The Future

Step into the Meyerson Symphony Center today and it seems to have barely aged. In performance, the acoustics remain fresh and alive. I. M. Pei’s late-modernist design has an abstract grandeur that can still impress with its sweeping lines and swirling bars of light. Laurie Shulman, author of a history of the Meyerson, says simply, “This is a building that was built for the ages. And if properly maintained, it will only get better with time.”

But looking back at the hall’s first 25 years inevitably raises the question: What will the Meyerson be like in the next 25? It’s plain the future of the concert hall is tied to the future of the Dallas Symphony and to classical music itself. The Meyerson wouldn’t even exist without the DSO.

On that score, the orchestra’s music director, Jaap van Zweden, has been working on his own plan for the future: “If we are going on as we do now, I predict that this orchestra will be seen as – you know, we were talking of the top five [orchestras] in America. And I think that they will have to add a number. And that’s Dallas. And that was always my goal.”

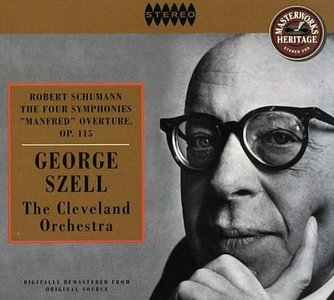

Who’s on Top? | Traditionally, the “Big Five” American orchestras are – alphabetically – Boston, Chicago, Cleveland, New York and Philadelphia. The list was compiled based on recordings, touring, size of audience and budget, international stature of conductor, etc. For example, Cleveland, by far the smallest, was included mostly because of George Szell’s presence at the podium (left). Yet the list was more than just a handy scorecard. The Big Five managers actually held summit meetings. And touting this many high-quality orchestras improved American prestige in classical music when it was still mostly a European (and immigrant) art form. Crucially, Big Five members were able to hire the best musical talent — thus creating a circular proof of orchestral quality. The best can hire the best therefore they’re the best. But early on, the rise of the Los Angeles, St. Louis and San Francisco orchestras caused their advocates to ask, why not a Big Six? Why a Big Five at all? Who decides on membership? In the past two or three decades, many of the assumptions behind the Big Five have been cast into doubt – with the growth of the Sunbelt (increasing the appeal of new cities for top hires), the upheaval in the recording industry and the financial downturn across the field (the Philadelphia orchestra filed for bankruptcy in 2011). Their aura of artistic predominance may linger (who would argue that these are not among our finest orchestras?), but this may be a rather old-fashioned club to join. In short, the Big Five looks to be the accepted wisdom of a specific era, that’s all. Here’s an intelligent overview from the New York Times.

Who’s on Top? | Traditionally, the “Big Five” American orchestras are – alphabetically – Boston, Chicago, Cleveland, New York and Philadelphia. The list was compiled based on recordings, touring, size of audience and budget, international stature of conductor, etc. For example, Cleveland, by far the smallest, was included mostly because of George Szell’s presence at the podium (left). Yet the list was more than just a handy scorecard. The Big Five managers actually held summit meetings. And touting this many high-quality orchestras improved American prestige in classical music when it was still mostly a European (and immigrant) art form. Crucially, Big Five members were able to hire the best musical talent — thus creating a circular proof of orchestral quality. The best can hire the best therefore they’re the best. But early on, the rise of the Los Angeles, St. Louis and San Francisco orchestras caused their advocates to ask, why not a Big Six? Why a Big Five at all? Who decides on membership? In the past two or three decades, many of the assumptions behind the Big Five have been cast into doubt – with the growth of the Sunbelt (increasing the appeal of new cities for top hires), the upheaval in the recording industry and the financial downturn across the field (the Philadelphia orchestra filed for bankruptcy in 2011). Their aura of artistic predominance may linger (who would argue that these are not among our finest orchestras?), but this may be a rather old-fashioned club to join. In short, the Big Five looks to be the accepted wisdom of a specific era, that’s all. Here’s an intelligent overview from the New York Times. But what does that even mean – when many orchestras are in a crisis? Classical music in America has a long history of fretting over its decline and fall, but the past decade has seen the field battered by an unprecedented onslaught.

Several major orchestras have suffered through bankruptcy, lockouts and cutbacks. Conventional classical CD releases are becoming a thing of the past. The DSO itself has suffered million-dollar deficits. In 2011, it nearly maxed out its line of credit – the money it draws on to pay its bills. A city’s cultural prestige may have once been tied, in part, to its symphony orchestra but with digital pop culture taking over the planet, much of traditional “high art” has lost its clout. Today, a leading video-game designer may bring more to a city.

The Next 25 years?

So in 25 years, will there even be an audience coming to hear classical music in the Meyerson?

“If we’re lucky, it’ll be a broader audience, a more diverse audience,” says DSO president Jonathan Martin. “Gone are the days where orchestras could be funded by the one percent. And so if we’re going to be around 25 years from now, it’ll be because we’ve elevated the value that we’re delivering back to the community. You know, 40 percent of Dallas identifies as Latino. How does that shape our programming? How does that shape our community engagement?”

Right now, any future concertgoers are young students. And they are being bombarded by more music through more outlets than any previous generation. Classical music is just one, tiny choice in a global world of sound.

Yet it’s a choice many young people never hear. They’re not exposed to classical music in their schools. Carlos Vargas thinks that’s a shame. When the 20-year-old cellist was at Booker T. Washington Arts Magnet High School, he was one of the few Latinos studying classical music. And he credits that and the DSO’s Young Strings program with changing his life.

“Once you get your Young Strings teacher,” he says, “you make this bond with them. They keep you grounded and keep you from making bad choices. Being exposed to this was the best thing that ever happened to me. So I think, the earlier the better.”

The DSO has a range of educational and outreach programs, but Young Strings offers more than free concert tickets or music classes. For qualified Latino and African-American students, Young Strings provides personal mentoring. Summer music camps are a possibility as well as loaned instruments, if students can’t afford one. And all this is free.

Dwight Shambley is a principal bass with the DSO and co-founder of Young Strings. He is also one of only two African-Americans in the symphony – a percentage that sadly persists for the entire industry. “The orchestra should belong to the city,” he says, “and the city should have ownership of the hall. What we’re looking at – with the Young Strings program – is broadening the base.”

As Jonathan Martin likes to point out: If you look at the demographic changes that are happening in America, you’re looking at Dallas. The city’s growing population represents the future spectrum of the U.S. population. So it’s not surprising that Martin developed the new ReMix series, which presents more contemporary music. And next May, the DSO will launch its Arts-District wide Soluna Festival – like ReMix, an attempt to present a fresher, more youthful take on classical music.

“If classical music remains a museum piece,” says Nathan Myers, “then we really will lose people.”

Myers is the director of opera for Booker T. Washington. Much of his effort, he says, goes into convincing students, who have no experience with classical music at all, just to give it a chance. He recalls taking kids from another DISD school to a concert.

“They had never even really been in there,” he says. “As a matter of fact, because my last name is Myers, they thought I was joking when I said we were going to the Meyerson. They’re like, ‘Yeah, right, Mr. Myers.’ But we got there, and they read it, and they say, ‘Wait a minute. Oh, so it’s a real place.’”

Students like these can easily find the entire classical music experience intimidating . For all the talk about music as a universal language, a classical concert is a daunting and unusual experience – especially in our fast-forward, short-attention-span age and especially for people who can’t afford it. We pay top-dollar to sit silently for an extended period of time in a huge room, a hall designed solely to resonate with the live sound of a large group of highly-trained artists, artists who often play music originally created centuries before in another language, music that follows now-obscure forms and conventions. It’s little surprise young people can feel out-of-place. We don’t expect them, upon first seeing an Olympic pentathlon, to understand what’s going on, how these matches are scored, let alone who’s winning.

Getting comfortable

That’s why Myers thinks the students’ first exposure to classial music is all-important. When his female students are going to attend their first opera and don’t have anything to wear to such an occasion, Myers will even dip into the school’s opera costumes for them. Anything so they won’t feel inferior.

Whether any of this succeeds depends on the definition of success. For example, those students of Myers who had never even heard of the Meyerson? “They were just so overwhelmed by the experience,” Myers says. “And I think that whether or not they decided to go into classical music afterwards, they have a personal relationship with it. They have an experience that they can recall that’s a positive one.”

So, if some of those students return to hear a concert at the Meyerson in 25 years, will it even be here? It’s not a rhetorical question, not in a city that’s seen the budget for cultural centers repeatedly cut in recent years. Jonathan Martin points out that the factor author Laurie Shulman mentioned earlier – “proper maintenance” – that factor’s going to loom large soon.

“The hall is now 25 years old,” he says, “and the lighting, the heating and ventilation and air-conditioning – they’ve come to the end of their useful life.”

What’s more, as a concert venue, the Meyerson was built for a pre-digital age. So the upgrades Martin seeks go beyond giving the hall’s air conditioning some new coolant.

Whatever else it may be, the Meyerson Symphony Center remains the biggest, most expensive musical instrument the Dallas Symphony has ever had. If, in 25 years, the DSO can no longer find an audience to fill it, then Dallas will have built and lost a Stradivarius.