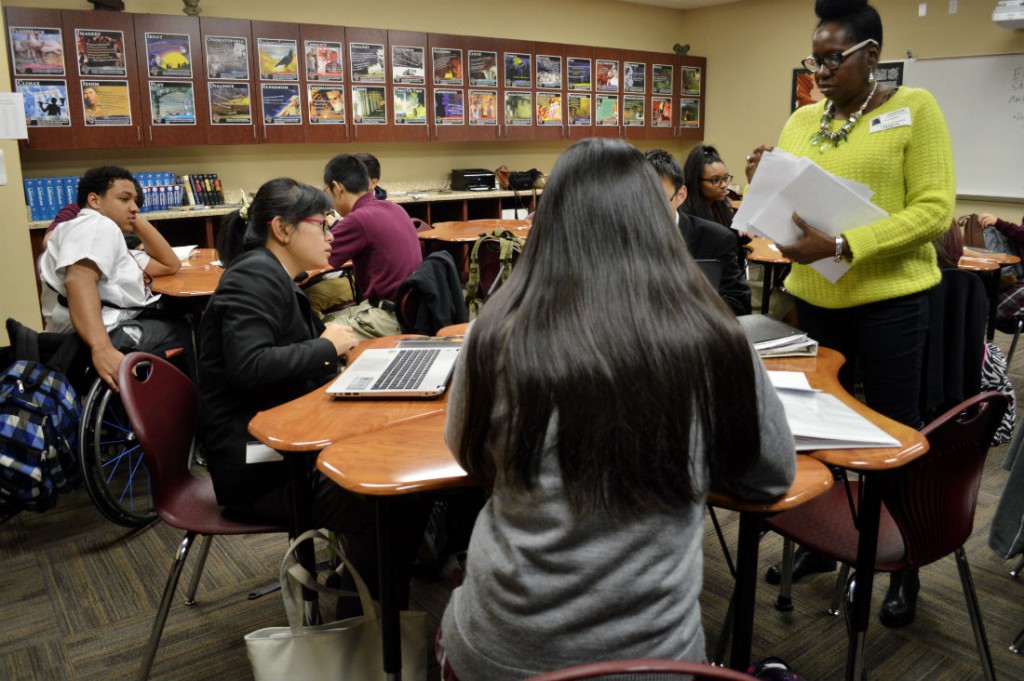

Students study at International Leadership of Texas in Garland. Photo/Christina Ulsh

Students study at International Leadership of Texas in Garland. Photo/Christina Ulsh

Leaving Mom And Dad Behind In China For School In The U.S.

A decade ago, about 600 Chinese students attended high school in the United States. Today, there are more than 38,000. For many, this is their first time away from home and their first time in a new country. Meet one teen who’s making the transition at a Garland charter school.

Niuying Cao, center, and other students from International Leadership of Texas pile into a school van after going grocery shopping at a Chinese store in Plano. Photo/Christina Ulsh

Every other weekend, Niuying Cao and her classmates pile up in a large, white van and head to 99 Ranch Market. It’s a bustling Chinese supermarket in a Plano shopping center.

More than 7,000 miles away from China, it’s a small reminder of home for the 10th grader, who goes by Arron.

Well, sort of.

“It’s different from there,” Arron says. “It’s much different from China. A bit like China.”

From left: Jiaying Zhang, who goes by Shirley, and Niuying Cao, who goes by Arron, go shopping at 99 Ranch Market in Plano to stock up on treats and drinks that remind them of home. Photo/Christina Ulsh

At the store, she joins another student, Jiaying Zhang, who goes by her American name, Shirley. They grab a shopping cart and walk up and down the aisles.

Arron, who’s 17, is from Shanghai. She’s one of 28 students who arrived in August to attend International Leadership of Texas, a public charter high school in Garland.

The teens live on campus in new apartments. During the week, they have wake-up calls at 6:10 a.m. It’s lights out by 10 p.m. Sunday through Thursday. But on the weekend?

“In China, if I get up late, I’ll always have my breakfast,” Arron says. “But here if I get up very late, maybe the breakfast was cold. But in China, my mom will do that.”

She laughs.

In U.S., Chinese student population keeps growing

Overall, the number of Chinese international students at American schools has grown during the past decade, according to the U.S. Department of Homeland Security. In 2005, just 632 students attended private and public high schools in the U.S. Today, there are more than 38,000.

Gary Manns is the director of international students at International Leadership of Texas in Garland. “I’m like their second dad,” he says. Photo/Christina Ulsh

Gary Manns is the director of international students at the International Leadership of Texas and the students’ guardian.

“I’m like their second dad,” he says. “I make sure they’re fed. I make sure they’re in bed by a certain hour. I get ‘em up in in the morning.”

Manns spent two years teaching in China. His wife is Chinese. The couple live on campus with the students and spend a lot of time with them. Manns stays in touch with the kids’ parents using a voice and text messaging service called WeChat. He also takes them on the weekend shopping trips.

“I was taking them to NorthPark [Center] and things like that, but their parents want me to kinda slow down on the shopping things,” Manns says. He laughs. “These kids were buying expensive items. So, right now, we’re just doing the Wal-Marts and Chinese markets.”

Niuying Cao, who goes by Arron, sits in front of a laptop and gets ready to take a language arts open-book test. Photo/Christina Ulsh

Some come for high school — and stay for a lifetime

Sending your child to the U.S. for an education is not cheap. Those who come typically are from middle- and upper-class families. The students at IL Texas are paying $28,000 a year, which includes health insurance, a laptop, an iPhone and room and board.

At International Leadership of Texas, teens live on campus in new apartments. During the week, they have wake-up calls at 6:10 a.m. It’s lights out by 10 p.m. Sunday through Thursday. Photo/Christina Ulsh

Once they graduate from high school, many will stay in the U.S. to attend college.

“I think a lot of them see American universities as better universities to prepare their children — for future careers and goals,” Manns says.

Once they have that degree, Manns says many will try to land jobs in the U.S. and stay here permanently.

In the meantime, the goal is to master English. A lot of the kids know a little bit when they arrive. In class, teachers have to speak slowly and use visuals, showing them pictures of words.

‘Like a new world’

Shirley, who’s 16, says it can take some time to get used to living in a foreign country. Shirley compares it to a classic adventure tale: Alice in Wonderland.

Arron isn’t only learning English; she’s having to learn to adjust to American classroom life, including students who wear makeup. Photo/Christina Ulsh

“Everything is new and it is different from China in some ways,” Shirley says. “It’s just like a new world.”

It’s a new world where teens have much more independence. That was surprising to Arron. For example, the kids wear makeup at school.

“In China, if you wear makeup every day, you were in trouble,” Arron says.

In China, girls also get in trouble if they wear their hair up, Arron says. It’s quite a contrast to how she typically dresses. Manns points this out on a recent Friday at school.

“Even today, today’s a casual day for kids,” Manns says. “They can wear polos, whatever. She’s got her blazer on.”

From left: Niuying Cao, who goes by Arron, records classmate Jiaying Zhang, who goes by Shirley, reciting a poem on her iPad to a customer at 99 Ranch Market. The assignment is designed to help students practice their English. Photo/Christina Ulsh

Practicing English everywhere

Still, there are some things it seems teens everywhere like to do. During this outing at the market, the girls stayed glued to their iPhones. Shirley even brought her iPad. At one point, Shirley approaches a photographer and begins reading some lines from her smartphone screen.

“So bashful when I spied her,” Shirley reads. “So pretty. She ashamed … “

It’s an Emily Dickinson poem. A few minutes later, Arron approaches a stranger and begins reciting lines, too, as Shirley records it on her smartphone.

Turns out it’s a class assignment to get the kids to practice their English.

The girls try not to laugh as they approach other people. One man says no. A woman says OK but, just as long as no one takes her photo.

When the teens are done shopping, they get into the van and head back to campus.

They say they’ll likely spend the rest of the afternoon studying with a break for dinner – catered Chinese food.

Arron leaves 99 Ranch Market in Plano with a bunch of goodies that remind her of China. Photo/Christina Ulsh

Learning Spanish, too

It’s not just English the students have to practice. At IL Texas, all of the kids are learning Mandarin Chinese.

Arianna Guevara, left, and Arron Cao take a picture together. Photo courtesy Arron Cao

They’re learning Spanish, too. Arron’s in luck. Each Chinese student is paired with a local mentor. Arron’s is Arianna Guevera, a 15-year-old who goes by Aria. She was born in Mexico and speaks Spanish.

The first time they went to Aria’s home, they made tostadas.

“I showed her how to prepare, how to put the beans and the lettuce and the meat of her choice,” Aria says. “At first, she had trouble because it’s not something usual for them to eat with their hands, and a tostada you eat with your hands. But then after she got the hang of it, she was like, ‘oh, this is really good. Yum.’”

Arron’s going to spend Christmas break with Aria and her family. On the menu? Tamales, posole, English, Spanish and Mandarin.