The Organ

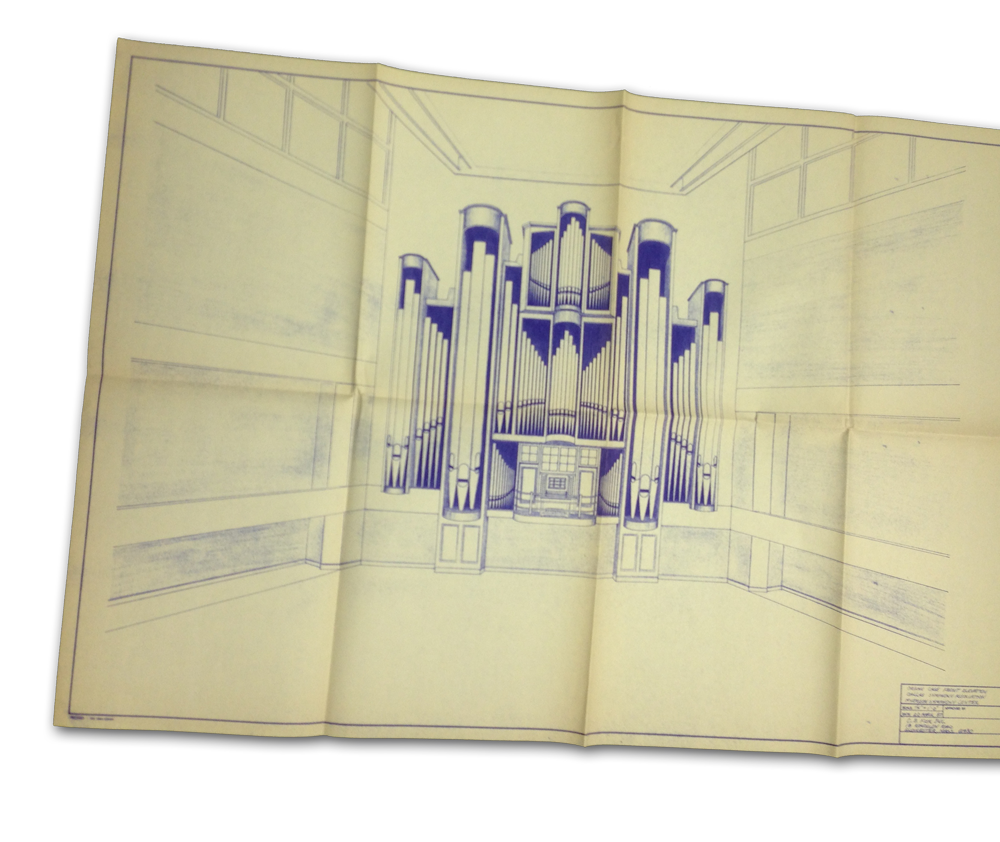

Critics say the organ inside the Meyerson Symphony Center is one of the greatest. And its acclaim inspired organ installations in concert halls around the world.

The Lay Family organ made its debut in 1992, three years after the Meyerson opened. Camille Saint-Saens’ Organ Symphony No. 3 capped the inaugural concert. This masterpiece is the rare classical work that almost perfectly marries the organ and the orchestra. And on that night, Dallas heard a new instrument almost perfectly matched to its home.“The Lay Family Organ at the Meyerson Center is one of the great organs of the world without question, in one of the great halls.” says Michael Barone. He’s host of the award-winning radio show Pipedreams.

“What makes the hall wonderful is that its acoustics are adjustable, and can be made quite extravagant. And when opened up to the full, the resonance chambers really do make quite a splash of sound.”

Sound You Can Feel

Watch Mary Preston play the Finale from Mendelssohn’s Organ Sonata No. 1

That resonance thrills audiences and makes the organ sound like it’s been lifted out of a grand European Cathedral, says Dallas Morning News critic Scott Cantrell.

“The more reverberation there is the more they like it. So in a solo recital you can open up all those reverb chambers and get this incredible swim of sound there, although it never gets muddy.”

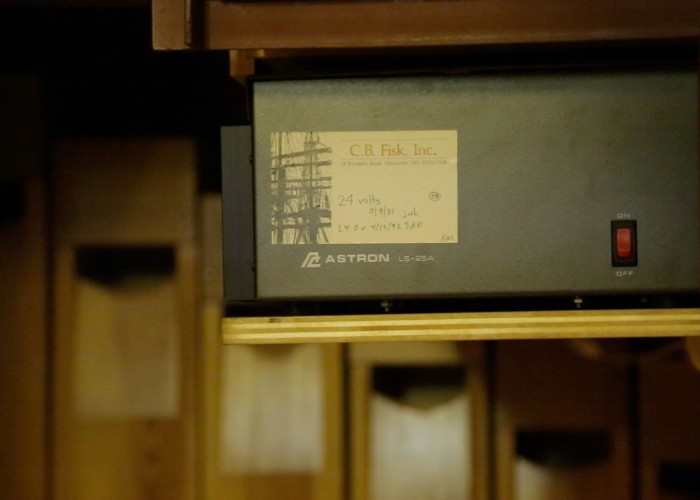

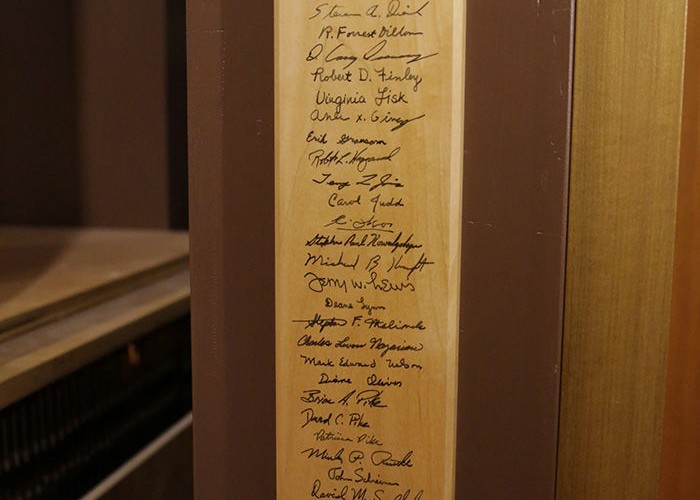

The Dallas Symphony’s organist Mary Preston praises builder, C.B. Fisk, for that accomplishment. “This is a glorious instrument because each of the stops is very pure. Each of the sounds of the ranks of pipes are very pure in and of themselves.”

Preston has played with the DSO for 20 years. “Some organs,” she says, “in order to get a pretty sound, you need to pull out a whole bunch of stops, meaning engage a whole range of pipes. On this instrument it’s not so. This instrument has beautiful sounds each and every one of them.”

Thousands of pipes

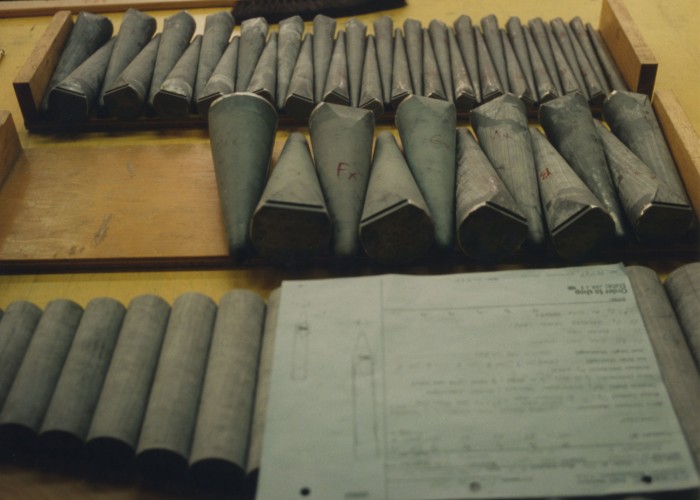

Preston says that purity comes from the pipes. You can see 70 of them in the hall. The rest, more than 4000, are crammed into a 6-foot deep space behind the organ console.

The smallest pipe’s about an inch long. The 32-foot tallest pipe is so big a person can stand up inside it. It can play a note a full octave below anything the orchestra can.

“Even when you don’t quite hear it, there’s just this low rumble that’s not so much a pitch but an experience,” says Michael Barone, the radio host. “When the full organ is going, when you pull on the big 32-foot Bombard, it’s not just the sound. It’s the “wow” impact of the sound vibrating your whole body.”

So why don’t we hear it more?

“It would be wonderful if we could play it more,” says Preston.

Critic Cantrell is a little more emphatic: “People want to hear this instrument. There it is. It’s right at the front of the hall. It’s an enormous presence. People often ask me does it ever get used? And I have to say, well, almost never.”

There was an international organ competition. Launched in the 90s, three were held, then the competition’s top champions retired or moved away. An ailing economy helped kill it.

But change may be coming. The orchestra plans to program more selections that include the organ. And this coming season, the symphony will re-launch an organ recital series that includes three concerts with international soloists. Jonathan Martin, DSO President and CEO, says it will include three concerts with international soloists.

“You know, we’ve got this great car in the driveway and we need to take it out and drive it more,” says Jonathan Martin, DSO President and CEO.

The King of Instruments

Barone believes the effort will pay off once people open up to this monster that Mozart called the King of Instruments, and realize the organ, which predates Christianity, isn’t just for church.

“It is the most complicated of musical instruments and yet to be able to make it sing, to make it touch your heart, to be able to create emotions with this machine is quite magical.”