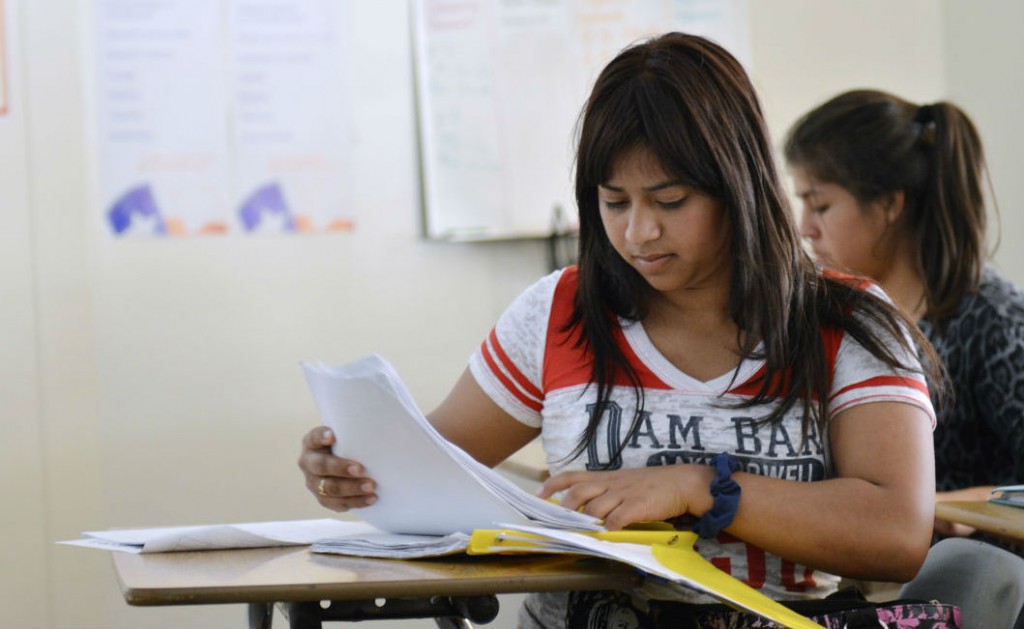

Dilcia M. Asencio Mazariegos in an ESL class in Plano. Photo/Christina Ulsh

Dilcia M. Asencio Mazariegos in an ESL class in Plano. Photo/Christina Ulsh

She Escaped Violence For A Fresh Start In Texas

Over the summer, Texas was in the spotlight for the tens of thousands of unaccompanied Central American children crossing the U.S.-Mexico border. It’s not a new phenomenon. A couple of years ago, Dilcia M. Asencio Mazariegos escaped a violent home life in Guatemala for a fresh start in North Texas. The 18-year-old is safe in Plano. But her new life in Texas is filled with challenges. She’s learning English, going to school, juggling jobs — and wondering about her future.

Dilcia M. Asencio Mazariegos organizes paperwork in an ESL class at Plano East Senior High. Photo/Christina Ulsh

Dilcia M. Asencio Mazariegos can relate to many of the Central American kids coming to Texas. In her case, she wasn’t escaping gang violence. The brutality she suffered in Guatemala came at the hand of her older brother – lashings, whacks, verbal assaults. The evidence? Scars on her back.

“My sisters have them, too,” Dilcia says, speaking in Spanish. “The truth is he hit all of us …

“Can you imagine? We have cattle and he loves the animals more than his own siblings. If something happened to one of them, he’d get angry and blame us.”

The abuse began after her dad died a few years ago. That’s when her brother, as she puts it, started acting “macho.”

To get away, Dilcia moved in with an older sister. Then her boyfriend died suddenly — he had a pulmonary embolism.

Dilcia had enough. She decided to come north.

She chose Texas so she could join relatives already living here.

Life back in Guatemala, where Dilcia M. Asencio Mazariegos is from. Photo courtesy Dilcia M. Asencio Mazariegos

An uncertain journey

On Dec. 15, 2012, Dilcia and a family member boarded a bus in her hometown of Jutiapa. They traveled through Guatemala and Mexico. Then she arrived at the U.S.-Mexico border.

“I thought I was going to have to cross the desert, but thank God I didn’t,” she said.

Instead, immigrant smugglers led her across the Rio Grande.

To stay warm during the journey, Dilcia wore pants, two long-sleeved shirts and a sweater.

She carried 20 Mexican pesos and a small purse with candy to give her energy to make the crossing.

Dilcia hopped on an inflatable raft with men covered in tattoos. They looked like they were on drugs and had been drinking. They crossed the river and entered Texas.

She and her relative joined a group of about a dozen others. Exhausted, they found a sugar cane field and slept.

On Christmas Eve, a helicopter hovered overhead and spotted the group. Border Patrol agents captured Dilcia and the others.

She was placed in a detention center. Agents told her she had to leave all her belongings behind except for the shirt, pants and shoes she was wearing. They made her remove the shoelaces.

She held onto the pesos.

Dilcia was transferred to a shelter with other kids. They were fed and clothed. Shelter workers taught them.

After about three months, a relative paid to fly Dilcia to North Texas.

Dilcia M. Asencio Mazariegos, center, holds string and takes a break with friends outside school. Photo/Christina Ulsh

‘Every sacrifice leads to a reward’

Dilcia eventually enrolled at Plano East Senior High School.

Dilcia has “learned more in these eight months than a lot of students learn in two or three years,” says Steve Crouch, an ESL teacher at Plano East Senior High. Photo/Christina Ulsh

She’s in 12th-grade English as a Second Language classes, where students are taught in English.

One November morning, Dilcia sat in her math class. The teacher handed back tests on linear graphs. Dilcia got the second-highest score. She smiled.

Students who come to the U.S. face myriad academic challenges, teachers say.

“A lot of these students don’t even have the foundation in their home language,” said Steve Crouch, one of Dilcia’s ESL teachers. “When I have them give me a writing sample in Spanish, it looks like a third grader wrote it. So I feel like I’m not just teaching English — they need to know basic language skills.”

What Dilcia lacked in education, she made up for with tenacity — in the classroom and with a tutor.

Last spring, teacher Vincent Frost used his free period to work with Dilcia and another student. Frost doesn’t speak Spanish, but with the help of Google Translate he learned about her life in Guatemala and here in North Texas.

“Dilcia – she’s incredibly sharp,” says Vincent Frost, an ESL teacher at Plano East Senior High. Photo/Christina Ulsh

“Dilcia – she’s incredibly sharp,” Frost says. “She’s a very pragmatic girl. She learns pretty quickly.”

On top of a full schedule at school, Dilcia works. In one week in November, she spent 47 hours juggling two jobs at Arby’s and Jack in the Box. Most days, she doesn’t get home till 11 p.m. Then she’s up early the next morning to get to school.

Her only time off all week? After school on Tuesdays.

“Yes, it’s difficult,” Dilcia says. “But it’s for a reason. Every sacrifice leads to a reward. I’m one of those people who believes that to have a good future, you have to work when you’re young. That way you don’t have to depend on anyone when you’re older.”

That’s a lesson from her father. And for someone with her schedule, where does homework fit in?

“I do it at night or when I’m not at work,” she says.

She spends her Tuesday afternoons away from work and with a tutor. She practices her English by texting with her sister. She checks in with her mom, who hasn’t left Guatemala.

When Dilcia M. Asencio Mazariegos isn’t in school, she works at Arby’s. Photo/Christina Ulsh

A strong work ethic

Dilcia’s work ethic doesn’t surprise Paul Zoltan, a Dallas immigration attorney who took her case free of charge on the condition she would enroll in school.

This year, he’s opened 64 juvenile immigrant cases. Most of his clients are fleeing violence. When kids like Dilcia get here, they’re willing to study and work hard.

“I’m one of those people who believes that to have a good future, you have to work when you’re young,” Dilcia M. Asencio Mazariegos says.

“She wants to be a productive member of society,” Zoltan says. “She was eager to finish her studies … in order to give back to those family members who’ve supported her. I find that admirable.”

Dilcia applied – and qualified – for Special Immigrant Juvenile Status. It’s applied in cases where a child has been abused or abandoned. For Dilcia, it was the physical abuse she suffered.

“Dilcia is one of the fortunate few to qualify for something other than asylum and it’s through that program that she’s attained residency,” Zoltan said.

Not all kids are as lucky. Some have to wait years before finding out whether they get to stay or be sent to their home country. Many of the cases get caught up in the court system.

Dilcia has a green card. She has permission to work and just got a Social Security number.

At school, Dilcia thinks she may have to repeat 12th grade. But this native Spanish speaker is making progress with her English.

“She’s trying to be independent. She has nobody to really lean on,” says Mike Fleming, an ESL teacher. Photo/Christina Ulsh

One of her teachers, Mike Fleming, worries she’s working too much. With no parents around, she has few people to lean on outside of school, aside from some relatives and her boyfriend.

“When she comes here, it’s a little bit of a safe haven,” Fleming said. “It’s kind of a social group. She can be with her friends and be kind of like a teenager. …

“I don’t get the impression she gets to do that a lot outside of school.”

A couple of weeks ago, she quit her job at Jack in the Box.

She’ll have more time – time for school, time to study. And time for sleep.

Dilcia hopes to go to college to study technology.

She’s thought about being an attorney.

“I’m good at defending myself.”

She wants to become a U.S. citizen. She wants to bring her younger brother to Texas to learn English.

She wants him to have a better life. The life she has now.

Dilcia M. Asencio Mazariegos, right, hangs out with a friend outside Plano East Senior High. Photo/Christina Ulsh

One district, many languages

Here’s a sampling of some of the languages spoken by students in Plano ISD during the 2013-14 school year:

Source: Texas Education Agency