Jude Cobler at All Saints Catholic School in Far North Dallas. Photo/Christina Ulsh

Jude Cobler at All Saints Catholic School in Far North Dallas. Photo/Christina Ulsh

Cancer Diagnosis Won’t Steal This Boy’s Spirit

First came the strange lumpy bruises and high fevers. Then a trip to the hospital. Finally, a diagnosis: cancer. Doctors did everything they could to save Jude Cobler, just a kindergartener. But chemotherapy and radiation have a long-term price.

Jude Cobler is a student at All Saints Catholic School in Far North Dallas. Photo/Christina Ulsh

From time to time, Jude Cobler’s classmates ask him about cancer. When he was 5 years old, some were worried they’d catch it.

Jude Cobler, left, eats lunch with classmates at All Saints Catholic School in Far North Dallas. Photo/Christina Ulsh

“They ask me: ‘How do you get cancer?’ And I said: ‘You don’t. You just have to be really unlucky.’”

Jude laughs.

Lucky or unlucky, Jude is a popular kid. Now 10, the Plano boy has glossy dark hair that falls over his round face. At lunch one day, packing spaghetti and meatballs onto a spork, he’s surrounded by friends at All Saints Catholic School in Far North Dallas.

His buddy, Mannie Greichi, says what draws kids to Jude aren’t just his jokes.

“It’s because of what he’s been through,” Mannie says.

“I wasn’t even sure what leukemia was,” said Keith Cobler, Jude’s father. Photo/Christina Ulsh

“He’s really nice and he shares.”

Jude’s story begins five years ago, during the first week of kindergarten. Jude had several high fevers. Strange lumpy bruises appeared on his legs. The bruises didn’t look normal.

Jude’s parents rushed him to Children’s Medical Center at Legacy in Plano.

“The doctor said, ‘Best case: It’s some type of bacterial, viral infection,’” said Jude’s dad, Keith Cobler. “Worst case: It’s leukemia. … I wasn’t even sure what leukemia was.”

Just 15 minutes later, the bloodwork was back, the diagnosis in.

Jude Cobler during one of his hospital stays at Children’s Medical Center. Photo/Courtesy Cobler family

Aggressive Cancer, Intensive Treatment

“My parents were crying,” Jude recalled.

“They said, ‘You have leukemia.’ I’m like, ‘What’s that?’ Hopefully, it’s not something bad.”

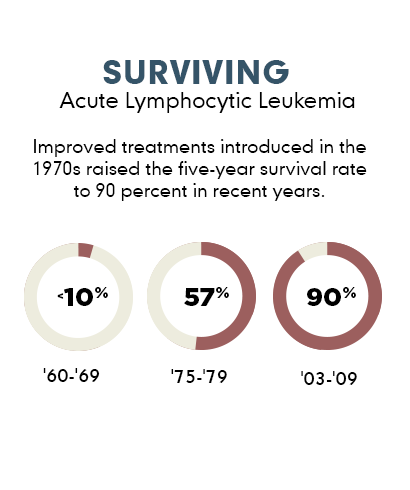

Just a half century ago, a leukemia diagnosis was a death sentence for kids. The disease starts when the bone marrow creates abnormal white blood cells that divide out of control. These defective cells crowd out healthy ones, making it hard for the body to fight infection and damaging vital organs.

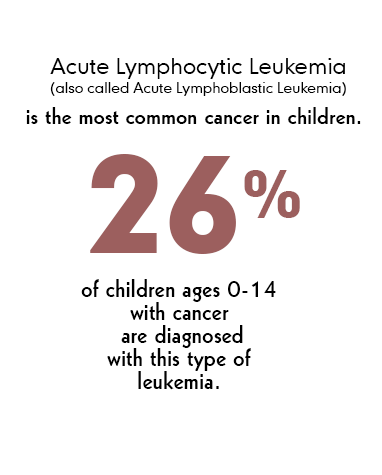

The type Jude had – Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia or ALL — shows up in about 2,500 children each year.

Source: Cancer.org

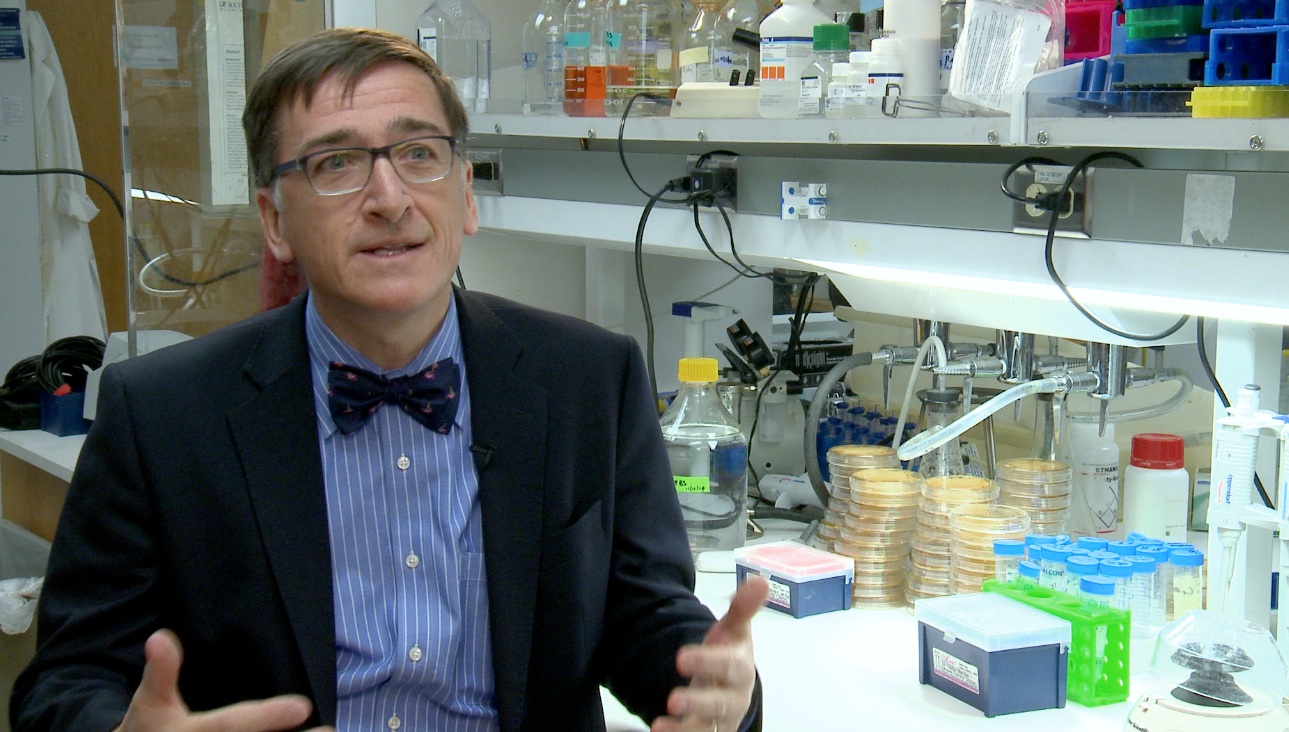

Jude’s doctor is Patrick Leavey with UT Southwestern and Children’s Medical Center in Dallas.

“The treatment for ALL is chemotherapy by and large,” Leavey said. “Chemotherapy means giving medications, several all at the same time, to essentially kill the leukemia cells.”

And that’s not all it kills. Chemotherapy wipes out healthy cells, too – like hair, nails and intestinal cells.

Some chemotherapy drugs are taken as pills or through IVs. Others are administered with a spinal tap – that’s where a long needle is placed into the spinal canal, where leukemia can lurk.

“The places it hides in all of us is in our spinal fluid,” Leavey said. “So we give chemotherapy directly into the spinal fluid, which means kids have spinal taps. And Jude had multiple spinal taps throughout the course of his treatment and multiple during that first month.”

That first month is crucial. And for the vast majority of kids with ALL, modern chemotherapy wipes away all signs of leukemia.

“Jude went through that first month of chemotherapy,” Leavey said. “But, unfortunately, he had leukemia at the end of that first month. Which meant his leukemia was declaring itself as being aggressive, as being hard to treat, as being high-risk, and as one that would require much more intensive treatment.”

Jude Cobler’s leukemia was aggressive and hard to treat, said Dr. Patrick Leavey with UT Southwestern and Children’s Medical Center in Dallas. Photo/Mark Birnbaum

VIDEO: An Unbreakable Bond

In this video, meet Jude Cobler and his family. “We really are brothers for a reason,” says Joshua Cobler, Jude’s brother. “This true love really does overcome all of the little things that you have to deal with.”

Video/Mark Birnbaum

‘This Place Isn’t So Bad’

During the next month, Children’s in Dallas became the Coblers’ second home. Jude’s maternal grandparents came from the Philippines to take care of older brother Joshua. Jude’s mom and dad slept and worked from the hospital.

Jude and Joshua Cobler during one of their hospital visits. Photo/Courtesy Cobler family

Even though Jude’s shiny brown hair fell out and he was often nauseous, his humor didn’t flicker.

His mom, Boots, kept a journal.

“A few months back, he asked me why he had to say in the hospital for so long,” she wrote. “I told him that’s because his chemo did not work. So he looked at me with a confused look and said, ‘Well, that’s dumb; you need to ask for a refund!’”

Like most kids, Jude didn’t like being poked and prodded, taking pills and feeling exhausted.

He did find solace in one place: the game room at Children’s.

“I would go there every morning, right when I woke up,” Jude said. “I’d be standing there, in front of the door, waiting for my other friends to come and play Super Mario Brothers.”

The kids looked different. They walked around with IV poles and wore face masks. But they looked happy, Jude said.

“They were having fun with each other and that’s when I thought, ‘maybe this place isn’t so bad.’”

Jude Cobler with his dad, Keith. Photo/Mark Birnbaum

Long-Term Challenges

Source: Cancer.org

Just as hospitals have evolved to be kid-friendly, chemotherapy has advanced to cure most pediatric cancers. Today, nine out of 10 kids survive ALL.

But Leavey says curing cancer in childhood often means serious problems down the line. Not just from missing school – Jude missed all of kindergarten – but also from the powerful drugs.

“It’s still being … clarified what the learning effect of cancer treatment is in kids,” Leavey says. “But if you’re giving sometimes weekly and then sometimes monthly … spinal taps and putting chemotherapy into the spinal fluid that bathes the brain, it’s not surprising, perhaps, there’s going to be some effect on learning.”

Young kids are more likely to have long-term learning challenges, everything from attention deficit disorder to reading and math troubles.

Chemotherapy and radiation can also damage organs like the heart and kidney, and sometimes lead to secondary cancers. That’s what happened to 58-year old Cyndi Sekerke of Mansfield.

Jude Cobler during one of his many visits to Children’s Medical Center. Photo/Courtesy Cobler family

She had Hodgkin’s lymphoma as a teen.

“The radiation that I received I’ve been told now was way too much for a human body,” Sekerke said. “I remember the radiation was so strong that under my arms, the skin literally turned black. It looked like charred meat.”

Sekerke recovered. She was cancer-free until she was 49, when breast cancer showed up.

“When you get it the second time around, and so much time has elapsed in between, I think my take was, ‘I’ve beaten this before. I’ve got this one. I can take care of this one.”

And she did with the help of chemotherapy. Sekerke also had a damaged heart valve replaced, which isn’t unusual decades after radiation.

Optimism Fades Away

In Dallas, Jude’s doctors would soon have to use radiation.

Jude Cobler with his mother, Boots. Photo/Courtesy Cobler family

Chemotherapy wasn’t working.

For the Coblers, optimism was beginning to slip away.

After the second round of chemo, Jude’s leukemia came back with a vengeance. His cancer cell count increased more than tenfold.

“I ran in the hallway in the hospital after that and I think everyone heard me crying,” said Jude’s mother, Boots. “That was when I started losing my faith a little bit. This is all I prayed about. I don’t pray for wealth. … I always pray for my kids’, my family’s, health.”

There would be an answer to Boots’ prayer.

And it was back at their Plano home — in the bedroom next to Jude’s.

COMING UP

For all the breakthroughs in cancer care over the last few decades, sometimes the best treatment just doesn’t work. Finding the right match would be tough. Read Chapter 2 of Growing Up After Cancer.