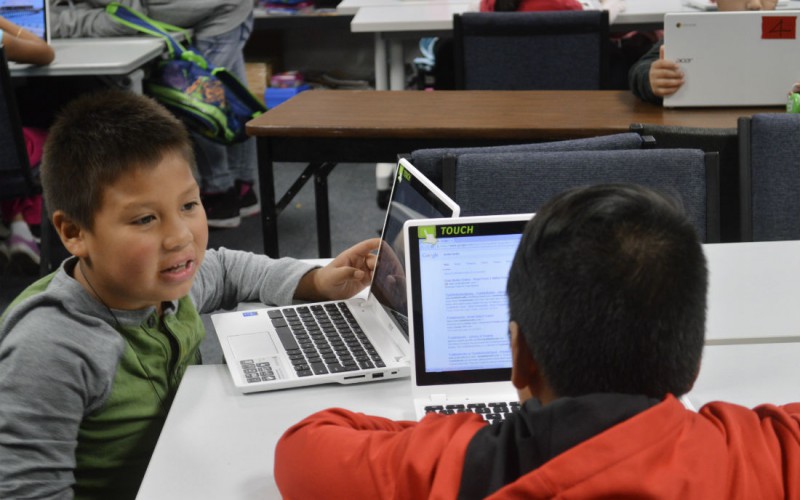

Inside the Language Assessment Center in Grapevine. Photo/Stella M. Chávez

Inside the Language Assessment Center in Grapevine. Photo/Stella M. Chávez

Going From Spanish (Or Urdu Or Arabic) To English

Immigration is transforming Texas and its suburbs. Take the Grapevine-Colleyville school district near Fort Worth. In the last decade, it has seen its overall student population shrink while the number of non-white students doubled. The number of students learning English — they’re called English language learners — has climbed 60 percent. How are the schools responding to this change?

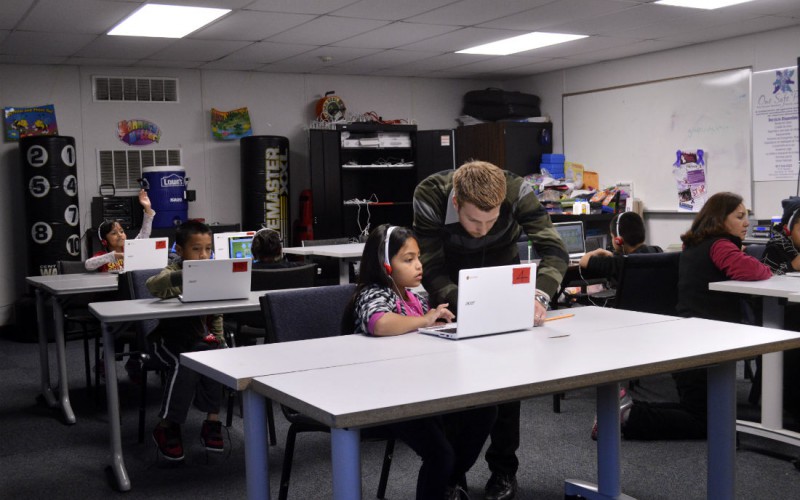

At the Grapevine Community Outreach Center, coordinator Colby Mowery helps Rocalyn Gomez with a reading program she’s using on a new touchscreen notebook. Photo/Christina Ulsh

As you head to Grapevine’s Mustang-Panther Stadium for a Friday night football game, you might not notice the two red portable buildings sitting in its shadow. But come here after school and the place is packed with kids. They come every day to practice reading, use the computer lab and work on math problems.

Brandy Salmeron and her father, Samuel, visit the Grapevine Community Outreach Center. Photo/Stella M. Chávez

Brandy Salmeron, a third grader, is one of them. Like many kids in this neighborhood, Brandy is the daughter of immigrants. Her parents came from El Salvador. They live across the street.

The neighborhood is more than 50 percent Latino, and nearly half of the families make less than $50,000 a year. Many of the kids struggle with reading and math.

Why is Brandy having trouble with math? She responds like a lot of third graders would.

“I don’t practice math.”

Dig a little deeper, though, and Brandy tosses out some not-so-simple math terms.

“Standard form. Word form. And alternate form and expanded form.”

Brandy’s making progress. And that’s the point of the Grapevine Community Outreach Center. It’s an eight-year-old partnership between the police and the school district.

The center began with the idea of lowering crime in the area and getting kids off the street. Back then, a popcorn machine sat outside to draw kids into the computer lab. Today, there are touch-screen tablets.

Home life has been tough for some of these kids, says Colby Mowery, the center’s outreach coordinator.

Colby Mowery is the coordinator of the Grapevine Community Outreach Center. Photo/Christina Ulsh

“There’s not a lot of structure in their homes or there’s not a lot of certainty,” Mowery said. “Chaos is something that they’re used to, unfortunately. And so it’s very hard for them to focus on their studies, to focus on their homework when they have to go home and they’re not sure what home is going to look like when they get there.”

Mowery and his wife moved to North Texas from Chicago last year. The job requires him to live nearby.

Mowery is fluent in Spanish. That’s helped him become something of a mentor — and earned him quite a few nicknames. Some kids call him Officer Colby.

“These are my neighbors,” he said. “These are the kids that I see walking down the street. These are the families we have dinner with. So this is my community.”

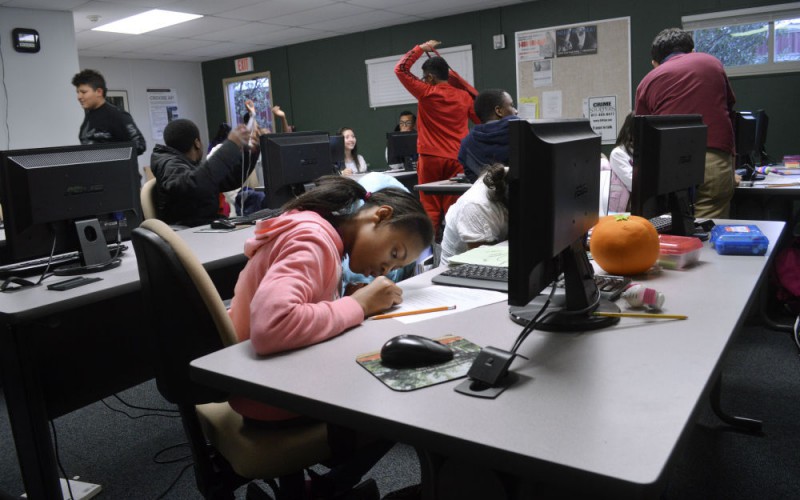

At the Grapevine Community Outreach Center, as students wait to be picked up, they play computer games. Photo/Christina Ulsh

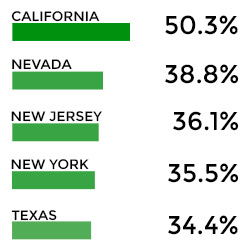

In Texas, One In Three Children Have Immigrant Parents

In 2012, about 34 percent of Texas children under the age of 18 had at least one parent who’s an immigrant. That’s according to American Community Survey data compiled by the Migration Policy Institute. That places Texas among the top five states. Hover over each state below to learn more.

Here’s a look at the states with the highest and lowest percentages of children with immigrant parents:

Sources: Migration Policy Institute; 2012 American Community Survey; KERA research

Mily Echegaray works at the Language Assessment Center in the Grapevine-Colleyville school district. She cut out a poster in honor of Brazil’s Independence Day. The center’s walls are decorated with items that celebrate the countries represented in the district. Photo/Stella M. Chávez

A one-stop place for families

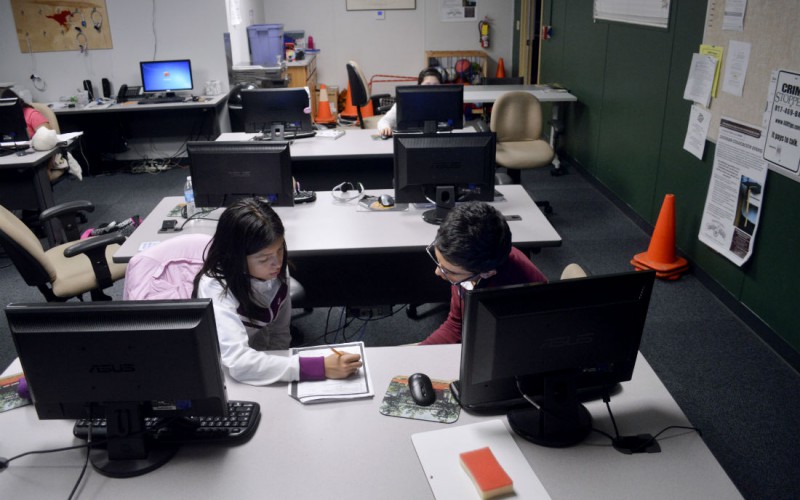

Less than a mile away from the Community Outreach Center is another portable building the school district opened over the summer. It’s called the Language Assessment Center. Kids who aren’t native English speakers get tested at the center and are then placed in the right language program.

In the last decade, Grapevine-Colleyville student enrollment declined more than 3 percent. Meanwhile, the number of students learning English — they’re called English language learners — has climbed 60 percent.

The growth among the English language learners has helped fuel the need for the assessment center, said Jodi Cox, director of world languages for the Grapevine-Colleyville district. She oversees the center.

Jodi Cox, left, is the director of world languages for the Grapevine-Colleyville school district. Zulma Arroyo is a bilingual assessment specialist. Photo/Stella M. Chávez

Many larger school districts have something similar – a one-stop place to help families that don’t speak English.

When families arrive from another country, school districts have to determine a student’s home language and explain to parents how the school system here works.

Before the Grapevine-Colleyville center opened, the small staff had to travel to other campuses to evaluate new students’ language skills. Cox said it wasn’t the best use of time, and it was challenging to track.

“There are so many other things that have to happen – vaccines, residency checks – all of those other things that often the front office staff at a campus does not have the necessary resources, specifically time or the ability to communicate in a native language, to really fully educate the parent on what their options are,” Cox said.

Evaluating language skills

“Quiero saber el nivel de ingles que tienes. Te voy decir algo de este examen …”

Laura Wernicke, a language acquisition coach, helps Javier Cabezudo with an oral exam at the Language Assessment Center in Grapevine-Colleyville ISD. Photo/Stella M. Chávez

Laura Wernicke, a language acquisition coach, talks in Spanish with 10th grader Maria Victoria Sotomayer de la Cruz. She tells her the English test she’s about to get starts out easy and gradually gets harder.

Maria isn’t like a lot of the kids here. She grew up learning English in Puerto Rico. When she’s asked to identify objects and animals, she aces it. It’s not so easy for her 17-year-old cousin, Javier Cabezudo.

“Can you repeat that?” Javier asks.

Arroyo says: “Earring is to ear as necklace is to?

“No,” Javier responds. “I know what is necklace, but I don’t know what complete that sentence.”

‘We can’t take away the struggle’

Of the students learning English in Grapevine-Colleyville, most speak Spanish. But kids also speak Korean, Urdu, Hindi, Arabic and Ukrainian.

At Bear Creek Elementary, just 5 miles south of the Language Assessment Center, students speak more than 20 languages.

“Learning a language is not easy, whether you’re 5 or whether you’re 45,” says Cox, the world languages director.

Cox stresses centers like these aren’t just there to test a student’s language skills. Many of these kids face other challenges inside and outside the classroom, from learning math to socioeconomic struggles.

“We can’t take away the struggle,” Cox says. “We can acknowledge it and support them through it and connect them with help or resources or an extra English class or a church, outreach. … We can be the people that connect those dots.”

That also means training for mom and dad – healthy cooking, exercise and parenting skills.

One recent morning at the center, the instructor puts on an exercise DVD and tells four immigrant moms to follow along.

They lift their feet and march in place. They raise their arms and move from side to side, working up a sweat.

Mily Echegaray, right, leads parents in an exercise at the Language Assessment Center. Photo/Stella M. Chávez

Marlena Castillo attended because she wants to learn more about nutrition for her family.

“Me gusto. Esta bien,” Castillo says.

She says she liked the class.

She’s originally from El Salvador and has a 14-year-old son who arrived in Texas a few months ago.

“Por que comer saludable es muy bueno,” Castillo says.

Lately, she’s been worried about her son, who’s had a difficult time adjusting to life in North Texas. He’s been eating more and putting on weight.

She left the center with some ideas to help him.

One district, many languages

Here’s a sampling of some of the languages spoken by students in Grapevine-Colleyville ISD during the 2013-14 school year:

Source: Texas Education Agency

Slideshow: Explore The Outreach Center

The Grapevine Community Outreach Center is a partnership between the police and the school district.