Felicia Rush, 52, lives in a group home in Glenn Heights, Texas. She was evacuated from her home after Hurricane Harvey. (Photo/Allison V. Smith)

Felicia Rush, 52, lives in a group home in Glenn Heights, Texas. She was evacuated from her home after Hurricane Harvey. (Photo/Allison V. Smith)

For People With Disabilities, Escaping A Hurricane Means More Fear, Fewer Choices

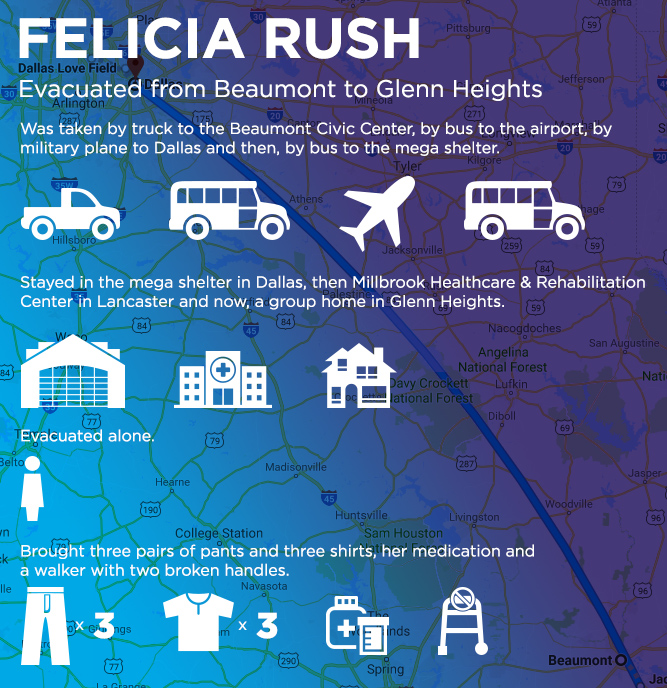

Leaving home to outrun a hurricane is nerve-wracking. Being rescued after the storm hits is traumatic. For people with disabilities, evacuation can be even more complicated. One evacuee, Felicia Rush, is trying to hold on to her independence — and start over.

Eight adults live in a five bedroom, two-story home in Glenn Heights, just 20 miles south of Dallas. It’s what’s known as a group home. Everyone who lives here has to be able to get around, shower on their own and manage their medication.

Felicia Rush, 52, has a room on the ground floor.

“I’m just glad to be living here, have extra friends to sit around and talk to,” she said. “I don’t have to be in an apartment alone by myself, and I’m glad of that.”

Felicia Rush, 52, lives in a group home in Glenn Heights, Texas. She was evacuated from her home in Beaumont after Hurricane Harvey. (Photo/Allison V. Smith)

Rush used to live alone, in a garage apartment in Beaumont. It wasn’t in great shape, and Rush has a lot of health problems. She has heart disease and diabetes as well as a bad back and bad knees. She weighs about 470 pounds, so getting up and down the stairs was a real challenge.

‘I was too afraid’

When Hurricane Harvey hit, she was terrified.

“I called 911, asked them could somebody come and help me; I was too afraid,” Rush said. “The dispatcher told me she didn’t know when the lights would come back on. So she sent the Red Cross and the police and fire department out to get me out because I was upstairs in a raggedy apartment.”

Rush had been alone in her home for two-and-a-half days before help arrived.

It was too rainy for her to walk anywhere, so she just sat in the dark, listening to her refrigerator leak.

“The smell of sewage and all that, and frogs and lizards coming through the little cracks in the house,” she said. “I was too afraid of a snake or something come up through the toilet or anything.”

She made it to the Beaumont Civic Center, with a few sets of clothes and her walker.

‘I was … hurting so bad’

Rush eventually flew to Dallas and ended up in the mega-shelter at the convention center downtown. She only stayed there for five days. She says it wasn’t a great fit for someone with disabilities.

“Us handicapped people — they had a retirement home not too far from here, they could let us go there instead of sleeping on those hard cots,” Rush said. “I was so heavy, hurting so bad I had to sit up in a chair many nights and sleep and all that, had to have people take me to the bathroom in a big wheelchair.”

Cynthia Pullen is house manager and caregiver for a group home in Glenn Heights, Texas. (Photo/Allison V. Smith)

She lived at Millbrook Healthcare and Rehabilitation in Lancaster for three months. She was well-cared for and had everything she needed — except independence.

That’s why she was so eager to move into the group home in early December. She says the caretaker supports everyone who lives there.

“Three good meals a day, and looking out for me, go to the store get extra things I may need,” Rush said. “Don’t try to rip us off. She’s giving her money buying extra things for the house and for us.”

Cynthia Pullen is that caretaker. She lives in-house, cooks all the meals, runs to the store and the pharmacy and coordinates doctor visits and physical therapy. She bought each resident three Christmas gifts, and sets her alarm every night to check on them.

“At 2, 3, 4 in the morning, checking everybody, making sure everybody is still asleep. There’s no skilled care here, it’s simply a group home,” she said.

‘Doing the best I can’

While it’s not a residential care facility, Pullen’s background is in nursing, so she knows what her residents need. For Felicia Rush to be really comfortable, it’s going to mean getting some medical gear.

“Her equipment that I need for her so very desperately is a hospital bed. A table to go across so she can eat. She needs a bedside commode that fits her body and she also needs a wheelchair,” Pullen said.

Rush has been in the group home for a month now. She’s seen a doctor, but she’s still waiting on all that medical equipment. Pullen says Rush can get around with her walker, but it’s in bad shape, so outings are out of the question.

Felicia Rush, 52, says she enjoys living with other people in her Glenn Heights, Texas, group home compared to living alone in her old garage apartment in Beaumont. (Photo/Allison V. Smith)

“It is totally torn up. She has to really watch how she walks on it or else it will crack on her,” Pullen said.

Rush is on disability, and gets about $750 a month. The group home takes 85 percent of that for room and board, so buying medical gear out of pocket isn’t really an option. She says being low-income and disabled means learning to go without.

“I just couldn’t afford a lot of things, you know, so I had to decide to let it go,” said Rush. “Just skip it, doing the best I can do with it.”

Felicia Rush still needs equipment to assist her mobility, like a power wheelchair and a walker that isn’t broken. Meanwhile, she has social interaction within her group home and receives hugs from house manager Cynthia Pullen.

(Photo/Allison V. Smith)

No Longer Alone

Rush lost her mom back in 2006 and has never really recovered. She says she put on more than 100 pounds since then. She’s bounced around the country, staying with family, moving in and out of homeless shelters.

It wasn’t a hard decision to say goodbye to that garage apartment in Beaumont. She could barely afford it. And she was lonely.

Graphic/Justin Bowers

“Bills were just running too high … and I just sat around and cried a lot,” Rush said. “Eating myself to death and all that. Couldn’t hardly get out of the house. Didn’t have nothing to do and stuff and I just wanted better.”

She thinks she may have found something better. The group home isn’t perfect — she’s still waiting on a hospital bed and power wheelchair so she can sleep soundly and leave the house. She’s not scared that she’s going to fall down the stairs, though.

Perhaps most important, she’s not alone.

“I have friends to talk to, I enjoy Miss Cynthia, I enjoy her little grandchildren coming around and speaking to me,” Rush said. “I’m glad I still have somebody here, somewhat family. I enjoy living here; I really do.”

Rush didn’t have a lot of choices when the storm forced her from her home and pushed her somewhere new. She’s grateful for the soft landing.

MORE FROM ONE CRISIS AWAY: AFTER THE FLOOD

• Harvey pushed him out of Port Arthur and onto new career possibilities

• How natural disasters challenge people of color

• After escaping flood waters, family has high hopes for the future