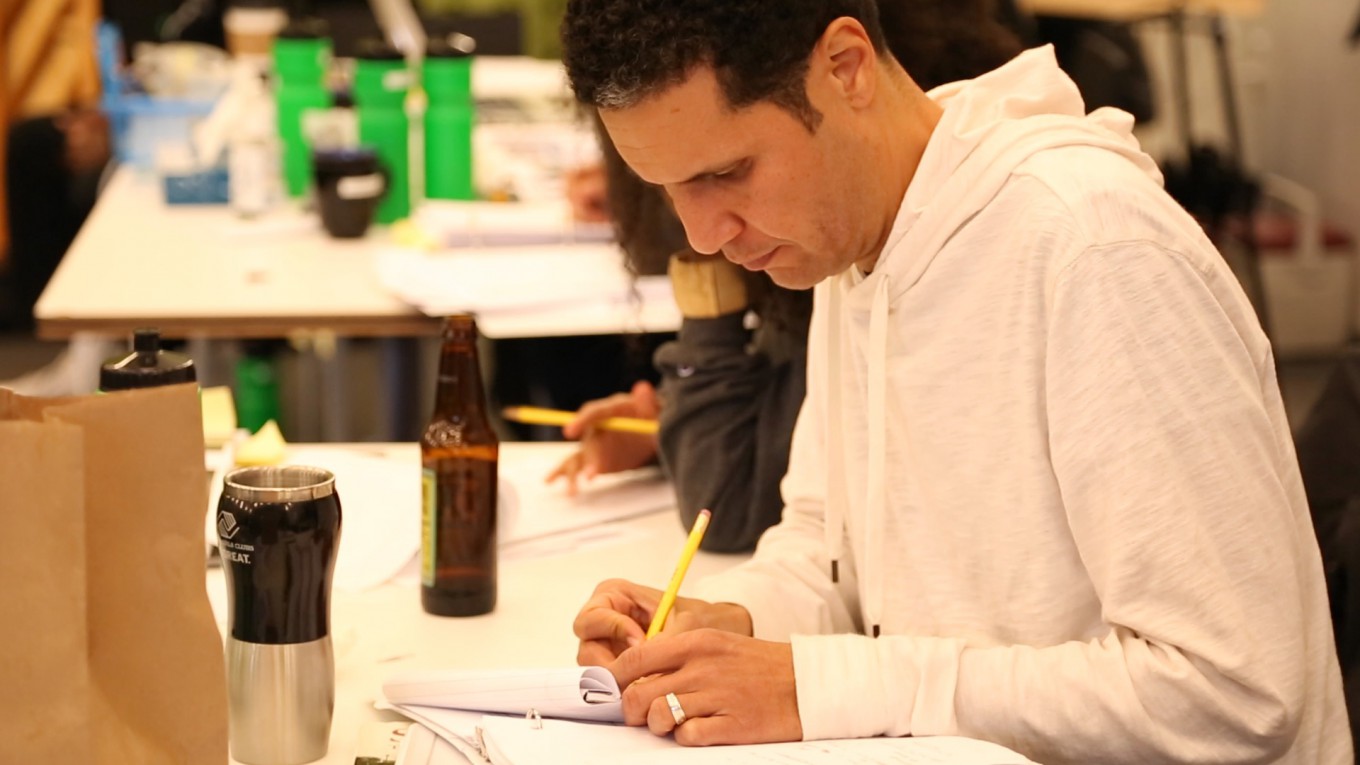

Playwright-in-residence Will Power writes notes during a rehearsal of "Stagger Lee".

Playwright-in-residence Will Power writes notes during a rehearsal of "Stagger Lee".

The Creator: Will Power

As a kid, Will Power had a personal interest in the legend of Stagger Lee. Forty-two years ago, he was born William Wylie, but his mother said his own middle name almost was Staggerlee.

“She always told me that they didn’t know how to spell the name,” he recalls, “and that was the reason that wasn’t my middle name – because it comes from the oral tradition. So is it Stag-o-lee? Is it Stackolee?”

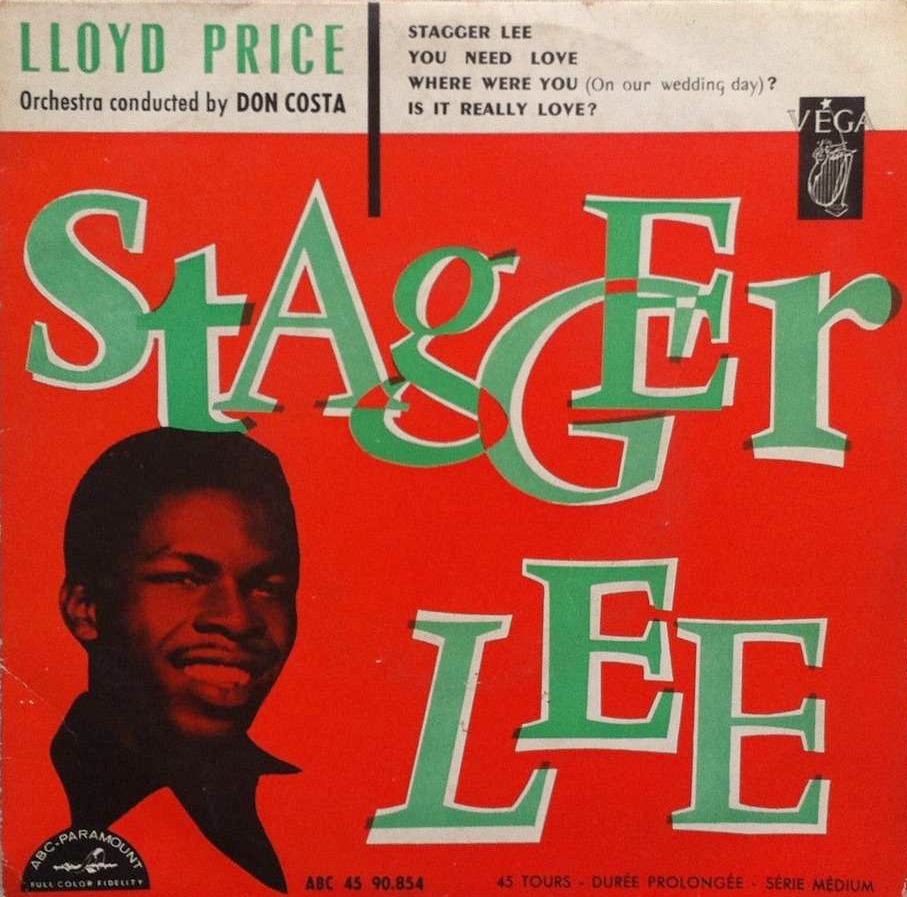

Lloyd Price’s 1959 hit album

To Power, Stagger Lee was the prototypical rebel, a hard guy who didn’t take any guff. If you’re younger than 40, odds are, you’ve never heard the name. Older than 40, you may remember Stagger Lee from Lloyd Price’s 1959 song (“Stagger Lee went home / And he got his .44 / Said, I’m goin’ to the barroom / Just to pay that debt I owe / Go Stagger Lee!”).

That #1 hit single was only one of a dozen versions — by the Grateful Dead, Wilson Pickett, Woody Guthrie, even James Brown (watch and listen to some of them here). All of them were spawned from the same historical event. In St. Louis in 1895, a black Texas gambler named Lee Shelton shot another man named Billy Lyons. No one knows for certain who wrote the original song, but in some versions, “Stagolee” is a cold-hearted killer who’s sent to hell. In others, he’s a heroic outlaw, defying the authorities. Either way, Stagger Lee became an African-American folk figure.

It’s this figure who lives again in the show, Stagger Lee, a rare, ambitious, new musical for the Dallas Theater Center because it was created entirely here from scratch. (Many other “premieres” have been developed elsewhere and brought to the DTC to test the work — with the story, music and artistic team already set.) It was the idea of Will Power, the company’s artist-in-residence, to devise a show about 20th-century African-American life. He’d use Stagger Lee as one of several mythic figures who’d be ordinary people quarreling and struggling and seeking better opportunities for themselves over the years. For these African-Americans, Stagger Lee would be both a bully and a blessing, a threat and a source of strength.

Power, poetry and picket signs

When he was growing up in San Francisco, Power’s parents were political activists. His father, for instance, was with the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee or SNCC, one of the groups at the forefront of the civil rights movement in the ’60s and early ’70s.

“Like that was my world,” Powers recalls, “Afros and picket signs and also the underside of that, the drug use, the idealism and the pain, all that stuff was there.”

Will Power, Dallas Theater Center artist-in-residence, and writer of ‘Stagger Lee’

Sandra Jackson-Dumont, the chair of the education department at New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art, grew up with Power in the Fillmore district, San Francisco’s historically black neighborhood, home of the Black Panthers. They attended the same high school and the same community cultural center — where they were exposed to creative, Afro-centric theater and music, taught by Judith Holton, a former dancer and vocalist with Sun Ra, the space-age jazz orchestra leader.

“When we were in high school,” Jackson-Dumont recalls of Power, “I remember thinking, ‘God he’s so smart.’ He was just really well read, very sure of himself. And hip-hop was always a part of his thinking and reading but I think it also came to him through the lens of theater and performance.”

In fact, by 14, Power was already an MC in hip-hop shows in the Bay Area — Will Power became his stage name. By the ‘90s, he was part of the group, Midnight Voices. After moving to New York, he attended the Tisch School of the Arts at New York University — and became a pioneer using hip-hop in theater performance. Tall and lanky, Power created characters through chanted vocals and vivid accents. More than the conventional boasts of rappers, he told stories — made the stories feel alive with his expressive face and rubbery, b-ball moves (see his TEDxSMU performance here).

In New York, he rapped on HBO’s Def Poetry Jam, but it was his success in 2006 in developing a hip-hop, off-Broadway version of the Greek tragedy, Seven Against Thebes, that got Power on The Colbert Report and interviewed by Bill Moyers on PBS (below).

A creative opportunity

In 2010, Power won SMU’s Meadows Prize. The $25,000 award requires the winner to visit Dallas to develop a local project. Power brought along his ideas about the myth of Stagger Lee. With The Seven, his version of Aeschylus’ drama, Power flipped ancient myths into street characters and contemporary DJs. His new project would do something similar to Stagger Lee and other black archetypes like the lovers, Frankie and Johnny — the ones from the classic ballad about a man shot by his woman ’cause he done her wrong.’

Think of it, Power says, as if it’s his response to Stephen Sondheim’s Into the Woods: He’d take old folk tales, re-combine them and extend them forward — to see what happens.

Justin Ellington, co-composer of ‘Stagger Lee’

“Will really is into what shapes a community, and these myths do that,” says Justin Ellington, composer, music director and Power’s longtime collaborator. “And it’s a simple story – a family looking for a better opportunity. The family just happens to consist of these mythical figures.”

Fittingly, Power has moved his own family to Dallas for this creative opportunity. Musicals may be popular but they’re also pricey to develop and stage. Developing Stagger Lee has required years of piecing together not just stories and artists, but money. There was the Meadows Prize and two years later, a $50,000 grant from the Donna Wilhelm Family New Works Fund. Then came money from the Andrew Mellon Foundation to fund the playwright-in-residence position at the DTC, plus a $70,000 grant from the NEA for the Stagger Lee production itself.

As a result, Power is in a rare position: He’s both playwright-in-residence at the Theater Center and a faculty member at SMU. He wants to bridge the two institutions that often haven’t worked well together.

Power thinks SMU has an exceptional theater department, but he wants to work on getting students to build ensembles on their own, to develop their own stories. “How do you take a group of seven-eight artists,” he asks, “and create a theater piece where you develop it from the ground up?”

Building a show from the ground up is, of course, precisely what he’s been doing on a vastly larger scale with Stagger Lee. It’s the largest — the longest, the most complex — theater piece he’s ever tried.

“The blessing of this whole process,” Power says, “it’s we’ve had like four or five workshops over these last few years. And we had just in October-November about a five-week workshop. That never happens in America, you know? So we had, like, a five-week rehearsal, where I was really able to figure out some critical moments. Then I had a month off to do another draft, and now we’re back into it.

“Again, you never know. Hopefully, we won’t get into previews and we’re like, ‘Ohmigod! The second act doesn’t work!?”