The History

It’s the gala opening of the Meyerson Symphony Center, September 6, 1989. To get to the hall, invited guests find they must walk past protesters who chant against racism and elitism. When then-Mayor Annette Strauss steps out of a limo – she’d been a spearhead for the Meyerson at City Hall – the protesters display cupcakes and chant, “What does Annette say? Let them eat cake!” An image of the protesters wrapped in chains even runs in Time magazine.

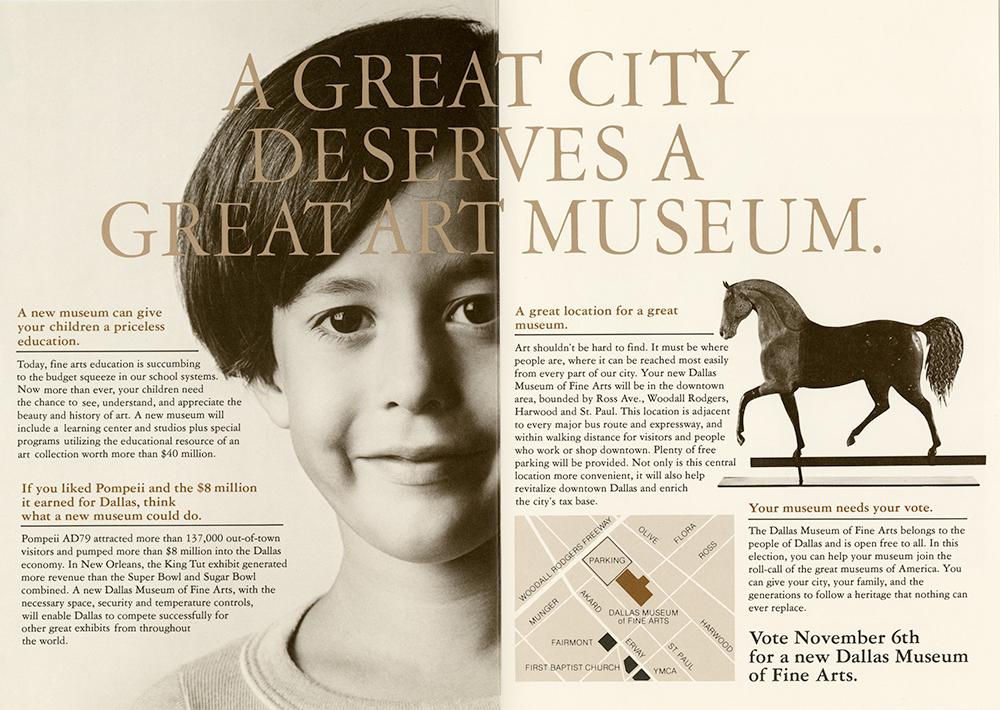

The plan to build the Dallas Symphony a new home, a better home than the Music Hall at Fair Park, started a decade before. It was a typically grand, ambitious, Dallas goal – to create a concert venue as great as Carnegie Hall, as great as the best halls in Europe (and, along the way, save the Dallas Symphony from near-bankruptcy). The plan won voter approval in two bond elections – which featured the campaign slogan, “A Great Concert Hall for a Great City.”

Of course, the campaign also featured the slogan, “A Great City Deserves a Great Art Museum.”

But by the time the hall opened in 1989, some Dallasites felt the Meyerson was a boondoggle. Or just a bauble for the wealthy.

What had changed?

For one thing, the racial makeup of Dallas politics. Domingo Garcia was one of the leaders of the opening-day protest. He says the concert hall came to symbolize what was wrong with how Dallas was run.

“When the Meyerson came up,” Garcia recalls, “at the time, Mexican-Americans, African-Americans were totally excluded from City Hall. Our tax dollars were going to finance entertainment for the wealthy. And we thought it was unfair. And we wanted to change the way the city is governed because we’re not at the table.”

Two years after the Meyerson opened, Federal District Judge Jerry Buchmeyer mandated single-member council districts for Dallas. He ruled the city’s at-large districts had historically, systematically, prevented minority groups from being elected to the council and wielding political power. Later that same year, Domingo Garcia was elected to the city council.

Economic Crisis

What also had changed during the ‘80s was the Texas economy. In 1985 – as fundraising for the Meyerson geared up – the price of a barrel of oil sank from $35 to $9. The year before, the savings and loan scandal began in Mesquite when the Empire Savings and Loan collapsed. Nearly half of all the S&Ls that failed in the United States failed in Texas. By 1987, Texas unemployment hit nine percent – a figure higher than during the Great Recession in 2008-11. By decade’s end, Dallas led the country in vacant office space.

Laurie Shulman is author of a history of the concert hall, The Meyerson Symphony Center: “I think the bad economy had a huge impact on the public’s willingness to pay for enhancements to the concert hall.”

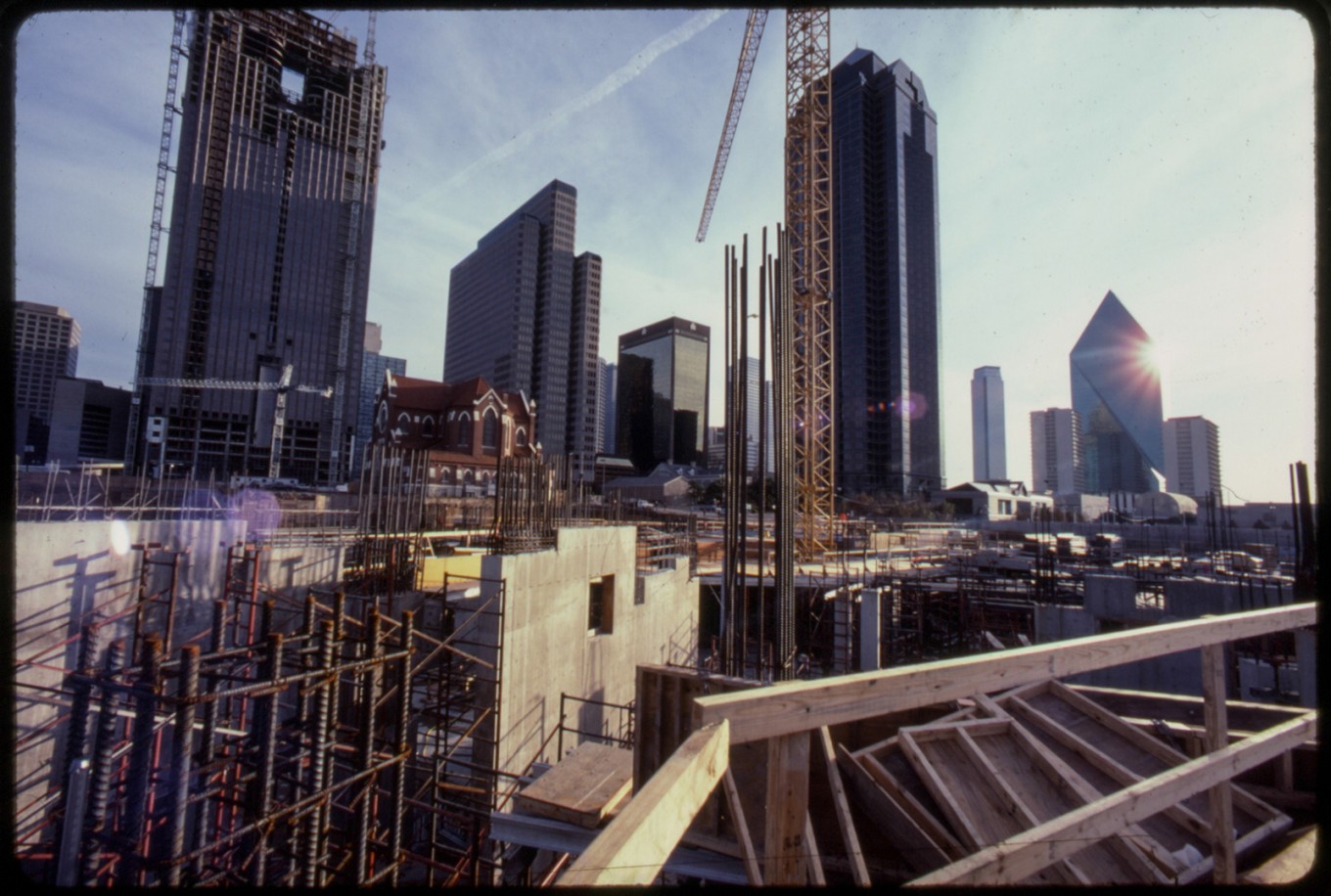

It wasn’t simply a matter of timing. The Meyerson was complicated – from its design to the land swaps that put it where it stands. Funding the hall was an innovation as well. In 1982, both the Dallas Museum of Art and the DSO won voter approval for city bonds to finance their new venues. When the DMA opened in 1984, it was the first arts facility developed through such a public-private partnership.

But the DMA didn’t generate the kind of opposition the Meyerson did when it was built. With the DMA, the public paid for less than half of the museum’s $52 million cost. The Meyerson was different. Its financing followed the plan laid out in 1977 by Boston consultants, Carr, Lynch: City tax money would cover 60 percent of the costs; the symphony raised the remaining 40 percent. Because the 1982 bond election included $28.6 million for the concert hall, that meant – with the 60/40 split – the hall’s budget would be capped around $48 million.

Model of Dallas with proposed arts district, 1979 | The Carr, Lynch Study – “A Comprehensive Arts Facilities Plan for Dallas” – boldly tied the arts to the redevelopment of downtown Dallas. It hammered out in detail the ambitious idea of an arts district and the public funding that would help leverage private money. An arts group wanting to build a venue in the district would need to raise 40 percent of its construction costs. The city would cover the remaining 60 percent. Plus, taxpayers would take on 75 percent of the land price. The new venue is then deeded to the city – which gains a public facility for far less than full price. But the city will also be on the hook for maintenance. Dallas owns it, Dallas must keep it up, Dallas is the landlord. The policy is adopted by the Dallas City Council in December 1979.

“It had two sources of income – city and the symphony – but nobody controlling the cost,” George Schrader recalls. He was Dallas city manager in the 1970s, and in 1981, he became the DSO’s point man on construction.

![Budgeting And Bargaining | After he was appointed the administrative construction manager for the DSO, serving as liaison with the city, George Schrader says he went to Dallas' public works department with concerns about the concert hall's budget. "And they said, 'Oh my yes, way over the budget, let's just go ahead ... toss the bids out and start over again. We can't understand why the symphony continues to pursue a symphony hall of this cost.' I went to the symphony, and they said, Leonard Stone [executive director of the Dallas Symphony Association] said, 'Oh my yes, we don’t know why the city didn’t control costs long ago.'" Schrader learned what the symphony knew - that the $28.6 million was a figure chosen by city officials (ultimately with the symphony's agreement) because it could get approved by Dallas voters. It had little relationship to what was being planned or what was needed.](http://stories.kera.org/meyerson/wp-content/uploads/sites/12/2015/09/smallschrad-1409669095-51.jpg)

Budgeting And Bargaining | After he was appointed the administrative construction manager for the DSO, serving as liaison with the city, George Schrader says he went to Dallas’ public works department with concerns about the concert hall’s budget. “And they said, ‘Oh my yes, way over the budget, let’s just go ahead … toss the bids out and start over again. We can’t understand why the symphony continues to pursue a symphony hall of this cost.’ I went to the symphony, and they said, Leonard Stone [executive director of the Dallas Symphony Association] said, ‘Oh my yes, we don’t know why the city didn’t control costs long ago.'” Schrader learned what the symphony knew – that the $28.6 million was a figure chosen by city officials (ultimately with the symphony’s agreement) because it could get approved by Dallas voters. It had little relationship to what was being planned or what was needed.

A bare-bones building plan was the result. Bricks and mortar would be used instead of limestone, carpeting instead of marble floors. Architect I. M. Pei removed an entire top floor from his original design. But even that stripped-down version would cost more than the bond figure permitted. When word got out, it made the symphony look as though it had gone over-budget by 50 percent.

Later, many ehancements were put back in – but only as patrons donated money. This put the symphony in the awkward position of struggling to keep costs down to avoid more negative publicity – at the same time, its patrons were demanding only the best. The result: Some Dallasites still believed the Meyerson was over budget even as the symphony was purchasing African cherry wood for the balcony fronts and having Italian marble flown in specially by American Airlines.

All of this media glare demonstrated another wrinkle in the public-private partnership. Non-profit arts groups usually try to be discreet as possible about donors and money matters. But with the city involved, the symphony’s business was public business. City Council members – as was their fiduciary responsibility – picked over point by point in the budget and what the final cost would be.

A Million Here, A Billion There | Over the years, just what the Meyerson Symphony Center eventually cost has been the subject of debate. In 1989, the symphony’s official price tag is (and remains) $81.5 million – that’s both public and private funding. But that figure excludes land acquisition, infrastructure and debt service, which put it more like $138 million. That higher figure still does not include Betty Marcus Park (alongside the Meyerson), the Arts District garage (which the city mandated and which actually serves several organizations), plus the symphony’s own garage (140 spaces reserved for DSO staff and guests, costing $8.7 million). Add those, and the Meyerson nudges closer to $200 million, without factoring in inflation to make it reflect current costs. The Meyerson was built a decade before Frank Gehry’s Guggenheim Bilbao and the resulting Bilbao Effect. This refers to the acclaim and tourist revenue a city receives when it builds an architecturally glamorous arts venue, thus “iconizing” it, raising it like Bilbao, Spain, above other cities neglected by international media attention. That’s what the Meyerson did to a lesser degree, pre-Bilbao. But post-Bilbao, the effect takes off, with ambitious cities jacking their cultural building budgets through the roof. In 2015, the Philharmonie de Paris is set to open with a half-billion dollar budget. Hamburg’s Elbe Philharmonie (above) may break one billion when it opens in 2017. Both have been the subject of lawsuits, delays, changes in governments and/or public outrage over their costs. What’s more, the once-touted Bilbao Effect has faded in recent years – and whether it ever created a lasting cultural or financial impact on a city has been argued. When everyone has their own dazzling arts showcase, it may require a billion-dollar budget to get noticed.

International acclaim

Nothing succeeds like success – which is probably engraved somewhere as the Dallas city motto. The Meyerson gained international acclaim for its architecture and acoustics. The city got a boost – and so did the DSO. As can happen with a major new arts faciliity, the resident group was challenged to step up its game. The orchestra, which had barely survived the 1970s, was soon setting season subscription records and touring Europe. In particular, one reason the push for a new home for the DSO got underway was the orchestra’s inability – when it was still housed at Fair Park – to attract a significant European conductor. That changed in 2008 with the appointment of Jaap van Zweden as music director.

But the development of the Meyerson left other legacies. Dallas’ public-private partnership to fund arts facilities continues – but in an extremely pared-back fashion. Nothing like the concert hall’s 60-40 split exists. In recent years, the city has seriously reduced the maintenance and program budgets for its culture centers. And in 2009, twenty years after the Meyerson debuted, the doubly-ambitious AT&T Performing Arts Center opened. This time, public tax involvement was deliberately kept to a minimum. Ninety percent of the PAC’s $354 million cost came entirely from private donors.

There have been changes in the DSO as well – in its outreach, in the audience it tries to bring to the Meyerson. When asked what he thinks of the symphony center today – and how it represents Dallas – Domingo Garcia says, “I think it’s a great venue. I’m glad they’ve made efforts to diversify the crowd that they reach to, that it’s not just the top one-percent.”

Reviews from Opening Night