“And you could hear the audience just gasp,” Kitzman says. “I remember that to this day, it was an amazing moment.”

They gasped because it was the first time a Dallas audience could really hear the orchestra. And, Kitzman says, it was the first time in Dallas she could really hear it as well – while she played. In the DSO’s old home, the Music Hall at Fair Park, the acoustics were muddy. In comparison, the clarity and warmth in the Meyerson were immediately apparent – apparent to that opening-night audience and to the critics and musicians who have, over the years, hailed the hall as a remarkable classical-music venue.

Diane Kitzman.

DSO music director Jaap van Zweden says one sign of the Meyerson’s acoustic quality is its pianissimo – the quietest notes, the notes at the lower limit of human hearing: “If you whisper in the hall, you can still hear it clear. And that is actually a quality only for the really great halls in the world.”

The Big Gamble

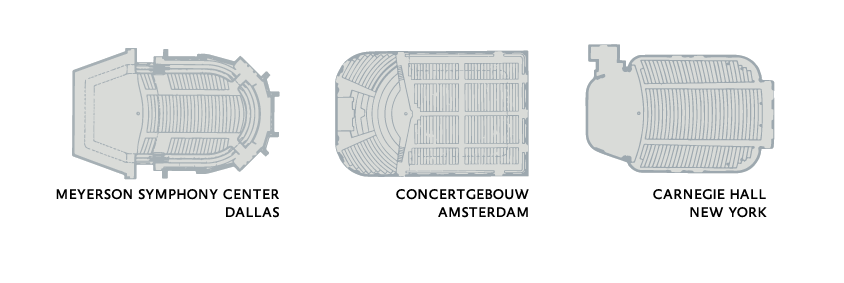

The Meyerson was consciously modeled on those great old halls – like the Concertgebouw in Amsterdam and the Musikverein in Vienna. During the planning phase for the Meyerson, a committee from the DSO toured Europe and came back with precisely those examples in mind. All the great old concert halls – Carnegie Hall, Boston’s Symphony Hall – were built a century, a century-and-a-half ago, built before inventions like steel girders, air-conditioning and electric amplification. Those modern blessings let halls get bigger, safer and more flexible, able to stage things like a Broadway musical one night and a high school graduation the next (thus making them more cost-effective, more revenue-generating).

But that’s also why many modern halls have dreadful acoustics. For years, experts knew some things about why the old halls sound so much better, but they were far from certain how to replicate their results precisely. One reason, says acoustics designer Nicholas Edwards, is that we don’t have any acoustical failures from the 19th century. If a concert hall sounded bad, it was eventually torn down or replaced. So acoustics experts today have a very small sample of successful halls to study. Even if the experts could have unlocked all of those old halls’ secrets, it would be cost-prohibitive to recreate exactly something like the Concertgebouw today.

Sound decisions

Which is why, in 1980, when the DSO set out to build a contemporary concert hall to rival the best in Europe, they were taking on a major challenge. For its acoustics designer, the DSO hired Russell Johnson and his New York company, Artec Consultants. And that was a gamble as well.

They were not exactly a well-established firm with an impressive resume. “They were working out of this apartment, and they didn’t really have many projects,” Edwards recalls. When he started working with Artec in 1979, he was only the fourth person on staff.

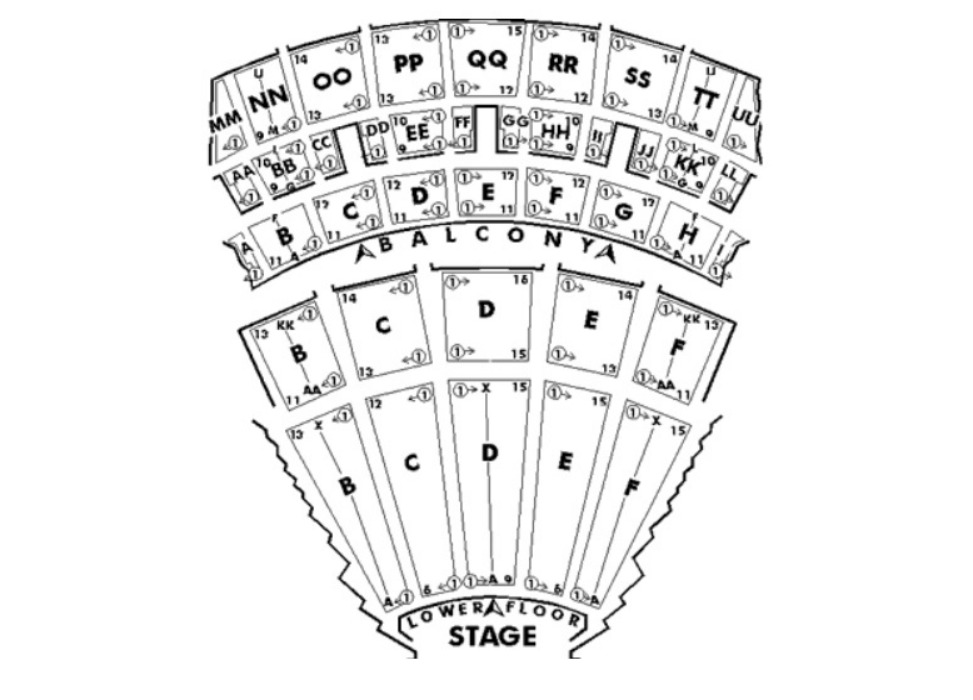

Concert Hall Acoustics in a Nutshell | The older concert halls that DSO committee members were so impressed with – Concertgebouw, Musikverein, Symphony Hall in Boston – are all 19th-century buildings with high ceilings, a shoebox shape, narrow balconies along the sides, thick masonry walls and a limited number of seats (only 1,700 in Vienna). Influenced by the era’s economics and construction technology, these halls hit upon an excellent formula for concert acoustics. But with the advent of steel structures and electric amplification, halls got bigger and abandoned the shoebox for a fan shape. The fan permits better sightlines and a more economical, flexible, multi-purpose layout – it is, in fact, the layout of the DSO’s previous home, the Music Hall at Fair Park (above, left). But the fan suffers from the ‘megaphone fallacy’ – the idea that an audience hears an orchestra only from the stage, directly in front of the listeners. Despite what our brains tell us, we listen in stereo with our two ears, and our brains pick up all the variations of the sound as it’s reflected back at us at different times from the side, celing and back. Simply copying the older halls to achieve great acoustics is not feasible today because of costs, fire regulations, handicapped access, our preferences for more restrooms, roomier seating. Finding a contemporary, economically affordable way to replicate those halls’ acoustics became the holy grail for acousticians. Russell Johnson thinks he can do it. Dallas’ new concert hall is a huge gamble that he’s right.

Concert Hall Acoustics in a Nutshell | The older concert halls that DSO committee members were so impressed with – Concertgebouw, Musikverein, Symphony Hall in Boston – are all 19th-century buildings with high ceilings, a shoebox shape, narrow balconies along the sides, thick masonry walls and a limited number of seats (only 1,700 in Vienna). Influenced by the era’s economics and construction technology, these halls hit upon an excellent formula for concert acoustics. But with the advent of steel structures and electric amplification, halls got bigger and abandoned the shoebox for a fan shape. The fan permits better sightlines and a more economical, flexible, multi-purpose layout – it is, in fact, the layout of the DSO’s previous home, the Music Hall at Fair Park (above, left). But the fan suffers from the ‘megaphone fallacy’ – the idea that an audience hears an orchestra only from the stage, directly in front of the listeners. Despite what our brains tell us, we listen in stereo with our two ears, and our brains pick up all the variations of the sound as it’s reflected back at us at different times from the side, celing and back. Simply copying the older halls to achieve great acoustics is not feasible today because of costs, fire regulations, handicapped access, our preferences for more restrooms, roomier seating. Finding a contemporary, economically affordable way to replicate those halls’ acoustics became the holy grail for acousticians. Russell Johnson thinks he can do it. Dallas’ new concert hall is a huge gamble that he’s right.Scroll to make the reverb doors open and close.

Sound and Fury

In addition to the reverb chamber, a flying canopy was installed over the stage. The heavy, four-part canopy lowers the ceiling – the central section alone weighs 42 tons. (Its shape and lights have earned it the nickname “the Starship Enterprise.”) While the reverb chamber expands the total airspace for big, orchestral and choral works, the canopy shrinks it, making the hall more suitable for chamber music.

These moving parts are fascinating – they demonstrate the Meyerson auditorium is not a static room, it can be played like a musical instrument. But they’d been used before in other halls. The real innovation in the Meyerson, surprisingly enough, was simply the auditorium’s shape. The great old halls were built like shoeboxes. The Meyerson is more rounded than that; it opens out from the stage, then narrows back in again at the back. But the shape has much the same effect as the earlier shoebox. It helps reflect sound from the sides and the back to the listener.

Edwards says, the result in the Meyerson is “this sort of three-dimensional sense, this envelopment, this involvement in the music.”

But the shape of a hall is a decision traditionally made by the architect. In this case, that was the great I. M. Pei. The Meyerson may have been Pei’s first concert hall, but Pei was a long-established and highly-respected name in architecture – while Russell Johnson was a comparative unknown. Yet in an unusual move, the DSO gave Pei and Johnson equal authority. The Meyerson committee did it to emphasize how important they regarded the acoustics.

Inevitably, perhaps, the two men disagreed over almost every detail. That’s partly because they were both trying to control the same things: the shape and make-up of the Eugene McDermott Hall inside the Meyerson.

Even if Russell Johnson and I.M. Pei had not been hired as equals, their relationship would probably have been strained: Johnson had been tenacious in getting his job and had lobbied that he be in charge. Even with both in charge, Pei had to accept the general shape of the auditorium – before he designed anything. To Pei’s regret, the interior was going to be conservative-looking compared to his designs for the lobby and exterior. Other points of contention between the two included the canopy, which the Pei office objected to. Johnson dismissed one choice of seats (too soft, too acoustically absorbent). A German company offered the best seats, but Pei rejected them as ugly. Ultimately, only one American company could deliver the required seating on time. Pei wanted the giant columns that flank the stage – they give the impression they’re ‘supporting’ the overhanging reverb chamber along the top of the hall. Johnson claimed the columns would be detrimental to the hall’s acoustics. Pei wanted the reverberation chamber to be hidden by a latticework grill. Johnson feared the material would muffle or alter the sound. As a test, temporary grills (above) were built and installed for $65,000. They remain there to this day.

Pei wanted to disguise the reverb chamber, for instance; Johnson objected, fearing any kind of cover would affect the sound.

There may have been fireworks between the two, but Edwards says the results were a classic case of creative tension. Working in tandem, the two got so much right in both the looks and the sound of the Meyerson. “What’s astonishing about Dallas,” says Edwards, “is that it managed to pull off both of those, great architecture and great acoustics.”

It’s typical of the Meyerson, for instance, that what can seem weaknesses turn out to be strengths – the way the auditorium feels so surprisingly different from the lobby, for example. Pei always felt the auditorium was too conservative, and this actually freed him up more with the lobby. Pei is a master of sharp, clean, abstraction. He likes to use a building’s structural elements as design elements, exposing them to underscore the building’s geometry. Recall his celebrated “glass pyramid” at the Louvre or the prism-like facets of the Fountain Place tower, half-a-dozen blocks away from the Meyerson. They’re all pure, sleek, shapes, a hallmark of the best late-Modernist style.

For the Meyerson, Pei gave the lobby a grand scale – it’s vastly larger than the lobbies in traditional, European concert halls. And Pei made that space spiral and spin like an armillary sphere. It’s a glorious bundle of sweeping curves and radiating ellipses, played against the hard, flat surfaces of stone walls and floors. If this crisp, cool style continued into the auditorium itself, a concert there would be a chilly experience (and an acoustical nightmare).

“The magic”

Instead, we get what DSO president Jonathan Martin calls “the magic” of the two spaces interacting. The lobby’s clattery acoustics, for example, can animate a crowd’s energy and chatter, while the auditorium – with its warm wood, dusky seats and amber lighting – can feel soothing and even, despite its size, intimate. The room is more cozily conventional than the lobby; probably the only things that will date the Meyerson are the hall’s rather ’70s-ish color scheme and ‘classy’ touches. But Dallas Morning News classical music critic Scott Cantrell has called the entire experience of attending the Meyerson a kind of theater, a three-act play. We step from the low-ceilinged parking entrance up to the grand staircase, and we suddenly emerge, as if from a dark cave, into this high, airy rotunda with its bright, intersecting arcs. It’s like something out of the Enlightenment: open, precise and beautifully rational. Then – as if to amplify the musical experience to come – we finally enter McDermott Hall with its hushed, velvety welcome.

All this, before a single note is heard. There are plenty of performance halls that excite but only up to this moment, only until the conductor raises his baton. The Sydney Opera House and Avery Fisher Hall at Lincoln Center have been infamous examples of this – visual grandeur followed by acoustic letdown.

Just for fun, watch the Meyerson dance. Video by Dane Walters

So we’re back to the Meyerson’s sound and whether the long-sought, roll-of-the-dice goal to match the finest European concert halls was achieved.

Jaap van Zweden, the DSO music director, is in a position to judge. He was the concertmaster, or lead violinist, at the Concertgebouw for 16 years. He’s lived in some of those great old halls.

The Meyerson, he says, is “like a combination of the Concertgebouw and the Musikverein. The Musikverein in Vienna is a little smaller, and the Concertgebouw is a little bigger.

“So my experience is that it is actually from both worlds the best.”