Inside the International Newcomer Academy in Fort Worth. Photo/Christina Ulsh

Inside the International Newcomer Academy in Fort Worth. Photo/Christina Ulsh

In Fort Worth, A School Just For Immigrant Kids

There’s an innovative school in the Fort Worth school district with about 500 students. Not one of them has been in the U.S. more than a year or two. It’s called the International Newcomer Academy. Here’s a look at how this school works.

From left, Devanhy Lopez Fragoso and other students work on a social studies jigsaw vocabulary review at International Newcomer Academy in Fort Worth ISD. Photo/Christina Ulsh

At one table in a sixth-grade classroom, a boy from Afghanistan sits across from a couple of girls from Nepal. Next to them is a girl from Mexico.

They’ve all been in the United States for less than a year.

They’re all working as a team.

Their teacher, Jaclynn Santilli, talks to the class.

“This is where you show me if you can take what you remember from Monday, Tuesday and earlier today,” she says. “Read in English, speak in English, and write in English and work together to solve the puzzle.”

Santilli is explaining how to do what’s known as a vocabulary jigsaw. The kids are in groups of four; everyone gets a card containing a set of clues to help them figure out words. At this table, the phrase has something to do with demographics.

“Two words: The first starts with a B,” one student says.

When students interact with each other, they learn by hearing the information and sharing it.

This exercise also builds empathy, Santilli says, because kids realize they’re all going through the same struggle of learning a new language.

Jaclynn Santilli, a teacher at International Newcomer Academy, explains a vocabulary exercise to her sixth graders. Photo/Christina Ulsh

Feeling safe far away from home

Devanhy Lopez Fragoso, who’s 11, reads the next clue.

“The second word start with an R,” Devanhy says.

Finally, it clicks.

“Beert rate,” Devanhy says. “Bit rate. Look. Beert rate.”

Sixth grade students work in small groups and use clues to figure out their social studies vocabulary words. Photo/Christina Ulsh

She’s saying birth rate. Then a smile and a giggle. Just a few months ago, she and her family arrived from Monterrey, Mexico. She says she didn’t know English when she arrived.

Devanhy says school is different here. It’s hard. She struggles with pronunciation. And she wishes she could see all of her relatives like she did in Monterrey.

But there’s a bright side.

“Because here the school is, like, good,” she says.

Devanhy describes school in Mexico as ugly. She talks about the lack of security. Here? She feels safe. And that’s true of a lot of these 500 kids.

“In Mexico, is really bad, the situation – like economic, like the problem with safety,” said Yanet Hernandez, a ninth grader who’s 18. (A number of the students are much older than usual for their grade.)

Over and over, these kids talk about safety. Yanet’s mom didn’t want her only daughter to come to the U.S. at first. She tears up as she explains in Spanish.

“My mom didn’t want me to have problems,” Yanet says.

Gunmen held up her mom’s convenience store while they were both inside, she says.

They decided she’d be better off living with her aunt and uncle in Fort Worth.

Amanda Bradley is the dean of instruction at International Newcomer Academy in the Fort Worth school district. “We try to make sure that … they’re adding something to our school,” she says. Photo/Christina Ulsh

Nine dictionaries in nine languages

The school’s goal is to recognize a student’s home country, says Amanda Bradley, dean of instruction at the International Newcomer Academy.

“We understand they’re coming from war-torn countries and that they have a story that they want to tell,” Bradley says. “We try to make sure that … they’re adding something to our school and not just becoming an American but also that they bring a lot with them.”

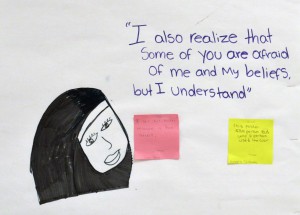

A ninth-grade English class made posters showing what they learned from “Behind the Veil,” a story about a girl who feels she’ll be judged for wearing a veil. Photo/Christina Ulsh

And that means getting creative. Recently, students read a story called “Behind the Veil.” It’s about a young Muslim girl named Nadia. Along one wall, students write their impressions of the story on sticky notes.

“They might not have the full vocabulary and when you read their work, it’s broken English, but that’s OK, you can tell that [they know] the concept,” Bradley says. “That big idea that we want them to achieve is there and that’s what we focus on.”

Most of the kids just spend a year here before going to their local middle or high school. There are about a dozen or so newcomer programs in Texas and more than 60 in the country.

Julian Vasquez Heilig, a national education researcher, says a visit to the Fort Worth academy convinced him that separate schools for immigrant students can work as long as they have high-quality teachers and innovative approaches.

“I was sitting at one of the tables and there were dictionaries – nine different dictionaries in nine different languages – stacked in the middle of the table,” he says.

This fall, teachers have been focusing on getting kids to pick up books on their own. In the first six weeks of the semester, 4,000 books were checked out, compared to a few hundred last year.

Yanet Hernandez, a ninth grader at International Newcomer Academy, arrived in March from Mexico. She wants to attend TCU. Photo/Christina Ulsh

Thinking beyond high school

Victor Cervantes, a student at International Newcomer Academy, came from Mexico a year ago. He wants to go to college and play football or soccer. Photo/Christina Ulsh

There are successes, but these kids have a long way to go. Last year, only two students out of 135 passed English 1 on the statewide STAAR test. This year, 11 did, principal Rodrigo Durbin says.

“These are brand-new students coming in, only been here eight months, nine months and their expectation is they’re gonna pass English 1, so it’s very challenging for our campus and especially those students,” Durbin says.

That’s why the school gives these kids opportunities they never imagined would be possible in their native country, Durbin says. Like thinking about going to college.

Yanet gets emotional when she talks about her plans after high school.

“Yo quiero ir a TCU,” she says in Spanish.

She wants to go to TCU.

After a visit to the Fort Worth college, she brought home a memento with her name on it.

It’s hanging in her bedroom. It’s a daily reminder of her ultimate goal.