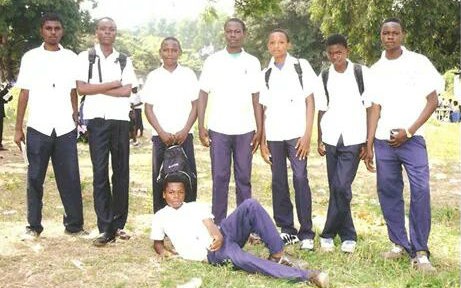

David Kapuku on his way to school. Photo/Mark Birnbaum

David Kapuku on his way to school. Photo/Mark Birnbaum

In A Land Of Strangers, Paving His Own Path

Just two weeks after arriving from Africa, David Kapuku enrolled at Conrad High School in Northeast Dallas. He started school in a new country where students speak a different language. It can be overwhelming. Now, a year and a half later, David is helping other refugee kids making the transition.

For David Kapuku, the first few months at school were rough.

He wasn’t just new to Dallas; he was new to the United States, arriving from the Democratic Republic of Congo.

The worst part for him and his three siblings? There weren’t many people they could talk to.

“We are frustrated the first day. You know?” David says. “Because I knew only French, so we didn’t know how to speak English.”

In the Dallas Independent School District, students speak more than 60 different languages. They come from 147 different countries. Sitting in the lunchroom at Conrad High was unlike anything David had experienced.

“In Africa, everybody’s, like, black,” David said. “It’s not like being racist. When we come here, we see, like, Mexicans. We see, like, people from Honduras. Like Nepalese, American people, so like everybody.”

When his family arrived in January 2013, David began studying, but not just homework. He watched other students to see how they acted and talked. He’d see teachers explain a lesson — he wondered what they were saying.

David is embracing his new life by singing in the school choir at Conrad High. Photo/Mark Birnbaum

‘I was so alone’

What’s it like being the new kid? Not that great, says David’s sister, Ruth.

“I was so alone,” said Ruth, who’s 14. “I was thinking to stay home, sleep and watch TV. That’s better than to go to school to not spoke with anybody. But when I learn to speak little bit English, now I think I like the school.”

David Kapuku, right, with his family in Northeast Dallas. Photo/Stella M. Chávez

For many immigrant kids, those first few days, even the first year, can be daunting.

At Conrad, an orientation for refugee helps ease the transition.

Marnie Tao, who teaches English to immigrant students at Conrad, leads a recent session in the school library. The teens hail from Burma, Somalia, Nepal and Iraq. One girl is in a hijab, the traditional headscarf for Muslim women. Several boys sport colorful soccer jerseys.

“Cultural acceptance is understanding that people all around you may be very different from you, but that’s OK and that’s a good thing,” Tao tells the students.

Tao rattles through details that affect all students, such as school uniforms, cellphones, attendance policies and detention.

She also talks about situations unique to immigrant and refugee students. Conrad hires interpreters for 12 different languages, including Somali, Arabic, Chin and Karen. The school counts green card appointments as excused absences.

Some of these students attended Tasby Middle School, which is in the neighborhood. Some know English.

But others may have never been to school in their life, Tao says.

“Maybe some of you guys have never been to school before Tasby, OK?” Tao tells the students. “Or they maybe only got to go to grade five before they had to leave their country.”

Last year, 1,300 refugee students were enrolled in Dallas ISD. Most are learning English. Many are poor.

In the Democratic Republic of Congo, David Kapuku would walk 30 minutes just to get to school. Today, he takes a much shorter walk on his way to Conrad High School in Northeast Dallas. Photo/Mark Birnbaum

‘I’ll be there to help them’

David, a junior, has become somewhat of a leader at Conrad. His English improved after he attended Saturday tutoring lessons. He also credits his English teacher. Now, he volunteers as a school guide for new refugee students.

“So you need to be here a little bit early to get in the front of the line,” David, 18, told some of the newcomers. “So everyone need to be in the line, then we go over there and take lunch.”

David Kapuku volunteers as a guide for refugee students at Conrad High School. Photo/Stella M. Chávez

David says these students are the future. When he was in their shoes, a native of Africa who spoke French showed him around. The student told him not to worry, that it would take time to learn a new language and feel more comfortable.

“That’s why I say I’m gonna be there to help other people like refugees or people who came here, but who doesn’t know how to speak English,” David says. “I’m gonna be there like when they don’t know how anything to do, even by sign or gestures. I’ll be there to help them.”

Zeljka Ravlija came to the U.S. 15 years ago as a refugee from Bosnia. Now she coordinates the district’s Refugee School Impact Grant. She says education can lead to role reversal in families. For David, that means translating for his parents.

“They are sometimes taking role of interpreter for the family or for the community, taking care of some family businesses such as food stamps, doctors’ appointments, banking business,” Ravlija said.

Hoping for a better future

David and his family live in Vickery Meadow, an ethnically and racially diverse neighborhood in Northeast Dallas. Vickery Meadow was in the international spotlight this fall after a Liberian man staying there became the first person to be diagnosed with Ebola on American soil.

The Kapuku family rents an apartment like they did back home. In Kinshasa, the capital of the Democratic Republic of Congo, the kids got up daily at 5 a.m. and walked 30 minutes to get to school. In Vickery Meadow, David is just a few minutes away and a short walk from Conrad High.

David Kapuku is a student at Conrad High School in the Dallas Independent School District. Photo/Mark Birnbaum

David says his parents came to the U.S. so he and his brothers and sister could have a better future.

“If we get our degree here in United States of America, it’s gonna be easier for us to find a job everywhere around the world,” David says. “Because, in my country, there are some people who got the degree, but they can’t find job. They can’t find job.”

By being in the United States, David feels he owes something to his family, and his country back in Africa.

“People are dying of hunger in my country. Life is not stable,” David says. “In my country … Yes, I was normal. But that normal is not the same thing that we are here in the United States of America. We need to be good persons so one day we can help our family; we can help everybody in my country.

“The United States is powerful. I believe that my country one day is going to be powerful also.”

David Kapuku talks with his father, Corneille, outside their Vickery Meadow apartment. Photo/Mark Birnbaum

A reminder of home

David’s parents were pastors in Kinshasa. Here, David’s dad, Corneille, works an overnight shift stocking items at Wal-Mart. His mom, Bernadette, works all day assembling products for Samsung.

Corneille and Bernadette Kapuku, David’s parents. Photo/Stella M. Chávez

Everyone in the family has green cards after David’s mom won the chance to become a permanent resident through the State Department’s diversity visa lottery program.

Corneille Kapuku says the long, grueling hours at work beats working in a politically unstable country. In Congo, millions have died in war – and others have died due to disease and malnutrition.

He speaks in French. David translates.

“The politics system, you know, in Africa — the president and all the staff, they are like a little bit tricky with the stuff they are doing, like bad stuff,” David’s dad says.

David is adjusting to his new life. He’s learning about architecture and construction.

He’s playing basketball. He’s in a robotics club. He’s attending college prep events — he wants to become an electrical engineer.

He also joined the school choir.

“I like when the combination of those voices makes a good melody,” he said. “You feel something inside you. When you sing, it’s really good.”

Sometimes, they sing in Swahili. It’s one of the languages spoken in his native land.

Eight thousand miles away from Congo, the song is a reminder of home.

One district, many languages

Kids in the Dallas Independent School District come from 147 different countries and speak more than 60 languages. Here’s a sampling of some of the languages that are spoken:

Source: Dallas Independent School District

Slideshow: Life in Africa

Africans in North Texas

- The foreign-born population from Africa has grown dramatically in recent decades. In 1970, about 80,000 Africans lived in the U.S. By 2012, it was about 1.6 million, according to the U.S. Census Bureau.

- Four states have an African-born population over 100,000 people. That includes New York (164,000); California (155,000); Texas (134,000); and Maryland (120,000).

- Dallas-Fort Worth is among the country’s metro areas with the largest African-born populations. North Texas ranks No. 6, with 61,000 people. New York City ranks first with 212,000. Washington, D.C. has 161,000; Atlanta and Los Angeles each have 68,000. Minneapolis-St. Paul ranks fifth with 64,000.

Source: U.S. Census Bureau

Slideshow: Scenes from Vickery Meadow

Vickery Meadow was in the international spotlight this fall after a Liberian man staying there became the first person to be diagnosed with Ebola on American soil. It’s an immigrant-rich neighborhood in Northeast Dallas. Take a look as kids from Vickery Meadow got ready for the first day of school.