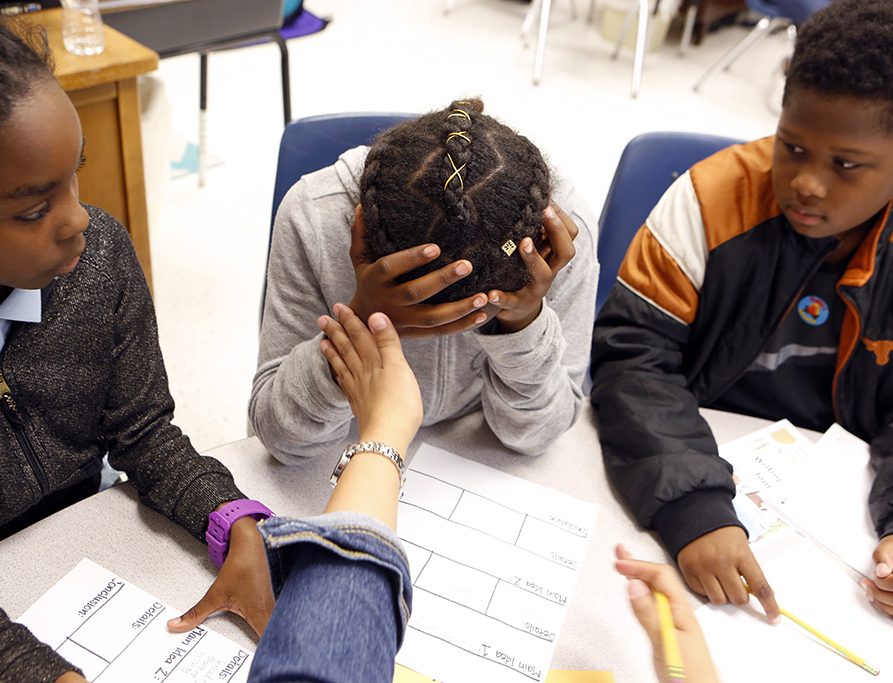

Marjorie Garay works with fourth-graders (from left) Katanga Minimums, Andre Gill and Lance Moss on April 3, 2018. Photo: Lara Solt

Marjorie Garay works with fourth-graders (from left) Katanga Minimums, Andre Gill and Lance Moss on April 3, 2018. Photo: Lara Solt

Struggling Fort Worth School Reboots As An ‘Academy’

Mitchell Boulevard Elementary is one of five low-performing schools in the Fort Worth Independent School District that has been designated a “leadership academy.” The school struggles with kids regularly moving in and out and low literacy rates, but administrators believe changes made this year — including an ambitious literacy goal set by the district — will put Mitchell Boulevard back on track. The state has rated the school “Improvement Required” for three consecutive years.

It’s 5 p.m. at the Leadership Academy at Mitchell Boulevard Elementary, but these 5- to 10-year-old kids haven’t gone home. They’re getting ready for dinner. About this time every day, a vendor delivers meals such as spaghetti, turkey and cheese wraps or chicken nuggets. They include a side of veggies and sometimes fruit.

Serving breakfast, lunch and dinner is just one change Mitchell Boulevard has made this school year as a leadership academy. School days are longer. There’s something called an intervention block from 3 to 4 p.m. that includes targeted and small group instruction. And there’s an after-school program from 4 to 6 p.m. Hanging around after school isn’t mandatory, but about 100 kids — one out of every four here — stay late.

“My momma, she just signed me up because I wanted to learn more,” said 9-year-old Makayla Davis. Like many of her classmates, Makayla needs help.

“I need to be reading a lot. Reading, it feels like it’s boring, but it’s not because I tried it,” she said.

The adults at Mitchell Boulevard want more kids to feel that way. Reading has to appeal to kids to make a dent in test scores. Principal Aileen Martina-Quiñones, who’s in her first year at Mitchell Boulevard, says it’s critical.

“Our fourth-grade students last year were — at least half — two, three grades below,” she said.

The school has a history of kids struggling with reading. In the last decade, passing rates among fifth-graders for reading have dropped 10 percentage points. Last year, just three out of every five fifth-graders passed. It’s not just a problem at Mitchell Boulevard. Across the district, only three in 10 third-graders are reading on grade level. Students who aren’t reading on grade level are four times more likely to drop out.

That’s why Fort Worth has set an ambitious goal: Get 100 percent of third-graders reading on or above grade level by 2025. Educators are working toward the goal by making learning and test prep fun and teaching vocabulary and reading in all subjects, even physical education.

Marjorie Garay, a third- and fourth-grade teacher at Mitchell Boulevard, says getting ready for the all-important STAAR test was nothing like this last year.

“They did a lot of worksheets and a lot of just…kind of ‘teach the test.’ And I think this year, they’ve really gone outside the box and have been more creative,” she said.

“We interact more within the classes and not just ‘stay within your own classroom.’”

Students come and go every day

While administrators and teachers have control over what goes on in the classroom, one factor outside of school is hurting students. Families are moving in and out of Mitchell Boulevard on a daily basis. That’s contributing to the school’s high mobility rate.

According to the most recent data available, the mobility rate at Mitchell Boulevard in 2015-16 was nearly 33 percent, meaning nearly 130 kids weren’t there for six weeks or more out of that school year. To compare, the mobility rate across Texas in that same year was 16 percent. That makes it difficult for students to learn and retain information. And teachers are forced to bring students up to speed.

Principal Aileen Martina-Quiñones (right) meets speech therapist Jill Williams to discuss student performance on April 3, 2018. Photo: Lara Solt

The school serves many children in nearby apartments.

“We have the three apartments that we serve,” Principal Martina-Quiñones said. “Every day we enroll and we withdraw one or two students. It’s every day. So that’s a big challenge.”

Martina-Quiñones says some apartments have short-term leases, so some families may move to the complex offering the best deal, even if that’s in the middle of the school year.

“My goal is that at the end of the year, when the parents, when the community sees the progress the students have made, that they will want to stay,” she said. “I want to see their growth from now until they move on to secondary [school].”

Students and teachers in the hallway during Parent Night at Mitchell Boulevard Elementary School in Fort Worth, Texas on Thursday, March 8, 2018. (photo © Lara Solt)

Issues at home ‘on their shoulders’

Along with academic challenges, some kids at Mitchell Boulevard are dealing with problems at home. Teacher and coach Charles Burns says he sees it all.

“You have kids that basically they raising themselves. You have some that are waking up [and] taking care of siblings as a child themselves,” he said. “We have some that are being neglected, some that are being abused. They see abuse. And they have that all on their shoulders and they bring that to school with them every morning.”

All this tension came to a head in the fall. Fights broke out. Kids walked out of class. Something had to change. The school moved a couple of key staffers like the counselor from a portable outside to the main building. That made it easier for kids to stop by.

Another big change, the school created a “house system” — think “Harry Potter.” Instead of Gryffindor and Ravenclaw, students from third to fifth grades are assigned to a “house” that represents a different value like Honor, Courage, Knowledge and Trust.

“The house system has made a great shift in our culture,” said assistant principal Vanessa Cuarenta. “It has made a very positive incentive to follow the values.”

Teachers reward students who embody those values.

“The students are definitely really proud of their house when they wear their shirts on Fridays,” she said. “They’ll be able to tell you what their house stands for, and when they walk down the hallway, they’ll be like, ‘Oh you know, we’re part of the same house,’ and it also serves as a reminder [of those values].”

Connecting with parents

The school also has been working on developing better relationships with parents. Last fall, all of the leadership academies in the district participated in a “community walk.” Teachers and staff went door to door meeting families, bringing them water and sharing information about the schools.

“We think that with parental interaction, it shows growth in the kids’ academics,” said teacher Marjorie Garay, who also lead the walk. “Once there’s a relationship with the parents, we’re able to bring the kids more success.”

Monique Bowdy watches as her son, fourth-grader Lebron Bowdy, work on a tablet during Parent Night at Mitchell Boulevard on March 8, 2018. Photo: Lara Solt

During a family night at the school, Monique Bowdy was there with her 9-year-old son, Lebron, who’s in the fourth grade. She says one thing she’s noticed in her son is how much he mentions a certain someone.

“His teacher,” she said. “That’s all he talks about is his teacher.”

Asked what he likes about his teacher, Lebron said, “That she help me.”

What does she help him with?

“Uhhh math, reading and writing,” he said.

The big changes at Mitchell Boulevard seem to click with Lebron. And that, at least, is a small sign of hope for the adults trying to turn this struggling school around.

They have to. Otherwise, another year or two of a failing grade means closure or a state takeover.