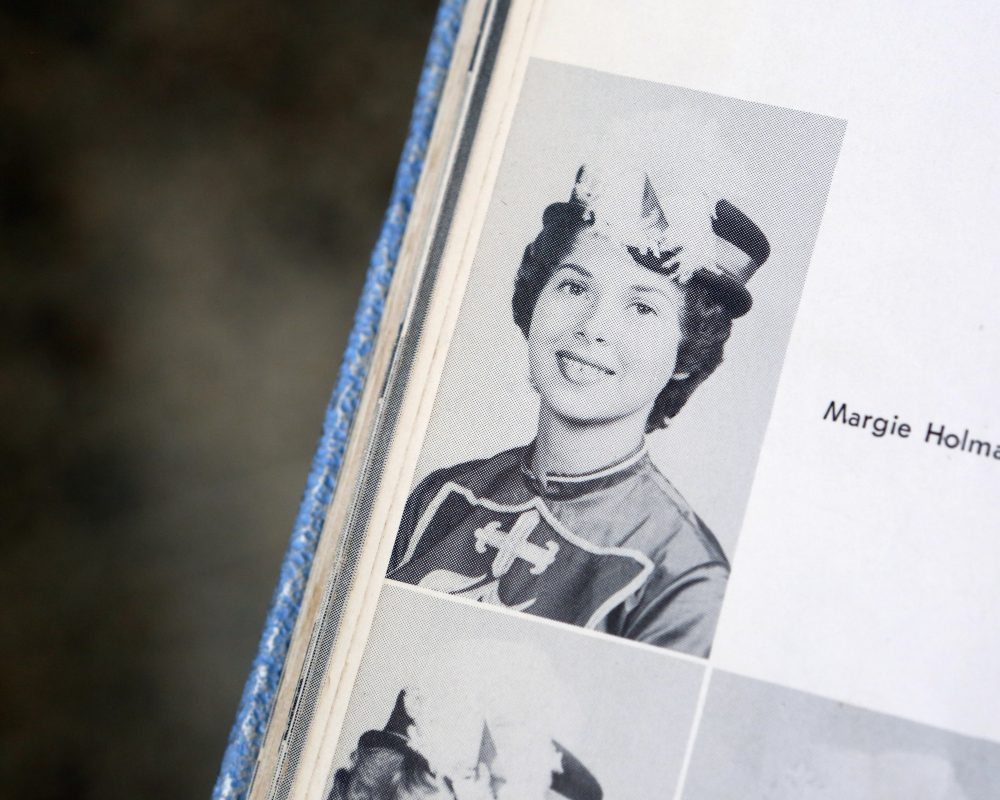

The drill team with Margie Holman Horton pictured on the far left in her school yearbook. Photo/Lara Solt

The District Desegregates

It was 1971. Courts ordered the Dallas school district to desegregate. It took five years before busing began. Future Kimball graduate Debbie Cox was 8.

“Our neighbors that lived immediately, directly across the street from us … the year they started in busing, boy, the for-sale sign went up in their yard, and they booked it up north to Richardson,” Cox recalls.

She says most of her white neighbors moved south to growing suburbs like Duncanville or DeSoto. In 1977, D Magazine reported that a wealthy northwest subdistrict of Dallas lost a third of its white students. Over a seven-year period, more than 40,000 white kids left district-wide.

African Americans now made up almost half the Dallas student population. In 1983, Cox, who’s white, entered a racially mixed Kimball High.

“We all got along,” she said. “I have to say, [I] kind of credit part of who my character is, was from growing up with all those different cultures. You learn to get along and I think we were all struggling to get by and to help each other out.”

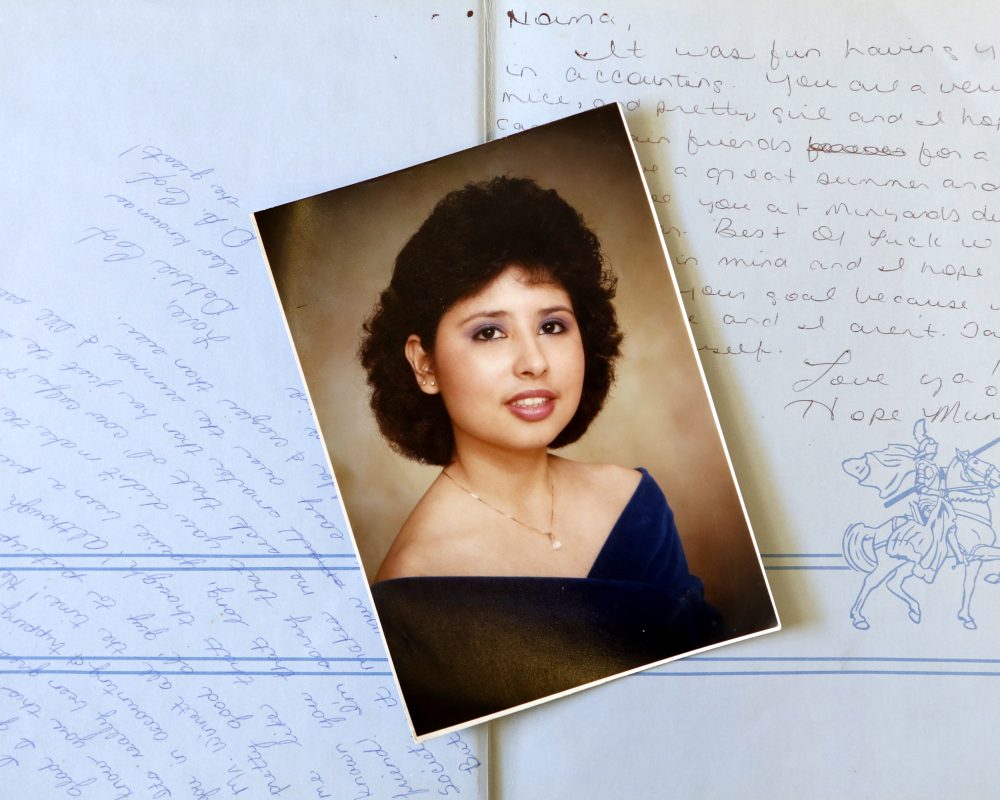

When Norma Valdez Aragon – also the class of ’86 — was little, her family moved to Dallas from Mexico. There were no bilingual classes then. Learning English was sink or swim.She swam. By high school, Aragon says no one knew English was her second language. She felt welcomed at Kimball.

“I had a great educational experience. I really believe that’s why I became a teacher,” she said. “It’s not talked about but I felt teachers were culturally responsive to the needs of students. Even as far back as when I was in school.”

Kimball Struggles Academically

Aragon started as a social studies teacher and is now an instructional coach at Kimball. Her kids attend the school. One even just started teaching there. She’s seen a dramatic change at the school – from majority black to majority Hispanic – and in the neighborhood.

Her 1986 classmate, Yvonne Perez Shaw, said it looks different.

“Wasn’t taken care of. It makes me sad. I love the area,” she said. “But I think that comes with respect. Respecting your house, how you take care of things. But it’s a different time. That neighborhood, it’s the whole neighborhood.”

In time, the school suffered, too. Beginning in 2006, the state rated Kimball academically unacceptable. It stayed that way for five of the next six years.

DeEtta Culbertson with the Texas Education Agency puts that academically unacceptable — or AU — rating in perspective.

“In 2009, [Kimball was] what we call a four-year AU school,” she said. “And they were one of eight campuses out of almost 6,000 that were low performing that year.”

Only eight out of 6,000 schools. In the entire state.

Graphic/Molly Evans

Photo/Lara Solt

Many Students Know Poverty Well

Phillip Tanner graduated from Kimball in 2006, the first of those five academically unacceptable years. His family was like many at Kimball – black and low-income. That year, African-American students were the majority at Kimball.

Tanner says he ran the streets with friends from his apartment building. He also ran for Kimball’s football team, becoming an all-district running back. That got him into college. Then he signed with the Dallas Cowboys for three years. Now he’s got a new career — coaching at Kimball.

“It’s definitely a different generation of kids,” he said. “They need the support. We had the support from mom and the staff. However, some of these kids don’t have the support from family and barely get it from staff.”

Tanner came back to change that — as did some fellow Kimball graduates.

“Just seeing how the kids’ face light up to know, ‘Oh he’s a professional ballplayer. And he came from the same streets I came from, sat in the same desk I came in,'” Tanner said. “Knowledge is so powerful and it’s everlasting.

“I could definitely write a check for jerseys. Jerseys get too small; shoes will get too small. However, knowledge can be passed on and on and on, and it’s only right I come back and do the same thing that was done for me.”

Kimball’s changed yet again.

Today, Kimball has changed yet again. Two of every three students are Hispanic. The other third are mostly black. There’s only a handful of white kids.

Kimball is working hard to rebound academically. Despite a wave of new charter schools and competition from nearby districts, the school has consistently met tougher academic standards. And in the state’s new school-grading system, which doesn’t officially take effect until 2018, Kimball hasn’t received a single “F.”

Big barriers remain, however. Like poverty. When Phillip Tanner was a sophomore, 57 percent of the students were economically disadvantaged. Today it’s 83 percent.