April Ford and her children, Jeffrey Ford Jr., 14, and Ja'Mya Ford, 12, at their home in North Richland Hills. Photo/Lara Solt

April Ford and her children, Jeffrey Ford Jr., 14, and Ja'Mya Ford, 12, at their home in North Richland Hills. Photo/Lara Solt

A Single Mother Files For Bankruptcy But Isn’t Giving Up

The North Texas economy is characterized as strong — there are lots of good-paying jobs and unemployment is low. Many working families, though, are struggling — and the debt is piling up. For some, that debt gets tougher to control as each day passes.

The Fords — April, a single mother, her 12-year-old daughter Ja’Mya and 14-year-old son, Jeffrey, Jr. — live in a cozy two-bedroom apartment in North Richland Hills.

For years, Ford worked frantically to keep a grip on growing debt. She finally decided she was out of options — and filed for bankruptcy.

Ford has been a single parent since Ja’Mya was born. She also raised two of her sister’s kids, as well as a great-niece.

“So it was four kids, me and a newborn at one time,” she says.

She was living in Louisiana then, working full-time during the school year as a preschool teacher for Head Start, a federal program that promotes school readiness among young children.

April Ford chose to file Chapter 13 bankruptcy in 2011 after falling behind financially for several summers. Photo/Lara Solt

From Full-Time Job To Financial Downturn

During the summers, Ford filed for unemployment.

“That’s when my finances really got out of hand,” she said. “I would go from making $2,500 a month to making $800 a month.”

April kept this up for several years, falling further behind each summer and wracking up debt. She had to ask family and friends for personal loans and carry a balance on her credit cards. She fell behind on her mortgage and car note, too.

She jumped at a chance for a year-round job with Head Start, even though it paid $10 an hour instead of the $14 she made before.

“I still never got caught up until maybe around income tax time,” she said. “By then, you owe your income tax out because you owe people plus all of the debt you accrued during the year.”

Ford says she thought about her finances all day, every day.

“It’s really overwhelming, like to the point where there were a lot of times that I’d just cry because I don’t know what else to do,” she said.

She just couldn’t see a way out.

In November 2011, she decided she need to file bankruptcy because she was further behind financially than she had originally thought, she said.

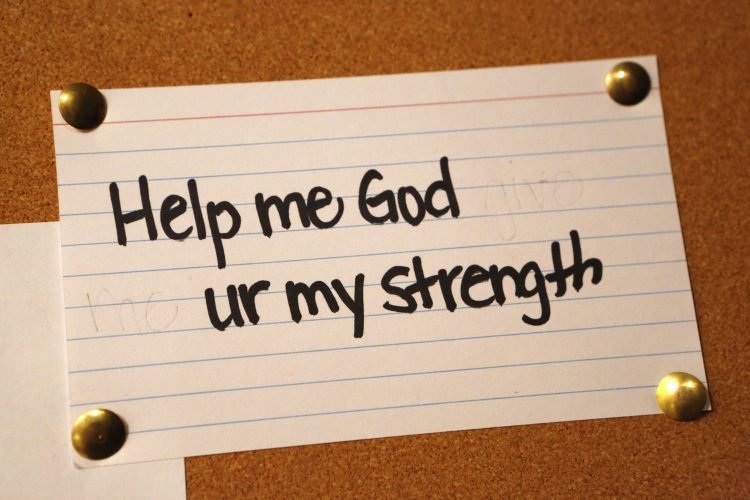

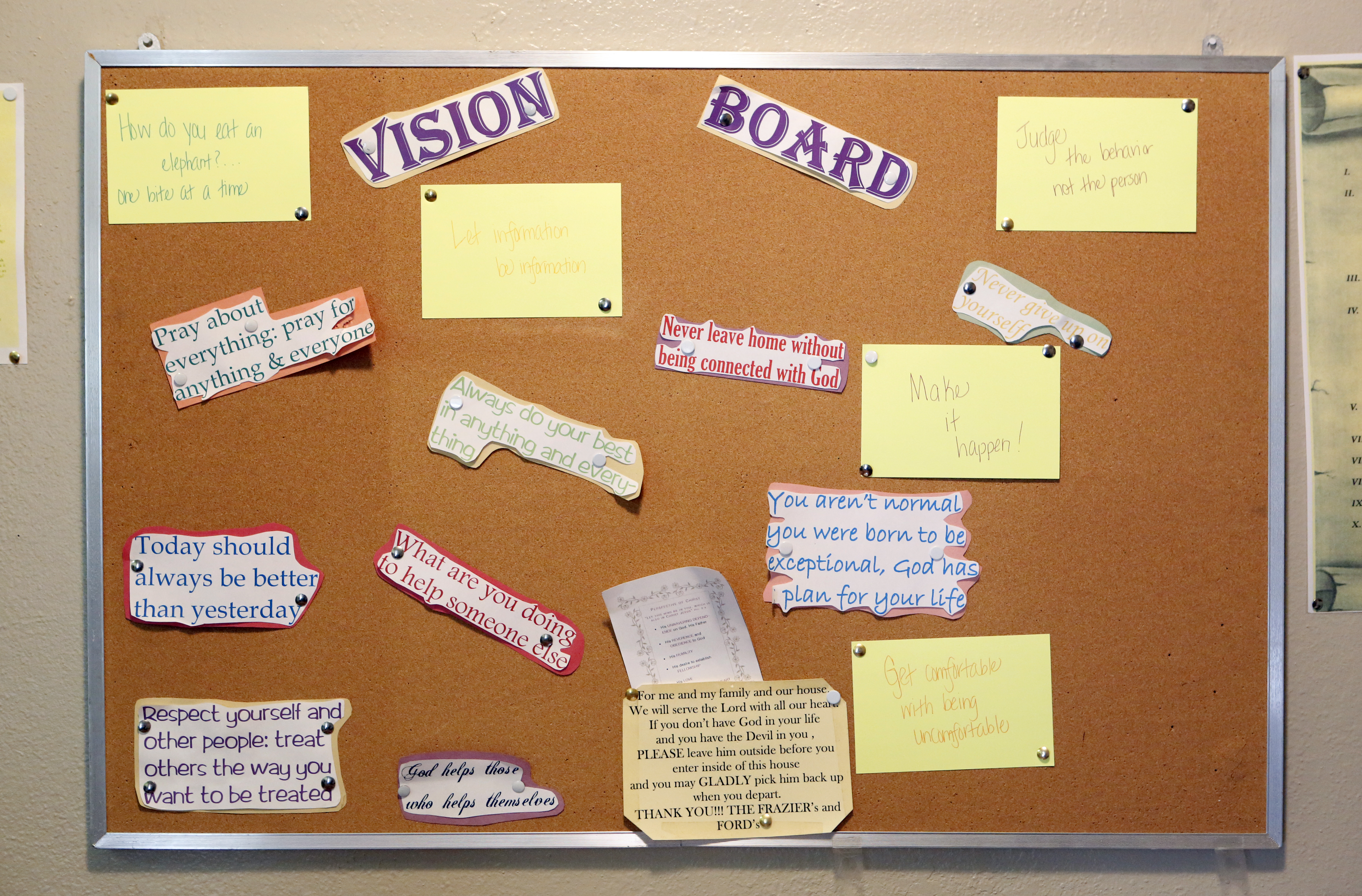

Inspirational messages are written on index cards and scraps of paper cover a vision board in April Ford’s kitchen in North Richland Hills. Photo/Lara Solt

Chapter 7 Vs. Chapter 13

Ford isn’t alone.

Between April and June of this year, more than 200,000 Americans filed for bankruptcy — either Chapter 7 or Chapter 13.

Of those 200,000 Americans, 2,700 filed in the Northern District of Texas, where Barbara Houser is chief bankruptcy judge. She explained the basics of Chapter 7 bankruptcy:

- The debtor essentially turns over all of his or her assets to the Chapter 7 trustee.

- The debtor gets to claim some of those assets as exempt.

- If your creditors and your trustee don’t object, that property is returned to you.

Folks can claim their car or house as exempt, if they continue to pay the auto loan and mortgage. Some personal property and cash can also be claimed as exempt.

Everything else is sold. The profit is divided among creditors. The rest of the debt — credit cards for example — is dismissed.

“Even through it all I still have more than some people. So, you know, I just kinda suck it up, cause what else can I do?”

WHERE THE MONEY GOES

Graphic/Molly Evans

Then there’s Chapter 13 — the path April Ford chose. Chief Judge Houser explained the structure of this type of bankruptcy:

- The debtor has an obligation to pay all of his or her disposable income to the trustee on a monthly basis.

- Disposable income is your aggregate household income minus your reasonable monthly expenses for that household. Debtors like Ford get to keep enough money to pay rent take care of bills and buy groceries.

- Chapter 13 plans last three to five years.

Most people don’t make it to the end, though. Based on her last update, Houser said the success rate of Chapter 13 plans is well under 50 percent.

The reason? Most debtors have almost nothing left each month after bankruptcy payments and expenses.

“So unfortunately a large number of debtors fall out of their Chapter 13 plan because something else adverse happens to them while they’re in the bankruptcy case itself,” Houser said.

Ford is determined not to let that happen. She’s eight months away from finishing her case. She receives financial counseling through the nonprofit Family Pathfinders in Tarrant County.

Ford brings home $2,500 each month. Half of that goes to her trustee. Then she has to pay the rent, pay her bills and buy food. By the end of the month, she’s left with about $20.

“Even through it all, I still have more than some people,” she says. “So, you know, I just kinda suck it up, cause what else can I do?”

Moving Forward After Bankruptcy

Bankruptcy stains a credit report for seven to 10 years. Ford’s credit actually rebounded in the years since she filed.

“When I first started, I was at a 530,” she said. Now she’s at 680.

The average score in the U.S. is 680. An ideal score is 720 or above.

Ford has a lot of rules for her post-bankruptcy self. When that money is freed up, she plans to pump as much as she can into savings. If she needs another car? She’ll pay cash.

Credit cards?

“Nah,” she said. “I won’t get back in that debt no more.”

Her fresh start is waiting in May of 2017— and she can’t wait to take it.