Image provided by Dallas Theater Center.

Image provided by Dallas Theater Center.

The Music: Justin Ellington

Justin Ellington sits at the piano in the rehearsal room at the Wyly Theatre, running through a wistful, mellow, little tune. He’s explaining why he didn’t want the Dallas Theater Center‘s new show, Stagger Lee, to stay in just one musical time and place: St. Louis, 1910. It’s a place Ellington calls ‘ragtime land.’

Co-composer Justin Ellington. Photos: Jerome Weeks

“In ‘ragtime land,'” he says, “you’d hear a lot of – ” and he pumps out a few bars of a Scott Joplin rag, four-on-the-floor, all upbeat and solid. “There’s a type of hope in the chords. But I don’t hear sadness in that.”

And Stagger Lee was going to need some sadness — and some conflict. The show was originally set in St. Louis because the classic song, “Staggerlee” — the one that inspired the show — was set there. That’s also where the 1895 shooting happened, the one that started the legend of ‘that bad man, that mean ol’ Stag-o-lee.’

But as the musical was worked on the past several years at the Theater Center, its scope expanded considerably. Will Power, the author of Stagger Lee, wanted to tell a story of young black couples in the early 1900s as they try to move from the country to the city, escape Jim Crow racism, build new homes. Justin Ellington is Power’s longtime collaborator, a composer and music director who’s worked with the former hip-hop artist on six shows now. Ellington’s also worked for Shondrae Crawford, better known as Bangladesh, who’s produced tracks for Beyoncé, Eminem and Ludacris.

And as the co-composer of Stagger Lee, Ellington had a suggestion for Power: “You know what would really be cool for not only the story,” he recalls with a chuckle, “but the music and all designers involved, is if we just kinda move throughout different time periods?”

Frankly, he admitted to Power, his suggestion was a bit selfish: “I would just love to explore all these different forms of music.” But, he argued, it would also make for a rich musical and theatrical canvas. All the fashions from the different eras, all the dances from the cakewalk to the jitterbug. And all that history. Besides, Power’s own storyline drew not just on the legend of “Staggerlee” but on other folk characters as well, like the violent lovers from the song, “Frankie and Johnny.”

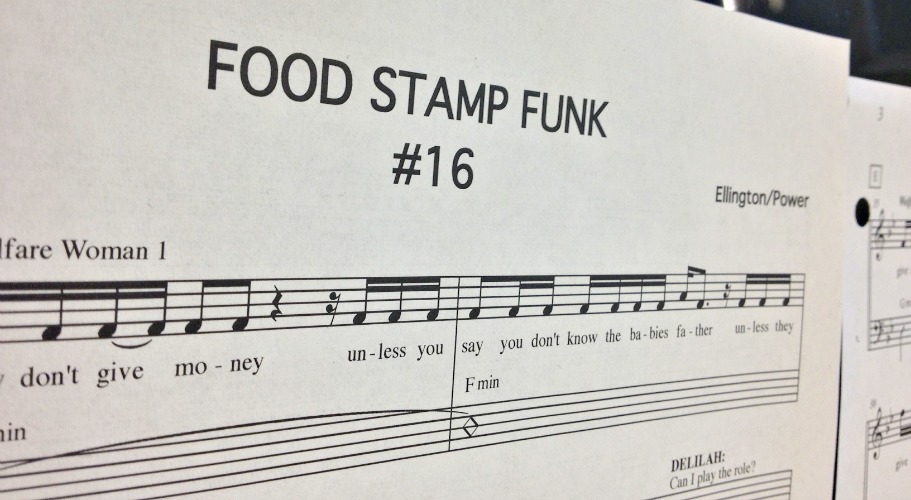

The title page of a score from “Stagger Lee”‘s second-act.

So now Stagger Lee jumps from St. Louis to Harlem to Chicago and beyond. It’s become the saga of the civil rights struggle and the Great Migration, the mass exodus of African-Americans from the Deep South into the big cities. But that also means Stagger Lee is an epic history of 20th century black music. It starts with spirituals from 1890s Mississippi then works its way through jazz, doo-wop, all the way to 1987-era techno-funk from Detroit.

Okaayyyyy. So that’s a lot of musical-historical turf to cover. But Ellington says he can just hint at this or that style as the show goes along. He doesn’t have to document every musical development or historical by-way. Like, he says, when the show segues from 1930s jazz to 1940s swing. Ellington promptly lays down a thumping bass rhythm — “this kinda Cab Calloway vibe,” he calls it, referring to the ‘hi-de-hi-de-ho’ bandleader and singer — then his chords shift into something richer, grander. They’re chords, he says, that evoke the early days of swing. And they’ll come up — but just in passing, a quick citation, a brief echo.

Speaking of swing, given the Ellington family name, the question is inevitable: Is Justin related to Duke Ellington? Online searches do indeed bring up references to ‘nephew’ and ‘grandson.’ But he’s really only distantly related, Justin insists, and only through Duke Ellington’s wife, Edna.

Whatever the family DNA, Justin Ellington is a musical-historical chameleon, drawing on all these styles and making them — as catchy or evocative as they are — making them serve the story in Stagger Lee. In fact, Ellington sees that story – the story of black people pushing for a better life – as actually embedded in his music, in its component parts.

Justin Ellington in rehearsal at the Wyly Theatre.

”The whole show is the blues to me,” Ellington declares. “And that is, what the world should be –” he plays a lilting, rising passage. “And what the world is.” His music goes into a contrasting, descending, blues progression, a series of chords intimating there’s only worse to come.

But, he adds, “those things work together, you know?” And now his lilting theme meshes with the bass line. We still get the flatted ‘blue notes’ — all these rubs and nasty bits, as he says. “But there’s still hope. And I think to really get to the hope, you have to address the blues.

“And I think the show is that.”