Students participate in a sack race during Field Day at Wimbish Elementary on May 18, 2018. Photo: Lara Solt

Students participate in a sack race during Field Day at Wimbish Elementary on May 18, 2018. Photo: Lara Solt

Under Pressure To Improve, Arlington School Starts With ‘Good Things’

The race to save failing schools doesn’t just happen in inner cities. Suburbs like Arlington face the same challenges. Two miles west of the Dallas Cowboys’ glitzy AT&T Stadium, Wimbish Elementary is trying to turn itself around. It’s been on the state’s “Improvement Required” list for four straight years. If it doesn’t succeed by next year, the state could shut it down or take over the district.

Principal Kari Pride greets her students every morning. As she stands outside Wimbish Elementary, she shakes every kid’s hand.

Students, like 13-year-old Israel Henry, also help out. He’s one of the older students at the school, which goes up to the sixth grade. Israel holds the front door open for his classmates as they walk in.

“Hello, good morning, Vince Brother. Hello, good morning, Nathan. Hello, good morning, Samaya.”

Israel takes his job seriously.

“Sometimes it can get frustrating because I can’t stop from having a smile on my face,” he said. “Although some students when I do it, they just don’t say nothing.”

Morning greetings and handshakes may seem like no big deal. But, Pride said, this is part of a larger strategy to jump-start learning. It may also be the only positive touch some of these kids experience.

The school implemented the initiative — called Capturing Kids’ Hearts — two years ago. Wimbish though has been around for more than half a century.

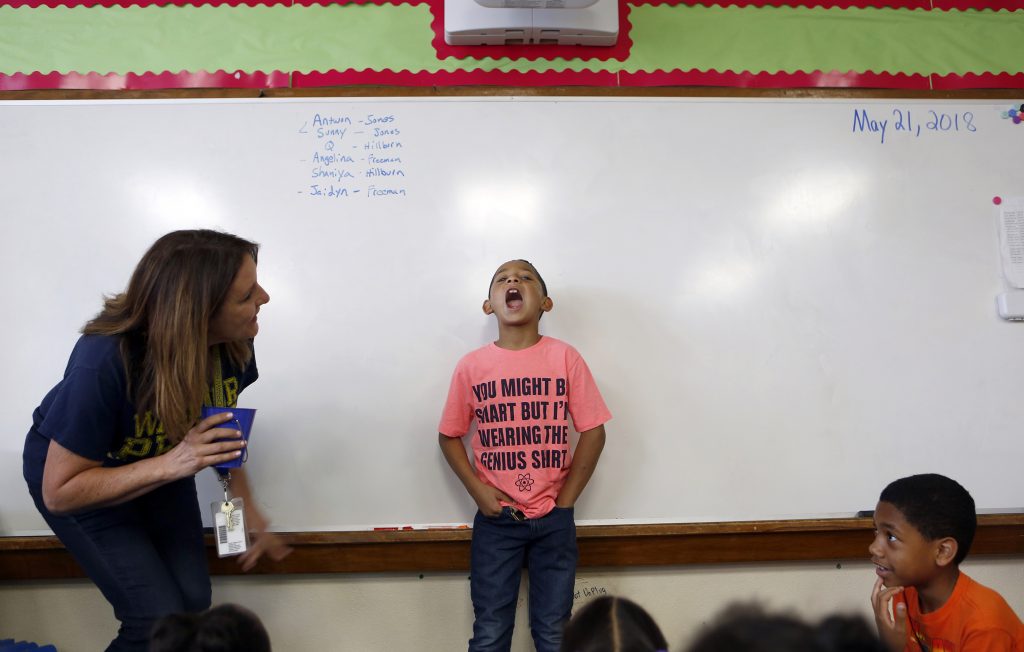

Kindergartner Arabella Morales raises her hand to talk about “Good Things,” a tradition where the students talk get to share something good that happened to them, at Wimbish on May 21, 2018. Photo: Lara Solt

The students here face many challenges. Eighty-four percent are economically disadvantaged, which is a higher rate than the district or the state.

And then there’s what’s known as the mobility rate. At Wimbish, it was 34 percent during the 2015-16 school year. That means more than a third of kids weren’t there for six weeks or more that year.

The principal says these outside factors affect kids’ ability to learn.

“If you’re in a fight-or-flight mode, it’s hard to have your brain where you can learn,” Pride said. “Sometimes it may seem like they can’t learn, and it’s not really that they can’t, it’s just that they’re so stressed out about other things, it’s hard for them to be present.”

The school exceeded the state’s passing standard with rating of “Recognized” for the 2009-2010 school year. And it “Met Standard” during the 2012-2013 school year. But for the last four years, Wimbish has received the state’s worst rating: “Improvement Required.” For more on the state’s accountability system, read the series introduction.

That’s why this turnaround plan is so important. One key element: Get the kids to focus on the good things in their lives. Teachers ask students to share these “good things” — losing a tooth or going out to eat for a cousin’s birthday — at the beginning of class.

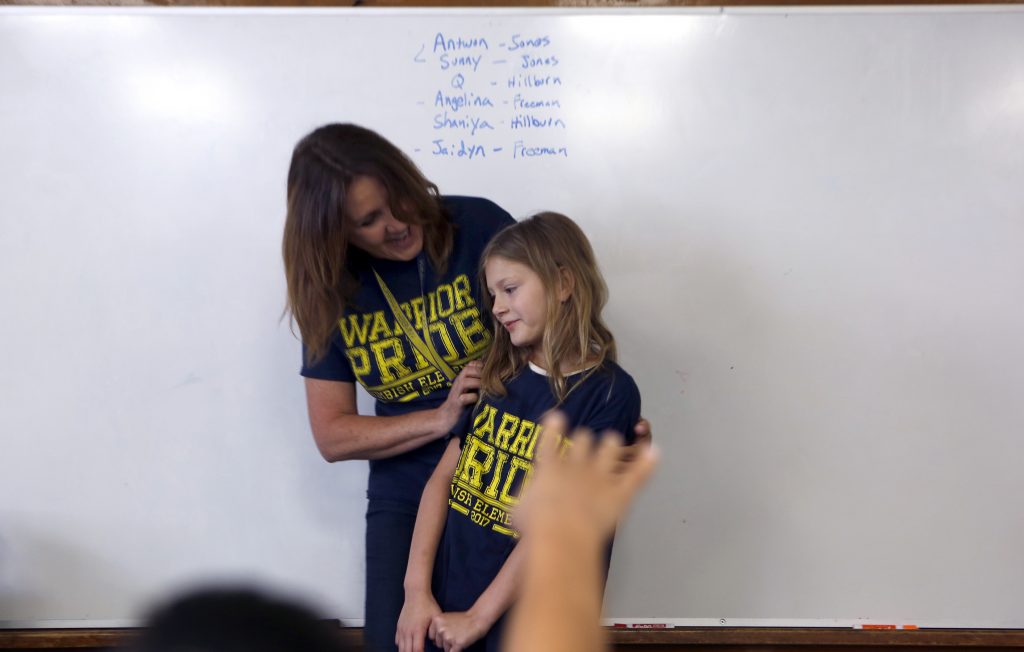

Brenda Donoghue, who teaches second grade, is in her first year at Wimbish.

“I love the challenge of it. I just felt, ‘If you let me, by the end of the year, I’ll get them where they need to be,’” she said. “But the first thing they had to have was that love. And that, they had to know that they knew they could trust me.”

Donoghue said her main goal was to get her students to “feel the high of working hard.”

“There’s no feeling of failure in there. There’s no feeling of being afraid to give an answer,” she said. “They are praised for trying to answer and a lot of their frustration will come when they have to really use their brain and think because they want it easy or they’re the smarter ones…and that’s not what we’re doing.”

She said working in small groups of four to five students helps. This way, Donoghue can see who’s struggling in certain areas and focus on helping that student.

Digging into data has become the mantra of education reform. Wimbish is taking it to a new level by teaching kids how to track and understand their own data.

Debra Wall, the school’s dean of instruction, said students set goals and keep track of how they perform on tests.

“One class, they gave them a choice. Do you like bar graphs or do you like line graphs? What do you want? The kids love the line graphs, so they did line graphs,” Wall said. “Then one class actually started building loops so for every assessment they passed, they got to put a loop up and the loops are hanging up all over the classroom.”

Jovanni Coronado, 8, pulls out the folder with a bar chart he colored himself.

“Every month, we do Istation tests,” he said. “Every month, if we go higher, we get to get a new level. At the beginning of the year, I was at 214 and now I’m at 250.”

For years, test scores at Wimbish have ranked among the lowest in the district. Last school year, 72 percent of fifth-graders passed the math assessment; 62 percent passed reading. To compare, the passing rates for fifth-graders across the Arlington school district were 82 percent in math and 76 percent in reading. Explore more data on Wimbish.

Principal Pride said there are some early signs of a turnaround; preliminary fifth-grade test results show a surge in passing rates.

“We are at 19 and 20 on reading and math in the district of 56 schools,” said Pride. “So we’ve gone from the bottom to being in the top half. It is very significant.”

Late last week, the Texas Education Agency said there were glitches with this year’s standardized test and that those test scores would not be used against schools like Wimbish.

While Pride said it can’t happen overnight, the pressure is on to get off the state’s list of failing schools.