Jude and Joshua Cobler. Photo/Courtesy Cobler family

Jude and Joshua Cobler. Photo/Courtesy Cobler family

A Desperate Search For A Bone Marrow Match

For all the breakthroughs in cancer care over the last few decades, sometimes the best treatment just doesn’t work. That’s what happened to Jude Cobler of Plano. He was just 6 years old — and he needed a bone marrow transplant. Finding the right match would be tough.

Jude Cobler, left, needed a bone marrow transplant. The procedure is tricky – and dangerous. The Cobler family hoped that Jude’s brother, Joshua, would be a match. Photo/Mark Birnbaum

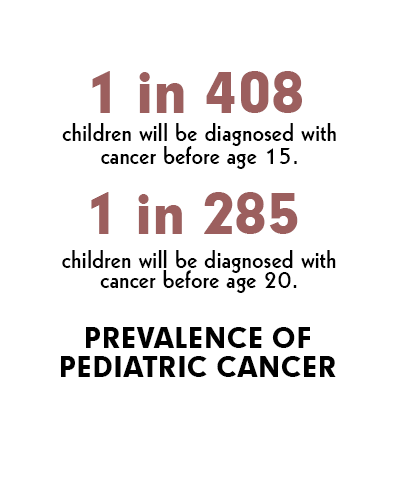

With cancer, there are a lot of odds.

Odds of chemotherapy working. Odds of complications. Odds of a full recovery.

Jude and his father, Keith Cobler. Photo/Courtesy Cobler family

When Jude Cobler’s chemo didn’t work, his odds of survival dropped drastically.

“They told us it’s now more like a 20 percent survival rate as opposed to the 80 percent,” said Jude’s dad, Keith. “We didn’t feel very good about that.”

Jude was diagnosed with Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia. Each year, about 2,500 kids are diagnosed with this type of leukemia.

Jude, who had turned 6, would need a bone marrow transplant.

The procedure is tricky – and dangerous. But before preparation can begin, you have to find the right bone marrow donor.

Keith Cobler is white. His wife, Boots, is from the Philippines. Being a mixed-race couple posed a challenge.

“Trying to find a match would be very difficult,” he said.

A potential match

How difficult?

Jude and Joshua Cobler. Photo/Courtesy Cobler family

There are around 16 million volunteer donors on the national Be The Match Registry. Of those, just 3 percent identify as mixed race.

Athena Asklipiadis is the founder of Mixed Marrow, a nonprofit that works to recruit donors. She’s part Japanese, Italian, and Egyptian and Greek.

“When it comes to minorities, about 7 percent are African-American, American-Indian 1 percent, Asian 7 percent,” Asklipiadis said. “The issue with multiple-race people is we are the fastest growing demographic. We are going to run into a lot more patients of mixed race that are going to have a need for a match that just isn’t there.”

For someone like Jude, it almost sounds like a lost cause.

The patron saint of lost causes just happens to be St. Jude. The Coblers, whose Catholic faith runs deep, named their second son after him.

There was one hope, though — Jude’s only brother, Joshua.

Boots Cobler kept a journal while her son, Jude, had cancer. Photo/Mark Birnbaum

Odds are one in four that a sibling will be a match.

After a blood test, the boys’ mom, Boots, got the news.

“I was like ‘Ahhhh!,’ yelling,” she recalls.

“I was overjoyed,” Joshua said. He was 12 at the time. “I wanted to be able to help my brother somehow, but I didn’t know how. The bone marrow transplant for me was an opportunity for me to do something for him that would be long-lasting.”

Video: About The Bone Marrow Transplant

“When we start out treating cancer in kids, the goal is cure,” says Jude Cobler’s doctor, Dr. Patrick Leavey, who’s with UT Southwestern Medical Center. “It … was our goal when Jude was diagnosed with his leukemia to cure him.” In this video, learn about the bone marrow transplant that saved Jude’s life.

Video/Mark Birnbaum

Turning The Body Into A Blank Slate

But finding a donor is just the first step.

Source: Cancer.org

Next, doctors had to take Jude as close to death as possible.

For Jude’s system to accept the foreign bone marrow, his body needed to essentially be a blank slate.

Jude’s doctor, Patrick Leavey, says preparation involves full body radiation and mega doses of chemotherapy drugs.

“Doses beyond which unless you were to receive a bone marrow as a rescue, you would not survive,” Leavey says.

Jude began with radiation. Twice a day for four days, he was strapped to a bed that turned like a rotisserie to treat all sides of his body. And then he was given a batch of drugs so toxic his parents couldn’t touch him without gloves.

Boots reads a journal entry from that time.

“December 19, 2010. … We have been wearing gloves when we have to touch him to avoid any skin burning,” she wrote. “This morning I accidentally touched the wash cloth he used, and I felt a burning sensation on my hand. So far, he is doing great. He didn’t even complain at 3 this morning when he had to take a shower. He is required to shower every 6 hours (9 am, 3 pm, 9 pm, 3 am). … Each time he showers, we need to change the sheets as well. So there’s a lot of work involved.”

Eventually, Jude was sent into a special bone marrow transplant unit, a place with strict isolation and specially-filtered rooms. Leavey says at this time, a patient is especially susceptible to getting sick.

“Having destroyed the body’s immune system, now we can replace that with a new healthy bone marrow,” Leavey said.

The Cobler family prays before a recent meal at their home in Plano. Photo/Mark Birnbaum

‘A Greatness To It’

Two days before Christmas 2010, Joshua checked into Children’s Medical Center. He was whisked away on a gurney to donate his bone marrow.

Jude Cobler, right, with his brother. Photo/Courtesy Cobler family

“It was very odd knowing that we had one child upstairs that was very sick and here was his possible savior at that point downstairs ready to go through the transplant,” Keith Cobler said. “It was a very emotional time. There was a greatness to it, too.”

After a doctor drew out the bone marrow from two small incisions over Joshua’s hip bone, the bright red liquid was placed into a bag and fed into Jude through an IV. Joshua says it was painful, but not too bad.

“The day that it happened, when I woke up from the procedure, I remember that he was falling asleep,” Joshua recalls. “The only words he said to me before he fell asleep were ‘I love you.’ And we both fell asleep in the same room.”

But the odyssey wasn’t over.

Jude had survived aggressive chemotherapy and radiation. He had even beaten the odds and found a bone marrow match.

Next, he’d have to face the complications of cancer, which would alter his body — and his relationship with his brother.

COMING UP

Jude’s bone marrow transplant changed him physically. It changed him emotionally, too, by creating an unbreakable bond with his brother. Read Chapter 3 of Growing Up After Cancer.

Cancer’s Toll On A Kid

Cancer can take a toll on a kid’s physical health, but there are psychological effects, too. Many survivors experience anxiety, while some suffer from post-traumatic stress.

Dr. Shannon Poppito is a psycho-oncologist who works with patients who’ve recovered from cancer at Baylor’s Sammons Cancer Center. Poppito says children often experience cancer differently than adults and teens.

‘There’s this hypervigilance’

Dr. Shannon Poppito Photo/Courtesy Baylor Scott & White

“Four- and 5-year-olds are not going to take up cancer the same way as a 7, 8, 9, 10-year-old,” Poppito said. “Because the developmental shifts that are occurring in their bodies, in their brains, are shifting. These little kiddos, they’re just exploring the world for the first time. They’ll understand cancer as not feeling very well and not being happy that they can’t go out to play. … But they look to their parents – if they’re angry, if they’re sad, if they’re nervous. They take on whatever the parents are experiencing of their cancer.”

“There is something about having cancer that is ever present in your mind, that once you’ve overcome the cancer, you want to make sure you are doing everything in your power,” Poppito said. “So there’s this hypervigilance, this control to make sure that you’re doing everything to take care of yourself. Parents should just be aware of if the fears of contamination start affecting a child’s functioning. Preemptively, perhaps, have a child go see a psychologist … because, as a psycho-oncologist, I see patients that struggled with cancer at 5 years old that will come to me in their 20s having not worked through these fears of contamination and now it has become debilitating, and now they struggle with obsessive-compulsive disorder or they struggle with issues that were left unattended.”

Teenagers and cancer

“Teenagers will experience cancer, maybe some similarities to an 8 or 10-year-old, but different in the fact that stress will trigger a stress hormone called cortisol,” Poppito says. “Cortisol then, working together with estrogen, which females are having course through their bodies as a teenager, will spike this traumatic stress even more. On top of that, we have identity issues. So she’s trying to find her own sense of identity in the world. All of these bio-psycho-social underpinnings will impact how cancer develops this post-traumatic stress in the body, the mind and the spirit of a teenager.”

‘A sense of resiliency’

“What I want to underscore is not only the post-traumatic stress, but also the post-traumatic growth that occurs in patients who have cancer, especially in teen years. They’ve learned a sense of resiliency, a sense of overcoming, their sense of identity becomes stronger. … I don’t think we have enough literature out there on post-traumatic growth — that you can learn something from the cancer you can learn how to make it meaningful and purposeful.”

Listen To The Conversation With Dr. Poppito